A serious proposal to the ladies, for the … – Internet Archive

A serious proposal to the ladies, for the … – Internet Archive

Mary Astell : “Se tutti gli uomini sono nati liberi perché le donne sono nate schiave?”

Le donne “non hanno nulla da fare se non glorificare il Signore e chiacchierare con le vicine”.

“Ma come si può esser contente di star al mondo come tulipani in un giardino, per offrire un grazioso spettacolo e non servire a nient’altro?”

(Mary Astell, A Serious Proposal to Ladie)

La grande intuizione di Mary Astell è, appunto, che il comportamento femminile non è frutto della natura, ma del condizionamento sociale e che le donne hanno diritto a non sposarsi prima dei diciotto anni per sviluppare le loro potenzialità. Fu un’eccezione per i suoi tempi. Creò l’immagine della donna colta, che può scegliere di vivere da sola, preparando la strada alle tesi dell’ emancipazione femminile affermatesi nel XVIII secolo.

Infatti, pur nelle ristrettezze economiche della famiglia, ella si dedicò a studi filosofici e letterari, amando Milton, Spenser, Cowley, l’ “impareggiabile Orinda” (Katherine Philiphs). Abbandonata l’originaria Newcastle per Chelsea, perseguì, attraverso notevoli difficoltà, il disegno di fondare un monastery, una comunità femminile in cui le donne avrebbero potuto dedicarsi agli studi e alle devozioni, specie nel caso avessero rifiutato il matrimonio. Per difficoltà finanziarie l’esperimento fallì.

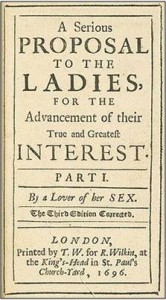

L’originalità del suo pensiero è espressa soprattutto nell’opera dal titolo “Una seria proposta alle donne“, dove, nella prima parte, Mary Astell sostiene la necessità di una maggiore istruzione femminile e, nella seconda, offre un piano di studi inteso a guidare le menti delle studentesse “prese sul serio” per la prima volta.

In “Riflessioni sul matrimonio“, invece, Mary Astell indica lo squilibrio tra i due poteri che caratterizzano il matrimonio e afferma: “L’uomo generalmente prende moglie perché ha bisogno di una che regga la famiglia, una serva di categoria superiore il cui interesse non sia in contrasto con il suo…una che egli possa governare da cima a fondo…che sia sua per tutta la vita e che non possa lasciare il suo servizio in qualunque modo egli la tratti“.

Nonostante questa fosca immagine coniugale, la Astell non auspica la ribellione domestica da parte delle donne, mette piuttosto in discussione l’autorità maritale ma solo ai fini del miglioramento della condizione femminile. Pur non riuscendo a realizzare il suo progetto del monastery, Mary Astell ebbe un forte seguito tra le donne colte dell’aristocrazia e riconoscimenti da tutta la società del suo tempo. Basti qui ricordare l’editore Rich Wilkin, che nel 1694 pubblicò il suo primo libro e così farà per tutte le sue opere – sia quelle rivolte alle donne che quelle di carattere politico e religioso – nei trentasei anni successivi.

Ella ancora oggi viene citata come donna colta, filosofa, poeta, letterata dallo stile molto arguto e piacevolmente ironico.

(Carla Cecchini Rocchi)

http://www.antrodellasibilla.it/ritr_euocc1.htm

Mary Astell (1666 – 1731)

Mary Astell is often called the first English feminist, but her views on women would dismay any modern liberal. She was an unshakeable Tory Anglican who dared to cross swords with the great liberal thinker John Locke. For many admirers it’s not her womanhood at all which requires to be admired: it’s her sheer intellect – she was a brilliant philosopher with a very, very sharp pen.

One of two great women writers of her generation to emerge from the obscurity of Newcastle (the other was the first scholar to produce an English- Anglo-Saxon dictionary, Elizabeth Elstob), she lived her adult life in London among a glittering array of thinkers, many of them formidable women who pass muster as an early Enlightenment all of their own. The short-reigning Queen Anne was an inspirational patroness. The religious/political fervour of the period between two civil wars and the Jacobite uprising, during which the British monarchy was in almost permanent crisis, provides a vivid backdrop.

Mary Astell never married. Indeed, she was uninterested in love; logic and rationality were her passions, above all in the fields of religion, constitutional reform and the social contract on which she held startling, penetrating views. She would have got on famously with Christine de Pizan; perhaps also with Celia Fiennes, whom she may have met. She had many male admirers and quite a number of enemies; few of the latter could hold their own against her.

