Weaponizing Anthropology: An Overview

Posted on August 19, 2014 by Maximilian Forte

By David H. Price. Published by CounterPunch and AK Press, Petrolia and Oakland, CA, 2011. ISBN-13: 9781849350631. 219 pages.

For students already in anthropology and those interested in perhaps becoming anthropology students, for those researching the history and political economy of the social sciences, and for members of the wider public who want to understand the deep and broad transformations wrought by the latest round of US imperial expansion since 2001, David H. Price’s Weaponizing Anthropology is indispensable reading. That statement is not just gratuitous praise: I in fact assigned the text as required reading in my 2014 graduate seminar, New Directions in Anthropological Research, in which students were required to post review essays of every book covered in the course, including this one (elsewhere, one can also read strong reviews by Jeremy F. Walton, Eliza Jane Darling, and Robert Lawless). Of the books covered in that semester, Price’s probably was the most compelling for students. The book, mostly based on edited, expanded and updated versions of previously published essays, is a succinct yet dense description and analysis of the militarization and securitization of American anthropology following the US’ launch of its “war on terror” since 2001, and the US invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq. For over two decades Price has been “studying up” the US national security state, through interviews, analysis of leaked documents, and research using state and university records and records gained under freedom of information access laws, and this book adds to the two he has already published on these topics, while giving us a little preview of his upcoming volume on the CIA’s relationships with American anthropology. In this volume, Price offers a critical overview of the ethical stakes and political consequences of the renewed incursion of the CIA onto US university campuses, the appropriations of anthropology for the purposes of counterinsurgency in Afghanistan and Iraq, and in general the uses by military and security apparatuses of “cultural knowledge” as a strategic tool for the purpose of conquest and control. Price takes us through various intelligence programs that enlist academics, such as the Pat Roberts Intelligence Scholars Program and the CIA’s Intelligence Community Centers of Academic Excellence (ICCAE), and the military programs that recruit social scientists, such as the Human Terrain System (HTS) and the Minerva Research Initiative, both run by the Pentagon.

Weaponizing Anthropology points to ways that militarization and securitization—the ideologies and processes of national security—are tied to imperialism and the political economy of academia in the US. As Price explains, “the political economy of American academia needs to be critically examined as linked to the dominant militarized economy that supports American society” (p. 5). The book is divided into three parts, the first dealing with intelligence agencies on US campuses, the second focusing on a critical analysis of key manuals produced by the US military, and the third part examines counterinsurgency. What I want to do here is not so much “review” the book, as others have already done very well, but to provide a detailed overview, with some discussion, that largely follows the same order of parts and chapters presented in the book. First, however, I will present Price’s contributions to the discussion of imperialism and anthropology, and then the militarization of anthropology.

Imperialism and Anthropology

As Price explains in his introduction, “Anthropology’s Military Shadow,” George W. Bush’s “war on terror” involved rediscovering “old militarized uses for culture” and it “invigorated new modernist dreams of harnessing anthropology and culture for the domination of others” (p. 1). Anthropology, for its part, “has always fed between the lines of war. Whether these wars rage hot in the immediate foreground of fieldwork settings or influence the background of funding opportunities, wars and the political concerns of ‘National Security’ have long influenced the development of anthropological theory and practice” (p. 11). This comes to the fore in the case of applied or “development anthropologists” who have long been engaged in “selling the promises of modernization to those who would be displaced and damaged by the ‘progress’ to come” (p. 14). Early anthropologists, Price observes, “filled that complex hole of empire’s knowledge base with a useful understanding of culture that was both enlightened and mercenary” (p. 14). Imperialism and anthropology were intertwined from the outset:

“Anthropology’s roots grew in the soils of established military might in lands conquered by European powers, often some years after military forces laid conquest. The arrival of anthropologists often followed a progression of arrivals that flowed from infantries, to plantation or mining engineers, missionaries, then finally: anthropologists”. (p. 14)

