Satantango come Patantango (Tango di Pantano)

Scritto da: Paolo Meneghetti 8 dicembre 2012 in Saggi

l film Satantango, del regista ungherese Bela Tarr, fu girato nel 1994. Vi si narra il collasso d’una fattoria collettiva, ai tempi del comunismo. I pochi abitanti si lasciano andare alla vita, persa ogni speranza per un futuro migliore. A loro, resta soltanto la bottiglia d’alcol. La noia nichilistica di tutti è però improvvisamente scossa, quando si sparge la notizia che il pseudo-santone Irimias, ufficialmente dato per disperso, tornerà in paese (assieme al suo guardaspalle Petrina). Gli abitanti cominceranno a temere che dovranno andarsene. Lo spettatore può sapere che il comando di polizia zonale ha affidato ad Irimias una missione segreta. Egli chiederà ai vecchi compaesani tutti i loro risparmi, promettendo che li baratteranno con un vero lavoro (senza più l’abitudine alla puzza del bestiame, o dei campi arati). Ma sarà solo un inganno, virtualmente per lasciare che il comando di polizia distrugga la fattoria.

Satantango ha il bianconero fotografico, permettendoci di percepire la vitalità smorta dei compaesani. La sua durata al cinema è di ben 435 minuti. Una lunghezza che segue la dilatazione dello spleen esistenziale. Sembra che la gente voglia solo ubriacarsi. Ciò alla fine comporta un profondo e lungo addormentarsi. La volontà d’abbandonarsi alla frenesia della vita inevitabilmente si contraddirà. Bela Tarr usa piani-sequenza che durano 10 o persino 15 minuti. Allora, l’azione dei personaggi finisce per addormentarsi. Noi vedremo quasi esclusivamente il loro ambiente circostante. Il film vale esteticamente per la fangosità nelle relazioni sociali (costruite sulle menzogne od i sospetti), e la piovosità del destino (il quale incombe se non ferendo quantomeno appesantendo la vita, con le sue complicazioni). La desolazione delle terra ungherese è solo in piccola parte dovuta al crollo dell’utopia collettivistica.

In Satantango, lo Stato mantiene il suo potere coercitivo, grazie alla stazione di polizia zonale. I discorsi del comandante (ricevuti Irimias e Petrina) paiono chiari: “Qui tutto dipende dal mio umore… Le gente non ama la libertà, ne ha paura…” . Lo Stato, con la polizia, imporrà ancora il suo ordine sociale. Esso agirebbe paradossalmente liberando tutto il popolo, mentre ne controlla l’individualismo. E’ l’utopia del collettivismo. Esteticamente, interessa che il comandante faccia derivare il potere dal mero umore. Il film Satantango è costantemente bagnato in via percettiva. Gli umori delle persone paiono sempre umidi. Ognuno è sospettoso nei confronti degli altri: per i tradimenti sentimentali (tramite la procace signora Schmidt), o per le furberie sugli affari (specialmente, dal signor Schmidt). Lo pesudo-santone Irimias porta a compimento il destino, quando esso letteralmente precipiterà sui personaggi. Bela Tarr sceglie di non mostrarci la distruzione della fattoria. Solo, accade che gli abitanti taglino un armadietto, usando il badile. La lama precipita sul legno, come la pioggia autunnale. Nel film, muore solo l’innocente Estike. Lei è ancora una bambina, ciononostante ha già raggiunto la maturità sociale, capendo la desolazione della vita ubriacata, dentro la fattoria. Estike arriva a seviziare il suo amato gattino. E’ la percezione fangosa della vitalità. Il gattino sembra trito e ritrito nella mani di Estike, come nel campo da arare. La morte però accade in modo più rarefatto. Estike avvelena prima il gatto, e poi se stessa. La morte sopraggiunge dolcemente, senza alcuna precipitazione. Torna comunque la percezione dell’umore, in quanto il veleno va bevuto. Estike muore dolcemente, perché il destino va percepito nell’astrattezza di se stesso. L’universalità pare qualcosa che si distenda sopra i singoli enti. Il veleno si diffonderà su tutto il corpo. L’universalità del destino, nelle intenzioni del regista, andrà “bevuta” da Estike, siccome per lei “gli angeli vedono e capiscono… non c’è nulla da temere. La bambina avrebbe il dono della fede. Qualcosa che le permetta più astrattamente un bagno, sotto la pioggia battente, senza subirne il taglio (per le punte delle gocce). Nella scena iniziale, l’inquadratura rimane fissa. Un gruppo di vacche compare da lontano, uscendo dalla propria stalla. Lentamente, la macchina da presa inizia a seguirne il pascolo. La carrellata in orizzontale ambiguamente può mantenere la fissità dell’inquadratura, quando il nostro sguardo si fa parare, dai muri di più stalle.

