In un paese indefinito sull’orlo del precipizio giunge dal nulla un misterioso nano detto il Principe insieme ad un enorme container contenente una balena imbalsamata.

Dalle fisarmoniche sfiatate di un assurdo tango ballato col gomito alzato in una locanda ai confini dell’universo, Tarr ci trasporta nuovamente in un altro non-luogo riallacciando il filo col suo Capolavoro Satantango (1994). Siamo ancora in un locale dove uomini derelitti si trascinano a fatica tra tavoli e bicchieri sporchi, entra in scena il giovane János Valuska che atteso dai clienti fa veder loro che cosa sia un’eclissi solare. E dopo che la sua rappresentazione ha fine, parte la prima di quelle che saranno in totale 4 entrate musicali, strepitose emozionanti palpitanti, del fedele Mihály Víg. Ed è da questo piano sequenza iniziale che si può comprendere, o almeno provare a farlo, su quali mondi di idee si affacci questo film, su quali abissi universali getti il suo sguardo penetrante.

Nell’osteria vediamo la solita decadenza tarriana, il solito ammasso di rifiuti umani, ubriaconi li definirà il barista. Quando Valuska profetizza l’oscuramento del sole con le sue descrizioni di terrore e miseria, ecco che parte una musica in antitesi con la materialità che si consuma sullo schermo. Come il musicista tedesco Andréas Werckmeister che considerava la musica al pari dell’armonico movimento degli astri ma che fu “falsificata” proprio dallo stesso tramite il suo sistema in ottave, Tarr suggerisce che non c’è equilibrio negli uomini, non c’è l’armonia delle note fra le persone che come goffi pianeti s’incastrano tra loro. La musica continuerà a suonare anche mentre János cammina nella strada deserta fino a scomparire nel buio. C’è solo lei, gli esseri umani non ce l’hanno fatta.

La seconda entrata musicale avviene con l’ingresso di Valuska nel container. Si ripete il contrasto: fuori gruppetti di uomini minacciosi, dentro l’innocente ragazzo a tu per tu con l’essere mastodontico. È difficile dire cosa sia la balena, ma qualcosa mi invita a credere che il corpo offeso dalle cicatrici e il suo occhio esangue siano i sintomi di ciò che gli uomini fanno e hanno fatto con le loro ingiustizie. La balena è un dio martoriato, la carcassa di ciò in cui si credeva e che è stato tradito per seguire la voce di un nano. I riferimenti all’olocausto non sono poi troppo lontani: una popolazione allo sbando, l’assenza di valori, il sopruso che avanza inesorabile. Gli elementi ci sono tutti, insieme a quella musica meravigliosa che si staglia nettamente sulle bassezze della Storia.

La terza apertura è la più dirompente. Anticipata da una lunga marcia ordinata di uomini che sembrano realmente dei soldati, alla quale seguirà la devastante irruzione nell’ospedale che rappresenta uno dei momenti di cinema più crudi da molti anni a questa parte in cui vi è chiaramente un gigantesco vuoto armonico fatto di calci ai ricoverati, mobili e letti fracassati, ecco che dietro una tenda la mdp svela un vecchio uomo nudo, scheletrico, immobile.

In quell’istante la melodia comincia, altissima, sale nei cerchi concentrici del cielo fino ad accarezzare i pianeti solitari le comete scie dorate fra satelliti instancabili, e il cuore, il nostro cuore si frantuma.

L’immagine dell’anziano nudo e indifeso di fronte al male degli uomini ha un potere talmente annichilente da metter ancora di più in risalto la melodia celestiale in sottofondo. E a concludere magistralmente questa indimenticabile sequenza ci pensa il primo piano spaventato di Valuska che nascosto nell’ombra aveva visto tutto. Anche un sognatore come lui sta per arrendersi.

Il quarto ingresso arriva inesorabilmente alla fine. Quando ormai tutto è stato distrutto, tutto. È distrutto l’entusiasmo di János ridotto ad un automa su una barella, è distrutto il container che proteggeva la balena lasciandola ancora più sola di quel che era nella piazza centrale alla mercé di chiunque. La struggente armonia parte da qui, con l’intellettuale Eszter, convinto detrattore di Werckmeister, che si avvicina pian piano alla solitaria balena in mezzo ai detriti. La guarda nell’occhio spento eppure così compassionevole, colmo di pena per quegli esseri umani che l’hanno strappata dal suo mondo per portarla in un regno di scheletri e macerie. In cui non c’è grazia, non c’è logica, non c’è dolcezza, non c’è musicalità.