National traditions of ethnology and anthropology emerged once the British, Dutch, French, German, and American empires spread around the globe (p. 14). “The needs of colonialism,” as Price points out, “often required some knowledge of the occupied populations they sought to manage, and anthropology was born” (p. 14). Anthropology contributed towards “maintaining the structure of power represented by the colonial system” (p. 15). In the US, early anthropologists working in the Bureau of American Ethnology and federal agencies organized under the Department of the Interior, sometimes had direct commerce with the US Army, that is, with “agencies relocating, undermining and controlling Indian populations” (p. 15). In passing Prices notes that Franz Boas also had “serious ethical shortcomings,” as shown in his “scandalous involvement in grave robbing” (p. 17). In a very basic sense, whether conscious and critical or not, anthropologists have long known about “counterinsurgency” before it acquired its recent mystique and cult-like following among US militarists.

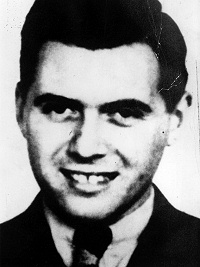

Paging Dr. Mengele

In “War is a Force that Gives Anthropology Ethics,” which I would argue is one of the most important chapters written in American anthropology in the last 20 years, Price continues to outline the ways that anthropology has historically been implicated with power. By way of the research of Gretchen Schafft (who also reviewed this book in the American Anthropologist, 2012, Vol. 114, No. 4, pp. 708-709), who looked into Joseph Mengele’s formal anthropological training, what is revealed is that “the anthropologist with the highest name recognition in all of history was not Margaret Mead, but was instead Joseph Mengele” (p. 20, emphasis added). As Price adds, “that most anthropologists have no idea that Mengele was formally trained in anthropology is a small but significant monument to the ways that the discipline has divorced itself from its historical interactions with power” (p. 20).

I would argue that Price is necessarily commenting on American anthropology and its selective memory and partial acts of recognition, and it would have been better to emphasize that what Price is talking about throughout his book is not all anthropology as such, but American anthropology in particular.

Booting Margaret Mead

Continuing from his voluminous research into US anthropology in the Cold War years, Price reminds us that the “Cold War’s showers of previously unimaginable public and private funds for anthropological research shifted anthropological imaginations in ways aligned with geopolitics” (p. 22). There are far too numerous cases to adequately summarize, but Price notes some of the key ones, such as anthropologists employed by the CIA and its precursor, the OSS, as well as anthropologists involved in the internment of Japanese Americans, in Project Camelot, in the Human Ecology Fund, in the RAND Corporation and in USAID. Here Price brings us back to Margaret Mead and her disgraceful 1971 “report” for the American Anthropological Association, and her shameful attacks against Eric Wolf and others for their publicizing the identities of anthropologists working in counterinsurgency programs in Thailand, for example.

Militarizing Anthropology

Much of the militarization that has taken place, post-9/11, Price argues is the result of a “perfect storm” that combines new fear and new sources of funding, in a context of stagnant or reduced funding for academia from non-military sources (p. 1). In turning to anthropology, one of Price’s core arguments in the book is that “the American military clearly misunderstands just how much difference cultural competence could make in hiding the nakedness of American mercenary ventures” (p. 3). The second error is to be found in the modernist mystique built around the “new” (and once again quite discredited) counterinsurgency doctrine spearheaded by disgraced Gen. David Petraeus. As Price reminds those who need reminding, “there is nothing modern in recognizing that if one can get enemy populations to give up their traditional means of economic independence and make them dependent upon occupiers for health or economic well-being, one can undermine traditional systems of governance and dominate these populations” (p. 12). Indeed, Price goes back to 1803 (he could also have gone back to 1492), and to Thomas Jefferson, and the wars against Indians to take their lands, displace them, erode their cultures, and turn them into dependents (p. 14).