Bela Tarr cerca un’immagine frapposta. Come le vacche scorrazzeranno per l’aia, così la nostra visione si dipanerà oltre le varie pareti. Forse Satantango va percepito nella frapposizione del destino sulla vita dell’uomo, col primo che rallenterà la seconda. La pioggia in qualche modo taglia ed appesantisce. Essa ci ostacola, e per Tarr anche a suo piacimento. Nella scena in cui gli abitanti lasciano il loro paese, il tergicristallo del loro camion gira in maniera solo disordinata (senza alcun ritmo). Il regista inquadra la luce quasi esplosivamente tramite un suo varco in profondità. Agli inizi del film, ad esempio, la comparsa dell’uomo avviene dalle nostre spalle. Sarà la prima testimonianza del continuo fronteretro chiaroscurale in cui si rallenta ogni azione individuale. Spesso i personaggi si nascondono e (paradossalmente) non si nascondono. Basta inquadrarli dalla loro schiena. Bela Tarr non nega la vitalità dei personaggi. Ma questa pare appesantita (dalla noia nichilistica). Nell’oscurità di tutti i personaggi, resta il varco d’una luce continuamente in attesa d’attrarli a sé.

C’è una scena in cui la cinepresa abbandona il nostro punto di vista per avvicinarsi alla finestra, quasi entrandovi. Ma alla fine le tendine non s’apriranno più. E’ il contraltare percettivo, in chiave ambientale, della figura umana che si muri esibendo solo la propria schiena. Nel film Satantango, l’illuminazione resta costantemente sulla soglia di sé. Gli uomini possono darsi le spalle fra di loro, appoggiandosi ai muri delle stalle, come se giocassero a nascondino (mentre spiano). Però, solo la regia proverebbe a contare il momento buono per passare all’azione. La narrazione evita sempre ogni forma di suspense. I personaggi si nasconderanno e basta. Le loro discussioni paiono inconcludenti. La stessa missione del falso profeta Irimias, agli occhi dei suoi antagonisti, sarà più il frutto d’una suggestione (innanzi al sacrificio di Estike), che non d’una coercizione. Invece, i movimenti della macchina da presa potrebbero contarsi. All’inizio del film, c’è una carrellata in orizzontale. Noi vediamo in successione le figure del vaso, del muro, della vacca e del rubinetto. La regia avanza una sorta di countdown nichilistico. Un po’ alla volta, la scenografia si spoglia della presenza antropocentrica (data dai vasi e dai muri) per diventare più naturalistica. Allora, la regia troverà l’universalità della piatta inquadratura fissa. In realtà, alla fine resta il rubinetto, che permette alla vacca di bere. La naturalità dell’acqua simbolicamente sarà già in via d’annullamento. Paradossalmente, pare che il rubinetto strozzi la vitalità della vacca, incombendo su questa. L’acqua sarà appesantita non solo dal più naturale diluvio, ma pure nell’antropocentrismo della sua canalizzazione. Frequentemente, il film mostra che i personaggi si lavano entro una piccola bacinella. Non ci pare una scelta praticissima. Sembra difficile lavarsi bene in così poco spazio. La bacinella sarebbe il contraltare artificiale della più naturale pozzanghera. Mancando una vera e propria immersione nell’acqua (dalla vasca), il corpo nudo si comporterebbe come il fango, che subito appesantisce il bagnato.

