Paradox at the heart of mathematics makes physics problem unanswerable

Gödel’s incompleteness theorems are connected to unsolvable calculations in quantum physics.

A logical paradox at the heart of mathematics and computer science turns out to have implications for the real world, making a basic question about matter fundamentally unanswerable.

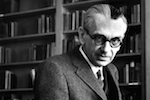

In 1931, Austrian-born mathematician Kurt Gödel shook the academic world when he announced that some statements are ‘undecidable’, meaning that it is impossible to prove them either true or false. Three researchers have now found that the same principle makes it impossible to calculate an important property of a material — the gaps between the lowest energy levels of its electrons — from an idealized model of its atoms.

The result also raises the possibility that a related problem in particle physics — which has a US$1-million prize attached to it — could be similarly unsolvable, says Toby Cubitt, a quantum-information theorist at University College London and one of the authors of the study.

The finding, published on 9 December in Nature1, and in a longer, 140-page version on the arXiv preprint server2, is “genuinely shocking, and probably a big surprise for almost everybody working on condensed-matter theory”, says Christian Gogolin, a quantum information theorist at the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Barcelona, Spain.

From logic to physics

Gödel’s finding was first connected to the physical world in 1936, by British mathematician Alan Turing. “Turing thought more clearly about the relationship between physics and logic than Gödel did,” says Rebecca Goldstein, a US author who has written a biography of Gödel3.

Turing reformulated Gödel’s result in terms of algorithms executed by an idealized computer that can read or write one bit at a time. He showed that there are some algorithms that are undecidable by such a ‘Turing machine’: that is, it’s impossible to tell whether the machine could complete the calculations in a finite amount of time. And there is no general test to see whether any particular algorithm is undecidable. The same restrictions apply to real computers, since any such devices are mathematically equivalent to a Turing machine.

Since the 1990s4, theoretical physicists have tried to embody Turing’s work in idealized models of physical phenomena. But “the undecidable questions that they spawned did not directly correspond to concrete problems that physicists are interested in”, says Markus Müller, a theoretical physicist at Western University in London, Canada, who published one such model with Gogolin and another collaborator in 20125.

“I think it’s fair to say that ours is the first undecidability result for a major physics problem that people would really try to solve,” says Cubitt.

Spectral gap

Cubitt and his collaborators focused on calculating the ‘spectral gap’: the gap between the lowest energy level that electrons can occupy in a material, and the next one up. This determines some of a material’s basic properties. In some materials, for example, lowering the temperature causes the gap to close, which leads the material to become a superconductor.

The team started with a theoretical model of a material: an infinite 2D crystal lattice of atoms. The quantum states of the atoms in the lattice embody a Turing machine, containing the information for each step of a computation to find the material’s spectral gap.

Cubitt and his colleagues showed that for an infinite lattice, it is impossible to know whether the computation ends, so that the question of whether the gap exists remains undecidable.

For a finite chunk of 2D lattice, however, the computation always ends in a finite time, leading to a definite answer. At first sight, therefore, the result would seem to have little relation to the real world. Real materials are always finite, and their properties can be measured experimentally or simulated by computer.

But the undecidability ‘at infinity’ means that even if the spectral gap is known for a certain finite-size lattice, it could change abruptly — from gapless to gapped or vice versa — when the size increases, even by just a single extra atom. And because it is “provably impossible” to predict when — or if — it will do so, Cubitt says, it will be difficult to draw general conclusions from experiments or simulations.

Million-dollar question

Cubitt says that the team ultimately wants to study a related problem in particle physics called the Yang–Mills mass-gap problem, which the Clay Mathematics Institute in Peterborough, New Hampshire, has named one of its Millennium Prize Problems. The institute is offering $1 million to anyone who is able to solve it.

The mass-gap problem relates to the observation that the particles that carry the weak and strong nuclear force have mass. This is also why the weak and strong nuclear forces have limited range, unlike gravity and electromagnetism, and why quarks are only found as part of composite particles such as protons or neutrons, never in isolation. The problem is that there is no rigorous mathematical theory which explains why the force-carriers have mass, when photons, the carriers of the electromagnetic force, are massless.