Much of the apparent confusion in the military about what it can and should not use in anthropology, “is exacerbated by the anthropologists who often misrepresent the discipline and its skill sets as they sell their wares to an eager military hungry for answers” (p. 3). The confusion also stems from anthropology itself and how it has been shaped in an imperial context, as Price also notes that, “anthropology has always been funded to ask certain types of questions, or to know certain types of things: sometimes this has meant that there were more funds available to study the languages and cultures of specific geographic regions, in other times this meant entire theoretical approaches were fundable (like the simplistic culture and personality studies of the post war period, used to study our enemies at a distance), while others (critical Marxism, ca. 1952), were not” (p. 2).

The Politics of Anthropology (and Memory)

David Price is quite sensible in coming to an estimation of what he is up against, not just in terms of forces external to academia, but also those that lie within. “Somewhere between 1971 and today,” Price remarks, “American anthropologists lost their collective sense of outrage over the discipline being so nakedly used for counterinsurgency,” and one reason for that is the “degeneration of historical memory,” he argues (p. 28). Price adds that “fewer Americans know the history of the CIA’s legacy of assassinations, coups and death squads and a history of undermining democratic movements” (p. 28). Add to this the increased corporatization of the university, the fear around the loss of funding, progressively diminished academic independence, self-censorship, and the jingoism of a “fervently militarized” post-9/11 US, Price notes. As one result, we have a case where “the discipline as a whole refrains from stating outright opposition to anthropologically informed counterinsurgency” (p. 28). Even now there is still a bias against “political” critiques: “there remains a great resistance to confronting the ways that disciplinary ethics are linked to the political context in which anthropology is practiced” (p. 30).

Instead, what we get are “critiques of manners and techniques” (p. 31). Professional concerns with the ethics of research and following “best practices,” betray a certain shallowness—Price argues we need to understand “just how problematic notions of ‘best practices’ are if they don’t include basic political stances like opposing imperialism, neocolonialism, and supporting the rights of nations to self-determination” (p. 30). Price takes aim at professional associations, such as the AAA, and this would be based on first-hand experience as a member of two AAA commissions dealing with anthropology, the military, intelligence agencies, and the Human Terrain System. He writes that professional associations focused on ethics, while sidestepping politics, “ignore the larger political issues of how anthropological engagements with military, intelligence, national security sectors relate to US foreign policy” (p. 31). Instead, he says, associations like the AAA try to position themselves as neutral, when instead what they are doing is acquiescing through silence (p. 31).

Many of the issues and questions raised in this book have been thrashed in the pages of ZA for several years now, so I will keep my comments brief. Much of what anthropologists and other disciplinary associations treat as “ethics” is instead just a partial slice, a particular rendition of what they are willing to consider as ethics. Usually, the philosophy behind what they chose to encompass as ethics, comes from deontological approaches. Price is more of a consequentialist, an approach that would not artificially divorce the ethical from the political. I think his approach is superior: what makes something ethical, and what makes the ethical necessary, is ultimately rooted in some conflict over differences of power. Secondly, Price may be in a bigger uphill battle than some would recognize when it comes to questioning and challenging anthropological complicities. He defines his subject somewhat narrowly and in parts; we thus see a proliferation of terms such as militarization, intelligence, the national security state, etc. But, since these are not disparate and unrelated components, what are all of these combined, of what whole are they components? Price is onto an answer when he mentions imperialism. Imperialism, however, is much broader than militarization. Questioning and challenging US anthropologists who work as the eyes and ears for US foreign policy means more than just tackling the presence of the Pentagon and CIA; it requires that one also tackle the State Department, USAID, the Peace Corps, the mainstream media, banks, etc. With a broader purview, Price would encounter very many US anthropologists who are complicit with power, some of whom may have also publicly denounced the Human Terrain System and distanced themselves from militarization. Some, like those I have tracked, wrote skewed articles that effectively glamorized anti-government protesters in Ukraine before the coup, while tilting with jingoistic gusto against “Putin” and “pro-Russia” protesters; others openly sell their consulting services to the US State Department, to inform US policy of “key players” in the conflict in the Central African Republic; while many more engage themselves with aiding “humanitarian” interventions. The third point is one for the rest of us, non-Americans: how do we engage with American anthropologists knowing how so many of them collaborate, to different degrees, with reinforcing and sustaining US power?