Nel film Satantango, la regia ci aiuta a percepire i movimenti virtualmente piovosi della vitalità umana. Bela Tarr cercherà un’inquadratura che scandisca il compiersi del destino avverso ai compaesani. C’è una scena in cui noi vediamo prima il braccio d’un uomo, e poi un bicchiere sul tavolo. La cinepresa si sposta lentamente, in orizzontale. Il braccio si distende, e la mano prenderà il bicchiere. E’ il momento in cui l’uomo vuole bere. In seguito, il braccio si distende in direzione opposta, rimettendo il bicchiere sul tavolo. La scena si ripeterà ancora. L’inquadratura si percepirà in via pendolare. Ma è un countdown che, per l’appunto, non porta a nulla, lasciando che il personaggio del bevitore semplicemente s’addormenti. Il braccio, incurvato per prendere il bicchiere, avrà la stessa configurazione del rubinetto per le vacche. Ciò conferma la percezione estetica che la vitalità si faccia strozzare. Il film Satantango è interamente costruito sull’inerzia narrativa. La stessa missione di Irimias accade solo astrattamente. Il rubinetto strozza la vitalità della vacca, ed il braccio che prende il bicchiere (col vino al posto dell’acqua) quella dell’ubriacone.

Il film Satantango va percepito nella continua frapposizione degli elementi scenografici. La visione del rubinetto taglierà quella della vacca, la visione del braccio taglierà quella del bicchiere, magari nell’alternanza di se stesse (quando la macchina da presa si sposti da sinistra a destra, o viceversa). Non c’è alcuna flessibilità percettiva. Ove l’inquadratura si faccia binaria, il primo elemento parrà semplicemente spalmato sul secondo, nella solita pesantezza della loro fangosità. Anche per questo, uno dei personaggi si lamenta del suo spleen esistenziale dichiarando: “La flessibilità è ciò che ho perso”. Nella scena più famosa del film, Bela Tarr usa un piano-sequenza di 15 minuti. L’illusione che l’alcol rivitalizzi fermenta sul ballo dei compaesani, al bar. In realtà, malinconicamente noi percepiamo che loro si lascino andare al solo addormentarsi. Là, manca completamente ogni flessibilità coreografica. I compaesani si limitano ad allargare le braccia, così da spalmare la fermentazione dell’alcol.

http://www.cinefilos.it/saggi/satantango-come-patantango-tango-di-pantano-39507

Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó

July 4, 2013 by Eric McDowell in Blog

What can you do in eight hours? Work a full day’s work or log a solid night’s sleep. Run 60 eight-minute miles—that’s over two marathons—or microwave 240 Hot Pockets. Or watch Sátántangó.

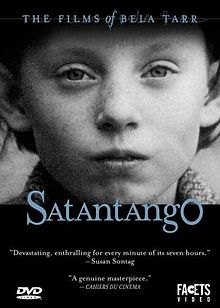

I recently set aside a whole Sunday to watch the film critics consider to be Hungarian director Béla Tarr’s masterpiece. Filmed between 1990 and 1994—delayed in part because political antipathy toward his previous effort, Almanac of Fall, had put Tarr in “really deep shit”—Sátántangó actually runs 435 black and white minutes, closer to seven and a half than eight hours. Still, when you account for changing out the DVD set’s three discs, which for me involved shooing the cat off of the plastic case, not to mention stretching, bathroom, and eating breaks, you’re looking at an all day experience, a test, many viewers agree, of cinematic endurance.