Nel momento in cui Eszter esce di scena una nebbia sottile fa scomparire la carcassa dell’animale. L’eclissi su questo (sul nostro?) popolo è giunta, il buio è così arrivato. Non ci sarà lo spiraglio di luce sperato da Valuska, resterà solo la musica nei titoli di coda. Libera da qualunque Werckmeister, e infinitamente sopra di noi.

http://pensieriframmentati.blogspot.it/2010/04/le-armonie-di-werckmeister.html

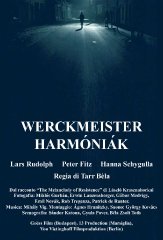

“Werckmeister harmóniák” di Béla Tarr

– venerdì 4 giugno 2010

Per la consueta rubrica di cinema, voglio parlare di un regista a mio avviso imprenscindibile nel panorama europeo contemporaneo, poco noto ai più, ma molto amato tra critici e cinéphiles.

Béla Tarr, classe 1955, ungherese di Pécs, da anni persegue l’ideale di un cinema alternativo ai prodotti di largo consumo.

E lo fa scardinando tutte le regole base di ciò che il mercato oggi per lo più propone, e cioè:

- evitando le trame semplici e prevedibili od eccessivamente bizzarre ed arzigogolate di molte supposte “pellicole originali”;

- evitando l’utilizzo di dialoghi e linguaggi eccessivamente banali ed elementari (talora anzi si dilunga in citazioni poetiche);

- evitando di ingaggiare attori famosi o presunti tali, la cui capacità di recitazione è spesso inversamente proporzionale all’aspetto fisico; e anzi privilegiando gli sguardi duri, brutti ma espressivi di intepreti sconosciuti ai più;

- evitando l’utilizzo smodato di effetti speciali per inebriare lo spettatore, se non se ne sente l’esigenza;

- utilizzando una fotografia in bianco e nero, fatta più di neri che di luci, più di nascosti che di evidenze, più di naturalezza che di artificiosità;

- evitando tassativamente quella regia da videoclip per la quale lo spettatore rimane colpito più dalla velocità e sequenzialità delle scene che non dalla cura delle stesse; prendendosi dunque tutto il tempo necessario alla costruzione di riprese estremamente lunghe e complicate.

Stanti tali premesse, l’obiettivo del presente articolo è facilmente desumibile: è possibile trovare (ed è auspicabile cercare) una tipologia di film che abbiano maggiore spessore intellettuale di quelli che vanno per la maggiore.

“Le Armonie di Werckmeister” terza opera del succitato Béla Tarr, è sicuramente una delle possibilità da prendere in considerazione.

In questo lavoro si concentra infatti tutta la poetica precedente del regista (che, ricordiamolo, è autore anche di “Satantango”, dell’epica durata di 7 ore e mezza), e si esplicita attraverso 39 -bellissimi- piani sequenza per una durata complessiva di 145 minuti.

All’interno di questi “long-takes” la macchina da presa si distingue per eccellenza e maestria, riprendendo avvenimenti complessi e frastorna(n)ti con un’abilità tecnica ed una consapevolezza che ha pochi eguali nella storia del cinema (vedi alle voci “Orson Welles”, “Stanley Kubrick” o “Alfred Hitchcock”).

La trama in breve: in una piccola città di provincia ungherese giunge un piccolo circo che ha due uniche attrazioni: un’enorme balena imbalsamata e un misterioso nano chiamato “il Principe”.

Nella solitudine del suo studio György Eszter studia una teoria musicale che vuole sovvertire l’ordine armonico stabilito nel ’700 da Andreas Werckmeister.

János Valuska, il ragazzo che consegna i giornali, fa la spola tra lo studio del musicista e la piazza del mercato dove il Principe incita i frustrati e poveri abitanti alla distruzione di tutto.

Una notte la furia divampa e qualcuno ne approfitta per prendere il potere.

Detta così, e di fronte all’universalità anche politica di una trama che tange sia i percorsi esistenziali che le emozioni più profonde dell’uomo, ci si ritrova a condividere con il regista sia la tematica del progressivo imbarbarimento dei rapporti interpersonali che l’inevitabile consapevolezza, come cittadini, della propria “riduzione in schiavitù”: temi quanto mai portanti dei nostri tempi (ed il film è del 2000).