The CIA on Campus, Again

Part 1, which occupies nearly half of the total number of pages in the book, focuses on the CIA’s efforts to reinsert itself in US campuses, with considerable success. In particular, the Intelligence Community Centers of Academic Excellence (ICCAE) link campuses to the CIA in some new ways, such as by actively recruiting women and minority students via events such as “CIA Day” at Trinity Washington University. Price explains that university classrooms are being transformed into “covert training grounds for the CIA” and other intelligence agencies, “in ways that increasingly threaten fundamental principles of academic openness as well as the integrity of a wide array of academic disciplines” (p. 33). The credibility of American academics could be seriously damaged as a result of whole spate of intelligence links to US universities, something apparently not at the forefront of the minds of academics who act as “compliant appendages of the state” (p. 53). Today, US academia “is increasingly tethered to hidden patrons and clients,” while “the number of dissident scholars is easily exaggerated” (pp. 53, 55).

Intelligence “community”? One cannot expect to use a term like “community” and to get away with it when a critical anthropologist is present. Price speaks of “the CIA’s colonization of America’s consciousness” (p. 72), adding to Catherine Lutz’s conceptualization of “the military normal,” which she explained as the case where “core militarism reaches into all elements of cultural life until its presence is seen as proper, normal and good” (p. 71). Focusing on “community,” as in “the intelligence community,” Price takes note of “the self-christened innocuous phrase of desensitized preference,” and the function of the “soft inviting glow of using ‘community’ to refer to spy agencies devoted to anti-democratic means, imperialism, torture” (p. 72). Buying into the “normal, soft and natural feel” of the CIA and similar apparatuses as a “community,” is just “one small example of how we are all being socialized to accept intelligence agencies as part of the normal fabric of American life” (p. 72).

Speaking of the post-9/11 “pall of orthodoxy” that has swamped critical discussions of militarization and national security (p. 77)—just as we read thousands of comments from neo-fascist military fundamentalists right here in ZA—Price calls on academics, especially tenured ones, to speak out and to put their tenure to its intended uses (p. 90). Against an agency that places such high priority on secrecy as the CIA does, “breaking the silence” becomes an effective resistance tactic (p. 89).

The reasons for removing the CIA from US campuses are many. Among those which Price emphasizes are: a) the “reprehensible deeds of the agency’s past” (although here he needed a word like “record” rather than “past,” since its reprehensible deeds more than just continue into the present and near future); b) the fact that the CIA on campus “further diminishes America’s intelligence capacity while damaging academia,” by narrowing the terms of discussion and essentially creating university echo chambers; and, c) because “the primary impact will be to transform segments of universities so that they learn to limit themselves and to adapt to the cultures of the intelligence agencies” (p. 87).

Deconstructing the Manuals of Cultural Warfare

Part 2 of the book provides many illuminating anthropological insights into four separate documents produced by the US military (in some cases with the help of military-employed social scientists), these being the Human Terrain Team Handbook, the Counterinsurgency Field Manual, the Stryker Brigade Report, and the Special Forces Advisor Guide (which are not analyzed in the chronological order of their publication).

As one of the leading critics of the US Army’s Human Terrain System (HTS), and thanks to a series of leaked documents published by WikiLeaks and sent on to David Price for review and commentary, Price begins with the Human Terrain Team Handbook. Overall, he finds that the Handbook contains an “underlying logic that anthropologically based non-lethal subjugation is good” (p. 102). The aim, as revealed by the Handbook, is “to make populations…‘legible’ and thus controllable” by “engineering the ‘trust of the indigenous population’” (p. 103). The problem is that HTS “compartmentalizes the project as something separate from neo-imperial missions of invasion and occupation” (p. 103). HTS supporters thus “insist they operate outside of any form of structural or historical forces” that link them to conquest (p. 103). Instead, HTS defenders seem to think that “declared good intentions and visions of reduced harm” are significant enough by themselves, and that their employees are somehow capable of transforming large bureaucracies, not just from within, but from the bottom up (p. 105).

