SCREEN: AGNES VARDA’S ‘VAGABOND’

SCREEN: AGNES VARDA’S ‘VAGABOND’

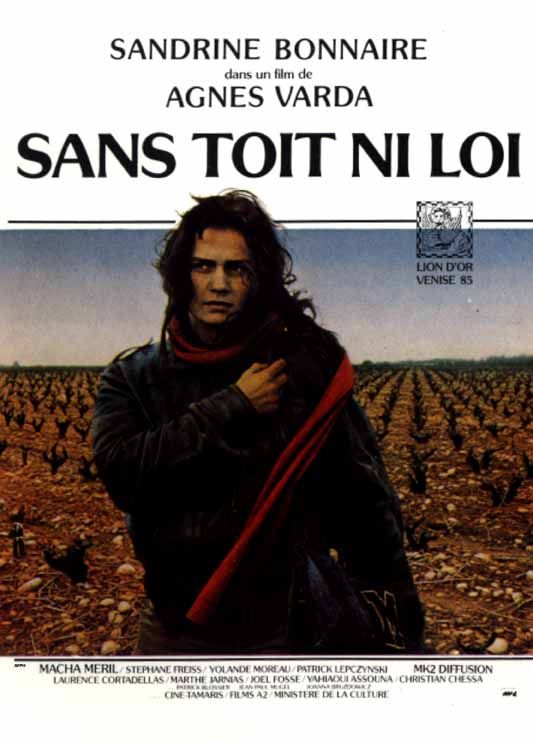

FROM the start of Agnes Varda’s ”Vagabond” – when her painterly director’s eye moves slowly through frozen vineyards to discover the body of a young woman – to the end, when she has circled back over the final weeks in this teen-age drifter’s life, her camera comes to rest again and again on the heroine’s extraordinary, mysterious face. It is a broad-featured, clear-eyed face that needs to be scrubbed clean, belonging to a woman who seems both scowling and innocent, whose sultriness owes something to the dark circles under her eyes.

We know little about Mona (Sandrine Bonnaire), only that she was a secretary who hated bosses, and is now a vagabond wandering through southern France in winter. So Miss Varda forces us to respond to externals, and turns a great risk into a triumph by making Mona difficult to like or understand. Tough and belligerent, with stringy hair and dirty fingernails, she is, as the French title reveals, ”Sans Toit ni Loi,” without roof or law. As we meet the people she last encountered – a leftover hippie who raises goats, a maid who lets her squat in an unused house, a well-dressed woman who picks her up hitchhiking – the film’s structure reflects Mona’s unanchored life. The narrative loops back and forth among the characters, all the while pulling us toward her death.

Miss Varda’s experience as a documentary film maker frames the story, creating the pretense of reality; as narrator she explains that she has interviewed the people who knew Mona. But the film’s true affinities are with Miss Varda’s New Wave background and with the work of nouveau roman writers like Nathalie Sarraute, to whom she dedicates the film. As narrator-writer-director, Miss Varda self-consciously creates Mona. (”It seemed to me she came from the sea,” says the voice-over.) The scenario becomes a drama of images – the dark abandoned rooms where Mona hides, the brightly lit homes from which she’s excluded -that creates its own fragmented reality and invites the audience to envision it whole.

At times Miss Varda is jarringly blatant. The drab brown of the fields and roads Mona travels are set too abruptly against the maid’s peacock-blue clothes; characters face the camera or one another and declare they’ll never forget that disturbing woman. But ”Vagabond” is not doctrinaire (a charge often aimed at Miss Varda’s best-known work, the 1979 feminist film ”One Sings, the Other Doesn’t”). ”She’s free,” one character says of Mona. ”She scares me because she repels me,” says another. Such blunt statements do not set the film’s tone, but force us to ask whether Mona is a determined free spirit or just a lost soul.

Given a plot of land by the goatherd, she stays in a camper, refusing to clean or work. She moves in with a man who works in the vineyards and labors alongside him until her hands bleed, then turns on him accusingly when his colleagues force her out. Mona’s defensive anger shows her to be a captive of her own loneliness, and no matter how often we may want to shake this healthy, capable woman, we also feel enormous pity for her grim, stubborn existence.

Miss Bonnaire presents Mona’s inconsistencies with brilliant subtlety, her solemn eyes and stiff body capturing the tension of a life in which every meal, every night’s sleep becomes an ordeal. Late in the film, she gets drunk with an old woman, played by Marthe Jarnais, who captures the giggly, mischievous honesty that often surfaces in the elderly. But laughter can’t mask Mona’s illness or exhaustion. When we come full circle to her death, it carries the terrible weight of all we’ve seen.

Mona’s trials could be extended to all social misfits, but Miss Varda’s work is primarily about us as observers, uneasy with our helplessness and our detachment from a character whose outer life has been so relentlessly detailed yet whose thoughts remains buried. ”Vagabond,” which won the first prize at the Venice Film Festival and opens today at Lincoln Plaza 1, is so effective it can be grueling to sit through. But, reminiscent of Alain Renais, an early collaborator of hers, Agnes Varda has created a world too painfully real to ignore. Song of a Wayfarer VAGABOND, direction and screenplay (in French with English subtitles) by Agnes Varda; cinematography by Patrick Blossier; edited by Miss Varda and Patricia Mazuy; music by Joanna Bruzdowicz; produced by Cine-Tamaris, Films A2 with the participation of The French Ministry of Culture. At Lincoln Plaza 1, Broadway at 63d Street. Running time: 105 minutes.

This film has no rating.

http://www.nytimes.com/movie/review?res=9A0DE5D61E38F935A25756C0A960948260#h[]