L’autore non lesina nel rappresentare l’”hobbesiana” sopraffazione dell’uomo sull’uomo, ma la violenza che ne scaturisce è quasi catartica: non a caso una delle scene madri della pellicola è costruita come una sequenza a la “Metropolis” di Fritz Lang.

Ed è direttamente a noi spettatori che egli si rivolge quando tocca punte di lirismo visivo che letteralmente spiazzano, costringendoci a riflettere sull’insensatezza delle nostre azioni. Non è un’opera a tesi, ma è impossibile non cogliervi un riferimento universalistico.

Un decennio cinematografico che produce un capolavoro come questo è un decennio che merita di essere vissuto.

P.S. Consiglio ai (potenziali) spettatori: se la sequenza iniziale non vi cattura sospendete senza remore la visione, non vi si confà.

http://www.laruotagruaro.it/terza_pagina/film/werckmeister-harmoniak-di-bela-tarr

How to Watch Werckmeister Harmonies

[You can now download a version of this post as a podcast here.]

First of all a disclaimer. Despite the title of this post, I don’t want to suggest that what follows is a “correct” reading of Béla Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), or to foreclose individual responses to it: it’s an enigmatic film, and no critical commentary can seal it up or explain it away. I’ve put it on an introductory film module for my second-year students and, while I myself perceive greatness in it, I understand why many viewers, thrown into a screening room on a Monday morning, might find it a bit of a struggle, so I want to give a few preparatory remarks that might give them a way in to its marvels, or at least to its workings: students don’t have the same options as regular cinemagoers – they can’t just walk out if they find it dull, dour, opaque and frustrating, because they know I’ll be asking them questions about it and expecting some considered responses. You don’t have to like this film, you just have to think about it, but I hope that it can be more than an intellectual exercise, but rather an emotionally enveloping experience.

Why does it have a reputation as a difficult film? Well, it’s quite long, slow, and it doesn’t tell its story in a familiar way. Rather than subsuming all of the stylistic and formal elements of the film to the all important narrative, Tarr’s camera will often linger on incidental details and minor characters, and it isn’t always clear what relevance they have to the film. Sometimes he will hold a shot for longer than seems necessary – but that just assumes that the length of a shot is “necessarily” defined by its function as a unit of narrative information. Tarr’s shots sometimes go on for so long that you have time to concentrate on their other aspects. Some people find this style to be ponderously slow and boring, a failure to get to the point and tell the story succinctly. You can approach the film from this angle, comparing and contrasting it with Classical narrative cinema, films that economise on their shot lengths and deliver the narrative in a series of swift, contained scenes. Alternatively, you can consider Werckmeister Harmonies on its own terms, and suspend the expectations that you usually bring to the cinema. Once you stop expecting the story to unfold at customary, commercial speed, it should make a lot more sense: shots will last long enough for you to appreciate their graphic elements, their composition, their ritualistic build up to a crescendo or anti-climax, and you can take in the scenery: every shot is composed in a stately manner, and the speed of the tracking rarely changes. Even sequences of violence and destruction do not deflect the camera from its steady movement through space.

I can summarise the plot quite quickly: in an unnamed Hungarian town, a circus act arrives, consisting of a giant whale and special guest ‘The Prince’. With it comes an ever-increasing, indefinable sense of impending disaster, as if it exerts a hidden power over the townsfolk and eventually compels them to a futile, destructive uprising. One man, János Valuska, observes the mounting tension as the whale attracts people from neighbouring towns, while others seek to take advantage of the situation to attempt a seizure of power: Tünde Eszter blackmails her estranged husband György into using his influence to gain support for her plot to restore “order and cleanliness” to the town, and János finds himself a helpless outsider to the ensuing chaos.

With its underlying aura of evil, social dissolution and masses motivated by abstract forces, it seems obvious to ascribe to the film a political allegory. After World War II, Hungary had been made a Communist state, ruled remotely by the Soviet Union, who maintained a military presence and enforced Stalinist principles of collectivisation. Following a popular revolt in 1956 against the repressive regime of Communist leader Mátyás Rákosi (which the Soviet Union put down with brutal military force), Hungarian socialism developed as a mixed ideology, a greatly liberalised approach to communism that held fast until 1989, when the collapse of communist control in Central Europe allowed a shift to a democratic government and a capitalistic market economy. If we see this as a film set at the close of one enveloping political ideology but prior to the establishment of another, it might be easy to find parallels in its depiction of an aimless populace primed for orders by a charismatic demagogue. But it might not be that easy to map an allegory onto the history. As Jonathan Romney suggests:

The film is dominated by a brooding atmosphere of apocalyptic unrest, though it is implied that the cosmic ‘evil’ pervading the town is the product of bourgeois paranoia. Tempting as it may be to relate the story to political changes in Hungary in the last days of Communism (Krasznahorkai’s novel was published in 1989), Tarr has insisted that his films contain no allegory. Yet the narrative is certainly one of anxiety about the breakdown of an old, enfeebled order and the explosive release of repressed popular energies.