Cubitt hopes that eventually, his team’s methods and ideas will show that the Yang–Mills mass-gap problem is undecidable. But at the moment it doesn’t seem obvious how to do it, he says. “We’re a long way from winning the $1 million.”

- Nature

- doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18983

Se il problema quantistico è irrisolvibile

Primo problema matematico non risolvibile per una delle questioni fondamentali della fisica particellare e quantistica, quello dello “spectral gap”. Anche una descrizione perfetta e completa delle proprietà microscopiche di un materiale potrebbe essere insufficiente a determinare semiconduttori e superconduttori

Provata irrisolvibilità del problema. È questo il responso dei ricercatori dello University College di Londra, della Universidad Complutense di Madrid e dello ICMAT di Monaco. Il loro studio, appena pubblicato su Nature, parla chiaro: abbiamo il primo problema matematico non risolvibile per una delle questioni fondamentali della fisica particellare e quantistica.

Anche una descrizione perfetta e completa delle proprietà microscopiche di un materiale potrebbe non essere sufficiente a prevedere il suo comportamento macroscopico. Quello che tecnicamente viene chiamato “spectral gap”, ovvero l’energia necessaria a eccitare un elettrone (tanto importante nei semiconduttori e che gioca un ruolo importante anche in molti altri materiali) potrebbe risultare qualcosa che è impossibile determinare. Non decidibile, in lingua matematica.

E pensare che fino a ieri il calcolo matematico della struttura microscopica dei materiali è stata ritenuta fondamentale per determinare cosa possa rivelarsi un ottimo superconduttore a temperatura ambiente, tanto per fare un esempio. Se il risultato dei calcoli riportati su Nature è attendibile, c’è da ripensare completamente l’approccio alla ricerca di nuovi semiconduttori e superconduttori.

«Alan Turing è famoso in tutto il mondo per aver violato il codice cifrato dei nazisti: Enigma. Tra matematici e informatici è anche più famoso per aver dimostrato come alcuni problemi matematici siano irrisolvibili. Lo spectral gap sembra essere uno di questi problemi», spiega Toby Cubitt dello University College di Londra. «Un fatto che mina alla base la nostra capacità di prevedere il comportamento di alcuni materiali quantici e, potenzialmente, anche di alcune particelle fondamentali della fisica».

Ora: il modello standard della fisica particellare ha o non ha uno spectral gap? Gli esperimenti di fisica particellare condotti dal CERN di Ginevra sembrerebbero suggerire di sì. E c’è anche un premio da un milione di dollari del Clay Mathematics Institute per chi riesca a dimostrare matematicamente la pletora di equazioni che sottendono al modello standard. «Può anche darsi che per alcuni casi particolari il problema preveda una soluzione anche se in generale è irrisolvibile. Certo è che con il nostro studio aumentano le probabilità che alcuni grandi problemi della fisica possano dimostrarsi ed essere dimostrati come irrisolvibili», ha precisato Cubitt.

«Sapevamo della possibilità che alcuni problemi matematici possano restare “non decidibili”. Ma abbiamo sempre pensato fosse un tema che riguardava esclusivamente la logica matematica e l’informatica teorica. Nessuno ha mai pensato che questo genere di astrazioni potesse riguardare la fisica particellare e quantistica. Ora tutto cambia», spiega Michael Wolf dello ICMAT di Monaco. «Non tutto il male viene per nuocere», ricorda però David Pérez-García dalla Universidad Complutense di Madrid. «Questa anomalia, se così possiamo chiamarla, nel modello standard apre le porte a nuove e interessanti ipotesi. I nostri risultati dimostrano, per esempio, che l’aggiunta di anche una sola particella a un grumo di materia, per quanto grande possa essere, può teoricamente trasformare anche in modo radicale le sue proprietà. Una scoperta che potrebbe avere, come è già successo in passato, importanti ricadute dal punto di vista tecnologico».

http://www.media.inaf.it/2015/12/09/se-il-problema-quantistico-e-irrisolvibile/