Written at a level of “high school or middle school…sophistication,” the Handbook outlines simplistic methods to catalogue members of occupied populations for entry into remote databases, with an especial preference for network analysis and geospatial intelligence (p. 105). Guiding such methods are “neo-positivist notions that social control…can be achieved by the recording of, and then manipulation of key variables” (p. 106). HTS’ project of “social engineering” will supposedly be achieved by “simplistic, atheoretical notions of culture,” mixed in with some “marketing research techniques” (p. 106). Price concludes that the Human Terrain Team Handbook reflects “a broken high tech version of colonial projects that many anthropologists hoped had become part of a shameful disciplinary past” (p. 107). With the now glaringly obvious failures of counterinsurgency in Afghanistan and Iraq—failures predicted by critics like Price—it would be interesting to see HTS defenders, if any are left, try to argue against reality yet again. Maybe instead of serving as compliant boosters and cheerleaders, the mainstream media would be wise to give critics more space, and not cast them as caricatured outsiders.

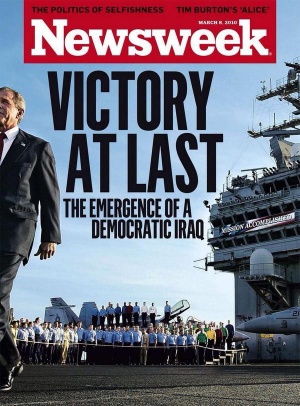

Price’s critique of the fake scholarship of the much touted Counterinsurgency Field Manual (FM 3-24) seems to be even sharper, better elaborated and reasoned in this rendition. I had made light of the documented plagiarism in the Manual (not expecting fine scholarship from the Pentagon), but Price explains why not taking that seriously is a big mistake. First, Price begins by noting how the new Field Manual was widely touted in the media as a “smart new plan,” with plenty of praise for its scholarship and open peer review process (p. 114). This was to be “a new intellectually fueled ‘smart bomb’” with a “brilliant new breed of scholars who could build culture traps for foreign foes and capture the hearts and minds of those we’d occupy” (p. 115). (Never mind their obvious inability to win over critics at home, with whom they shared language, culture, common forms of socialization and enculturation, etc.; somehow they would turn the Taliban against themselves.) Media propagandists were also furnished by the US Army itself, such as Robert Bateman (notorious for his many jejune comments and threats on this very site) who was the author of one such piece that is quoted by Price, and is now available only here.

Turning to the issue of plagiarism, in the Field Manual’s chapter 3 alone Price found 20 passages of direct use of others’ writing, without quotes, or heavy reliance on unacknowledged source materials (p. 116). Is it because the Field Manual cites none of its sources? No. The Field Manual does have a bibliography, references, and footnotes—but none of the anthropology and sociology sources that were used appear in any of those (p. 117). Why does that matter? Apart from being endorsed by a major university press (the University of Chicago Press), “the cumulative effect of such non-attributions is devastating to the Manual’s academic integrity, and claims of such integrity are the heart and soul of the Pentagon’s claims for the Manual” (p. 116).

Plagiarism matters, not because it is some sort of dispensable, superficial academic formality concocted by fastidious and pompous desk-warts, but for what it symbolizes. On one side, plagiarism in the Manual reflects a lack of original formulation and is “a useful measure of the Manual and its authors’ weak intellectual foundation” (p. 122). However, as Price adds, “the ways that the processes producing the Manual so easily abused the work of others inform us of larger dynamics in play, when scholars and academic presses lend their reputations, and surrender control, to projects mixing academic with military goals,” such as HTS (p. 124). As mentioned above, the Manual does indeed have footnotes and references—and these are used selectively. Price scrutinized this selectivity and found an interesting pattern:

“The instances in which the Manual does use quotes and attributions provides one measure of its status as an extrusion of political ideology rather than scholarly labor, as these instances most frequently occur in the context of quoting the apparently sacred words of generals and other military figures—thereby denoting not only differential levels of respect but different treatment of who may and may not be quoted without attribution”. (p. 125, emphases added)

It was this “fake scholarship” which was used as “a critical element of the Manual’s domestic propaganda function” (p. 126). Finally, what Price also highlights is what the Manual sets out as the role of anthropologists: “what the military wants from anthropology is to offer courses in local manners so they can get on with the job of conquest” (p. 130).