It’s not easy to pin down such an allegory, even if we want to impose one, because the causes of the rising violence in the town are not easily identifiable. As Romney continues:

From the very start rumours are rife about the universal disruption heralded by the anticipated eclipse. But is any of it really caused by the arrival of the whale, or is the huge dead creature, with its glassy eye, simply the impotent witness to human destructiveness? Is the supposedly demonic demagogue Prince anything more than an impotent, robotic-voiced homunculus? The one truly identifiable centre of malevolence is Tünde, a reactionary opportunist exploiting superstition to gain power in the name of order. It may even be that her musicologist ex-husband Eszter, obsessed with the theories of 17th-century German composer Werckmeister, has himself contributed to disturbing the harmonic order of things by withdrawing from any active involvement; at the very least he is a representative of an enfeebled intelligentsia, vainly fiddling with abstractions while the world burns.

Tünde is having an affair with the chief of police, a stupefied, gun-waving drunk whose children we see enacting a disturbing scene of gleeful dictatorship: probably too much even for Supernanny, these two don’t just refuse to go to bed; they threaten Janos with violent reprisals if he interrupts their bed-bouncing, militaristic reverie. So, Tarr subtly indicates the connections between characters without trumpeting their symbolic function or their direct influence over events. Most elusive of all is the Prince, a phantomic presence who is never directly seen onscreen. We are told that his speeches are inciting the population to acts of rebellious vandalism, but we only hear him once, seeing a pictorial silhouette of his face cast in shadow on a wall as he spouts what sound like vague, pre-programmed slogans.

Nevertheless, András Bálint Kovács has made a very convincing attempt at outlining the socio-political significance of Tarr’s recent films:

The significance of Béla Tarr’s films in the 1990s—beyond their stylistic and aesthetic values—is that they offer the most powerful and complex vision of the historical situation in the Eastern European region over the last decade. His films reach but few viewers; still, it would be hard to deny that he speaks for hundreds of millions of ordinary European people in his universal and ruthless language, people who feel cheated and disappointed for wasting all the values of their previous lives in a matter of seconds, who fall prey to petty intrigues, who are led by petty, mean promise-mongers that talk of high ideals but follow their selfish power and financial interests. This feeling is born not only from the past, but also from the present experience; although the setting and certain characters may have changed, the same petty fights and intrigue still rule our lives; other ideologies are quoted, while the misery remains or even deteriorates in the former Soviet Union, Romania, or Yugoslavia. We cannot trust anyone; we cannot believe in anything, for all high ideals are but tools to abuse the helpless. We, Eastern-Europeans, are the tenants of the blocks of flats in Satantango and we desperately cling to all the promises of the promise-mongers who only take our money. We are the hopeless drunkards; our leaders are the alcoholic policeman, the clever smuggler, and the mafia-man inn-keeper. And we are Valushka, as well, who serves all above him with endless humility and looks the whale in the eye with terror, hoping for Mother Nature’s help. And we are the mob, too. In our helplessness we would like to break the windows of all luxury shops where they sell articles, of which we can only dream, and we would like to turn our anger against those who are even weaker and more helpless. All of this, of course, is an exaggeration—the exaggeration of great art.

Perhaps we can ask the director himself for his opinion on all this. Does he have any comments on what this film is about? Is it a metaphysical excursus on the nature of being?:

I just wanted to make a movie about this guy who is walking up and down the village and has seen this whale. And, you know when we are working we don’t talk about any theoretical things. We only ever have practical problems. And it’s the same with the writer. Mostly we just talk about life. How it’s going on the street. We never talk about theoretical things. We never talk about Chaos or existential things. We just talk about someone coming into the room and he wants something and the other guy who is sitting there doesn’t want these things. That’s all.

Thanks. That helps. Care to elaborate on the cosmic significance of your work, which many critics have tried to ascribe to it?