I first came to Béla Tarr through the literary critic James Wood, whose New Yorker piece on the writer László Krasznahorkai, Tarr’s close and frequent collaborator, appealed to my interest in the extreme, the obscure, the difficult. Not long after I read Krasznahorkai’s Melancholy of Resistance, packed in dense type with sentences too long to quote, paragraphs too long to read in a sitting, I got a hold of Tarr’s beautiful film adaptation, called Werckmeister Harmonies after one of the novel’s central sections. But all the buzz on the online forums was about Sátántangó.

I decided to read Krasznahorkai’s Sátántangó before watching Tarr’s. Though the novel, the author’s first, was originally published in Hungary in 1985, it became available to English readers only last year via New Directions’ handsomely bound hardcover edition of George Szirtes’s translation. I finished the novel the night before my chosen viewing date; for what it’s worth, the film proved to be fairly loyal to the book, both in terms of mood—grim and darkly funny—and narrative shape. The “story,” an aspect of filmmaking secondary in Tarr’s estimation to image, sound, and emotion (“I don’t care about stories. I never did. Every story is the same…. The stories are just covering something.”), involves the return or “resurrection” of two men thought dead to a derelict farm estate. After the body of a local young girl (Erika Bók) turns up, the messiah-figure Irimiás (Mihály Vig) offers a frank but seemingly empathetic appraisal of the estate’s depleted and dejected community; then, with the help of his sidekick Petrina (Putyi Horváth), he convinces the hangers-on that if they give him their pooled savings, he will arrange a better future for them… Structurally, the film retains the novel’s organizing “tango”: six steps (chapters) forward, six steps back. Shifts in perspective create overlaps or folds in the chronology, so that, for example, in one scene we see the eponymous dance from the not-yet-dead little girl’s point of view, and then again in another from the point of view of carousers themselves.

This latter scene, which you can watch here, demonstrates a few of the characteristics typical of Tarr’s work. First, the long take. In “Talking About Tarr,” a symposium transcribed in the Sátántangó DVD booklet, moderator Susan Doll compares an average Hollywood film’s “1,100 shots per 100 minutes” to the 39 shots that make up Werckmeister Harmonies’ 145 minutes. That’s an average shot length of 5.5 seconds vs. almost four minutes! Over Sátántangó’s 435 minutes there are something like 172 shots, averaging 152 seconds or about two and a half minutes per shot. This stylistic habit is so common in Tarr’s films that one interviewer begins his question about it, “You’re probably sick of being asked about the long takes in your films…”—to which Tarr responds: “Yes, I’m getting mad about it. I’ve answered it a thousand times.”

The dance scene begins with a single five-minute take, cuts to show the girl watching at the window, then cuts back to the dancers for another five minutes. The power of the scene’s long takes, their tension, comes not so much from narrative suspense (“What will happen?”) as from suspense of another kind—“How long can this go on?” or even the more abstract “Why does Tarr want me to watch a room of wasted people dance for so long?” Of course the first question is more easily answered than the second. Tarr gets tension too from that looping, infectious accordion music, which I found myself humming the next day, or the way the distance and duration of the shot gives the scene space for both repetition and variation—the steps of the dancers, the stumbling of the drunks, the tireless tapping of the bartender and the man with the cane. Containing all this in one frame occasions a kind of elegant chaos.

Despite Tarr’s reluctance to answer the same old question, he does offer a useful observation about his long takes: they provide “a special tension between the actors and the camera. That’s why I like it.” I’ve heard the Steadicam work in The Shining described as “prowling,” and though Tarr is up to something different from Kubrick, we do get the sense in Tarr’s films that the camera has a consciousness of its own. The meditative tracking, panning, and zooming in this scene contrasts with the frenzied action in the bar; this action doesn’t necessarily dictate the attention of the camera. We might even think of the consciousness of the camera as the primary or controlling consciousness of the scene. (For another look at this technique, watch for the way in this scene, around the 0:50 mark, the camera lingers a few extra seconds, not ready to relinquish its station, after the subject has left the frame.)