Some of her views may now seem rather retrograde; others are expressed with the sort of rhetorical power that cannot be refuted. But as a shining light in London’s early 18th century intelligentsia she deserves a much more prominent place than she has yet been allowed in the line of great British thinkers (and writers about thinking) which runs from Hobbes and Locke through to David Hume, Adam Smith and JS Mill.

If all men are born free, how is it that all women are born slaves?

Some Reflections upon Marriage 1700.

Hitherto I have courted Truth with a kind of Romantick Passion, in spite of all Difficulties and Discouragements: for knowledge is thought so unnecessary an Accomplishment for a Woman, that few will give themselves the Trouble to assist us in the Attainment of it.

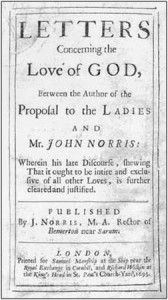

Letters Concerning the Love of God. Letter V.

Seeing it is ignorance, either habitual or actual, which is the cause of all Sin, how are they like to escape this, who are bred up in that? That therefore women are unprofitable to most, and a plague and dishonour to some Men is not much to be regretted on account of the Men, because ’tis the product of their own folly, in denying them the benefits of an ingenuous and liberal Education.

A Serious Proposal to the Ladies, Part I 1694

To be yok’d for Life to a disagreeable Person and Temper; to have Folly and Ignorance tyrannize over Wit and Sense; to be contradicted in every thing one does or says, and bore down not by Reason but Authority; to be denied one’s most innocent desires, for no other cause but the Will and Pleasure of an absolute Lord and Master, whose Follies a Woman with all her Prudence cannot hide, and whose Commands she cannot but despise at the same time she obeys them; is a misery none can have a just Idea of, but those who have felt it.

Some Reflections upon Marriage

If none were to Marry, but Men of strict Vertue and Honour, I doubt the World would be but thinly peopled.

Some Reflections upon Marriage

If a Woman can neither Love nor Honour, she does ill in promising to Obey.

Some Reflections upon Marriage

The short is; The true and the principal Cause of that Great Rebellion, and that Horrid fact which compleated it, and which we can never enough deplore, was this: Some Cunning and Self-ended Men, whose Wickedness was equal to their Craft, and their Craft sufficient to carry them thro’ their Wickedness; these had Thoughts and Meanings to destroy the Government in Church and State, and to set up a Model of their own Invention, agreeable to their own private Interests and Designs, under the specious Pretences of the Peoples Rights and Liberties. They did not indeed speak out, and declare this at first, for that wou’d have spoil’d the Intrigue, every body wou’d have abhorr’d them; but a little Discernment might have found what they drove at. For to lessen and incroach upon the Royal Authority, is the only way to null it by degrees, as an ingenious Person observes upon this Occasion.

An Impartial Enquiry … 1704

Mary Astell timeline

1666 Born Newcastle, daughter of coal trader and Hostman who dies 1678

1684 Mother dies

1685 Accession of James II

1686 Mary Astell moves to London, takes up residence in Chelsea

1688 Glorious Revolution: William III and Mary II replace deposed James II

1689 Bill of Rights; Toleration Act gives freedom to Protestant dissenters

Astell: A collection of poems to Archbishop Sancroft;

John Locke: Two Treatises of Government

1690 John Locke: An Essay concerning Human Understanding

1693 Astell begins correspondence with John Norris

1694 Queen Mary dies childless; Astell: A Serious Proposal to the Ladies

1700 Astell: Some Reflections on Marriage.

1701 Act of Settlement establishes Hanoverian claim on throne

1702 William III dies; Anne, daughter of James II, succeeds

1704 Astell: A Fair Way with the Dissenters; An impartial inquiry into the causes

of Rebellion and Civil War in this Kingdom; John Locke dies

1714 Queen Anne dies childless; George I succeeds

1715 The ‘Fifteen’ northern Jacobite uprising;

Elizabeth Elstob: Rudiments of Grammar for the English-Saxon tongue

1716 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu leaves for Istanbul as Ambassador’s wife

1726 Dean Swift: Gulliver’s Travels

1727 George I dies; succeeded by George II

1731 Mary Astell dies

http://www.theambulist.co.uk/words-and-musings/heroines-seven-women/mary-astell