You know how it happens, when we started we had a big social responsibility which I think still exists now. And back then I thought “Okay, we have some social problems in this political system – maybe we’ll just deal with the social question.” And afterwards when we made a second movie and a third we knew better that there are not only social problems. We have some ontological problems and now I think a whole pile of shit is coming from the cosmos. And there’s the reason. You know how we open out step by step, film by film. It’s very difficult to speak about the metaphysical and that. No. It’s just always listening to life. And we are thinking about what is happening around us. […] I just think about the quality of human life and when I say ‘shit’ I think I’m very close to it. […] Everything is much bigger than us. I think the human is just a little part of the cosmos.

And what about the diffuse forces of evil that seem to lurk in this film? Does that come from the cosmos?

No. I think human responsibility is great, enormous. Maybe the biggest factor. You know, I don’t believe in God. This is my problem. If I think about God, okay, he has a responsibility for the whole thing, but I don’t know. You know, if you listen to any Mass, it looks like two dogs when they are starting to fight. And always, I just try to think about what is happening now.

[The above quotations come from an interview with Béla Tarr conducted by Fergus Daly and Maximilian Le Cain in 2001. I take no credit for asking those questions. You can read more of it here.]

I’m not sure that makes things much clearer. In other interviews, Tarr is more accommodating, as when he gave Eric Schlosser his summative aspirations for Werckmeister Harmonies:

I have a hope, if you watch this film and you understand something about our life, about what is happening in middle Europe, how we are living there, in a kind of edge of the world. That’s all. After you see the film, I think you know a bit better.

Tarr is fascinated by everyday details, the grooves, wrinkles and stubble of cold, sour faces and the roughness of every surface, but he doesn’t do this naturalistically or in the service of any other form of social realism. At least not entirely. The lengthy tracking shot of János walking through the town square, between the silent, hangdog faces of the men standing around reveals many expressions in turn, granting each an individuality that belies their position as part of an accumulating mass. They remain almost entirely voiceless throughout their progression from bystanders to destroyers, in contrast to the Prince, who remains a disembodied voice throughout the same period. We see the locations in a palpable, unvarnished form, and this provides a kind of insight into life in “middle Europe”, but those naturalistic elements are folded into an ineffable sense of something larger or something less concrete.

In another interview Tarr confirms his realist focus by once more refuting the allegorical complexity of his work and insisting that the film speaks for itself through its surface syntax:

If you are listening to the film, and simply watching, you will find there is little reason for speculation about the film’s meaning. This is why I have said: No allegories, no metaphors, no symbols, nothing…

It seems extraordinary for Tarr to claim that there is no higher purpose to his film, and I can’t help thinking that he relishes playing games with us. He must know that his films are enigmatic, never obvious in their storytelling. The lesson here may be that the director’s statements about a film, even the director’s intentions while making it, are not necessarily the most helpful pieces of information. Ultimately, you are alone with the film, and you will find things in it that might not occur to the person sitting next to you in the darkness. Even if Tarr might deny any intended allegory or metaphysics, many viewers seem to bring the weight of those ideas to the films for themselves, as if they, like János, are gazing at something that meets their gaze and holds it.

Let’s talk about shot length. The plot outlined above might sound like a great opportunity for a political thriller, with spies and intrigue and betrayal and riots, but Tarr slows the proceedings right down and allows the story to seep out of the setting and the characters rather than manouevring them into a tight sequence of storytelling elements. This is all signalled in the opening shot, a ten minute mini-masterpiece in which János uses the assembled downtrodden drinkers in a bar to orchestrate a celestial dance. Making each one represent a different heavily body, he demonstrates that “even simple folk like us can understand immortality” by explaining the workings of the upcoming solar eclipse, as if to forestall the superstitious doom-mongering that might be smuggled in on the back of cosmic phenomena. His attempt to give these men a sense of their own significance in the cosmos can be seen to have failed later on when they are seen submitting themselves to outbursts of senseless violence, unable to defy the inexorable march of a primed, prompted mob. This is a beautiful opening, with a magnificent incongruence between the grubby, sozzled men and the solar system they obligingly mime. It’s darkly comic but utterly beguiling with its insistent, repetitive rhythms, plaintive score and those graceful camera movements that iron out the stumbling awkwardness of its participants and turn them into a poised summary of a harmonised universe. Then they all get turfed out onto the street at closing time. Everything after this point is a departure from that order, and János is never again shown to have such omniscience, insight or influence. But we’re ten minutes in, and we still don’t know what’s going on? Hurry things along please, Mr. Tarr…

Why do we need to see very long takes of a figure walking down a road into a vanishing point? Surely we just need a brief shot of them walking away from the camera and, because we’re clever people, we can just assume that they’ll continue heading in that direction? Why do we need to see the marching crowd marching for so long? We get the point that they’re heading somewhere, and that they mean business, after just a few moments? What’s the point of extruding the shot for what seems like an unnatural and unnecessary duration? These are all good questions, to which there is no simple answer, unless we just turn them around and ask why we insist that shots must serve only a narrative function? But I’d rather you try to engage with these shots and think about what we’re supposed to do with them. Where do you look, and what are you to understand from the shots that you couldn’t understand if they were much shorter?