David Price then turns his attention to the third document, also published by WikiLeaks, the December 2004 “Army Stryker Brigade Initial Impressions Report on Operations in Mosul, Iraq”. The comments are not organized around any one theme, ranging from the Report’s praise for the willing complicity of embedded reporters in not reporting anything that might even slightly embarrass the military, to the authors’ frank acknowledgments of the difficulties they were facing in a complex environment that did not consist of people cheering US forces with offers of flowers and candy. The main point made by Price in this section has to do with how, from early on (just a year after the invasion of Iraq), the US military began to highlight the need for cultural knowledge, and how it envisioned the function of anthropologists: as pry-bars (p. 136).

In the final document analyzed, published by WikiLeaks in 2008, Price examines the Special Forces Advisor Guide (TC 31-73). The Guide, Price maintains, provides a significant opportunity for anthropologists “to critically consider not only the ends to which this desired anthropology will be put, but also the types of anthropology that the military seeks” (p. 140). For example, when it comes to “culture,” the Guide conceptualizes it as “nothing more than a measurable set of values that can be understood, compensated for, and therefore not only navigated but engineered to one’s advantage” (p. 141). The Guide holds firm to antiquated views of cultural “traits,” which are then linked to simplistic analyses of “personality,” based on ethnocentric assumptions. The Guide thus offers “crude culture characterizations” and “cartoonish representations of regional cultural stereotypes” (p. 142)—for a scathing reaction to these, see Lawless’ review of the book, which focuses on this document. The military, as Price observes, is “drawn to fantasies of hard science,” which has it endorsing such things as Kluckhohn and Strodtbeck’s “Values Orientation Model” (pp. 142, 145). The military wants identifiable elements that can be measured, because it is attractive to a military bureaucracy “so imbued with engineering” (p. 144). To speak of military anthropology then is to speak of the poverty of military anthropology.

Farewell to Counterinsurgency Fantasies

he final part of the book is a mixed collection of essays dealing with the present and future of counterinsurgency and drone warfare. What attracted me the most in this part of the book is that which will occupy this concluding section: counterinsurgency as fantasy.

While the Counterinsurgency Field Manual discussed above deploys the words of Max Weber, as a gloss of authority and respectability, it fails to examine “how historically difficult it is for external occupiers to acquire the forms of legitimacy that Weber recognized” (p. 187). Price quotes from William Polk’s 2007 book, Violent Politics, on this point: “the single absolutely necessary ingredient in counterinsurgency is unlikely ever to be available to foreigners,” and that ingredient is legitimacy (p. 187). The counterinsurgency theorists of today fancy themselves as being able to get the occupied to “internalize their own captivity as ‘freedom’” (p. 188). This reflects a delusional quality on the part of the COIN gurus.

For me, one of the most poignant comments comes towards the end of the book: “once a nation finds itself relying on counterinsurgency for military success in a foreign setting, it has already lost” (p. 190). A senior French commander speaking to a journalist is quoted as explaining, “we do not believe in counterinsurgency,” because “if you find yourself needing to use counterinsurgency it means the entire population has become the subject of your war, and you either will have to stay there forever or you have lost” (p. 191). As I write, the US has returned to war in Iraq, while in Afghanistan it seeks to force acceptance of a residual number of thousands of US troops to remain in the country for many years to come.

http://zeroanthropology.net/2014/08/19/weaponizing-anthropology-an-overview/