A final trait of Tarr’s work that’s well represented in the dance scene is the same complex mixing of gravity and comedy that we find in the film’s title: both Satan and tango. “All my movies are comedies!” Tarr has said (“Except The Turin Horse,” his latest and supposedly final film). The incongruity is obvious, for instance, when we put the quarrelsome man in the leather jacket next to the gentle one who paces with a breadstick balanced on his forehead. (Later we see a man and a woman laboriously chewing toward each other’s lips from opposite ends of a breadstick.) But in another way, for me the actions of just about every character in the bar vacillate between lightness and darkness, from cheer to desperation; the long take accommodates this kind of range, too.

What’s it like watching an eight-hour movie on the couch in your apartment? It doesn’t “feel” as long as you might expect, I think, because something happens to your sense of time and scale. Of his 1988 film Damnation, Tarr says: “…if you’re a Hollywood studio professional, you could tell this story in 20 minutes.” The same thing, relatively, could be said about Sátántangó. Another director might cut the minutes-long opening tracking shot, starring a slow gang of lowing cows, to a more commercial 5.5 seconds. After all, what does it add to the “story”? But “[w]hy did I take so long?” Tarr muses. “Because I didn’t want to show you the story.” He’s interested, rather, in showing lives—of people, of places. Which may be why he paces his films closer to “real time.” What happens, I think, if we make ourselves available to this rejection of our usual moviegoing expectations, is that we become invested in the lives we’re witnessing. The more urgent they become, the faster time seems to move, and before you know it, you’re changing discs.

Not to say that my mind didn’t wander while I watched Sátántangó, that I didn’t undergo occasional fits of frustration or bouts of shame-inducing boredom (though what’s wrong with a little boredom if it expands the range of emotions you encounter in a single artistic experience?). Tarr is a difficult, challenging artist, and the question of accessibility is crucial in thinking about his work. Even on the most basic level, catching the opportunity simply to see Sátántangó can be a feat. Not long ago, copies of the film were hard to come by, and even now, after the 2008 Facets Multi-Media release of the DVD box, purchasing the film will run you at least $50. Good luck catching a screening outside of New York or other big-city centers of culture (online forums are filled with hopeful but often unanswered inquiries as to local screenings). Doubtless there’s a financial issue involved: to watch these films about penniless Hungarian villagers, it helps to have money. Without my subscription to The New Yorker, I might never have heard of Béla Tarr; the only reason Sátántangó was so easy for me to decide to watch and get a hold of was because I have access to an incredible university media library just a mile from my apartment.

But when you think about it, that’s something you can’t say about most movies—you really have to decide to watch Sátántangó. You won’t find it on TV; you wouldn’t be likely to stream it on a whim, even if it were available on Netflix instant. You have to sniff it out, find a copy, and make time, lots of it. Then tackle the intellectual demands Tarr makes on his viewers. The running-time of Sátántangó is an obvious turn-off—who wants to spend eight hours of their day watching a movie? Who can? Not to mention a black and white one, one with spare, subtitled dialogue, and a deliberate eschewal of plot. Some viewers suspect that the main draw of the film actually is the running-time—watch it to join the elite club—and blame it for helping give foreign films the reputation of being esoteric and boring. Others congratulate it for flipping the “friendly foreign film” the bird. Tarr himself takes something of an anti-intellectual approach: “Don’t be too sophisticated. Just listen to your heart and trust your eyes.” Whether you can find a screening (which Tarr insists is the appropriate way to view his films) or borrow a copy, I suspect if you watch Sátántangó, you’ll walk away eight hours later at the least admiring the director’s complete and unflinching commitment, whatever anyone else says or does, to his singular vision. Just don’t watch it on your cell phone, which apparently Tarr has heard of someone doing. “That hurt me,” he says.

http://www.michiganquarterlyreview.com/2013/07/bela-tarrs-satantango/