To use the example of the marching mob, this is a shot whose extended duration could be understood in realist terms: we see them marching for as long as it takes for them to reach their destination, as if to reinforce the inevitability of their mission, the undeflected solidarity of their group. The continuous rhythm of their stomping feet becomes an empathetic noise, conveying the mindless hypnotic state that seems to have gripped them. The next shot is of the mob’s ransacking of a hospital, a sequence of wordless violence (and all the more unsettling for not being backed up with slogans, chants, shouts or screams) that culminates in a moment of devastating poignancy, an image of individual frailty amidst the bludgeoning force of the crowd that turns things around in an instant. We could see these two tracking shots as the build-up to this pay-off, and it seems all the more powerful for the way it overrules in a matter of seconds the march that has lasted for so long. I won’t give away what happens for those who haven’t seen it yet, but if you try to imagine this sequence cut down to a fraction of its length, you could get the same story information from it, but not without depleting its poetic power.

That’s an easy example. Why, though, do we need to see so much walking, so much food preparation, so much standing around in the fog? David Bordwell addresses the question of long takes in Tarr’s later films, such as Werckmeister Harmonies and his seven-hours-plus masterpiece Sátántangó, arguing that they “don’t present a beginning-middle-end structure”:

We simply follow a character walking toward or away from us, pushing into a stretch of time whose end isn’t signaled in any way. This becomes especially clear in those extended long shots in which a character walks away toward the horizon and the camera stays put. Traditionally, that signals an end to the scene, but Tarr holds the image, forcing us to watch the character shrink in the distance, until you think that you’ll be waiting forever. Likewise, the diabolical dance shots of Sátántangó, built on a wheezing accordion melody that seems to loop endlessly, are exhausting because no visual rhetoric, such as a track in or out, signals how and when they might conclude. Early and late, Tarr won’t hold out the promise of a visual climax to the shot, as Angelopoulos does; time need not have a stop. […] Like Tarkovsky, he shifts our attention from human action toward the touch and smells of the physical world … [He] employs “dead time” and landscapes to create a palpable sense of duration and distance.

Tarr was also asked about the long takes by Eric Schlosser, and gave the following reply:

You know I like the continuity, because you have a special tension. Everybody is much more concentrated than when you have these short takes. And I like very much to build things, to conceive the scenes, how we can turn around somebody, you know, all the movements implied in these shots. It’s like a play, and how we can tell something, tell something about life… Because it’s very important to make the film a real psychological process…

I said at the beginning that I didn’t want to stop you having your own personal responses to this film, but that shouldn’t really need saying. At the risk of sounding pretentious, it’s not a film from which you can just gather the plot details and leave it at that. In those long stretches where little seems to be happening, or the same thing just continues to happen in the same way, you have time to think and to feel, to marvel at the graphic beauty of a shot supremely achieved, or to immerse yourself in another time and place – by not haranguing you with the next piece of narrative information, Tarr pushes you into confronting the passage of time, to feel the weight of stasis as opposed to formulaic forward progression. Perhaps the question should not be “why is Werckmeister Harmonies so slow?” Rather we should ask ourselves some serious questions about our customary relationships with film, and why we expect it to move at a particular pace and provide packets of entertaining rewards at regular intervals: without ever resorting to cosmic or abstract imagery, Tarr has made a film about free will, evil, death, violence, and humanity’s place in a universe of imponderable patterns and structures (hence János’ urgent attempt to get his barfly planets to share, and thus master their trepidation about the scale of things around them, to see themselves as part of a a greater harmony). This may also give us a clue to the significance of György the musicologist’s musings about the musical/universal disjunctures caused by the work of Andreas Werckmeister, whose theories on counterpoint were connected to the arrangement of the planets in the Solar System (I’d appreciate any elaboration on this point from anyone who has the specialist knowledge to explain it to me…). Given all this, why on earth would you want it to hurry up? Did you have something more important to think about today?

http://drnorth.wordpress.com/2008/11/09/how-to-watch-werckmeister-harmonies/