Jeder stirbt für sich allein.qxp – Aufbau Verlag

Jeder stirbt für sich allein.qxp – Aufbau Verlag

Seul dans Berlin – Numilog

Hans FALLADA

Seul dans Berlin

Titre original :

Jeder stirbt für sich allein

Traduit par A. Vandevoorde et A. Virelle

Paru en 1947 en Allemagne

Puis en France chez Plon en 1967

Denoël, 2002 Gallimard (Folio), 2004

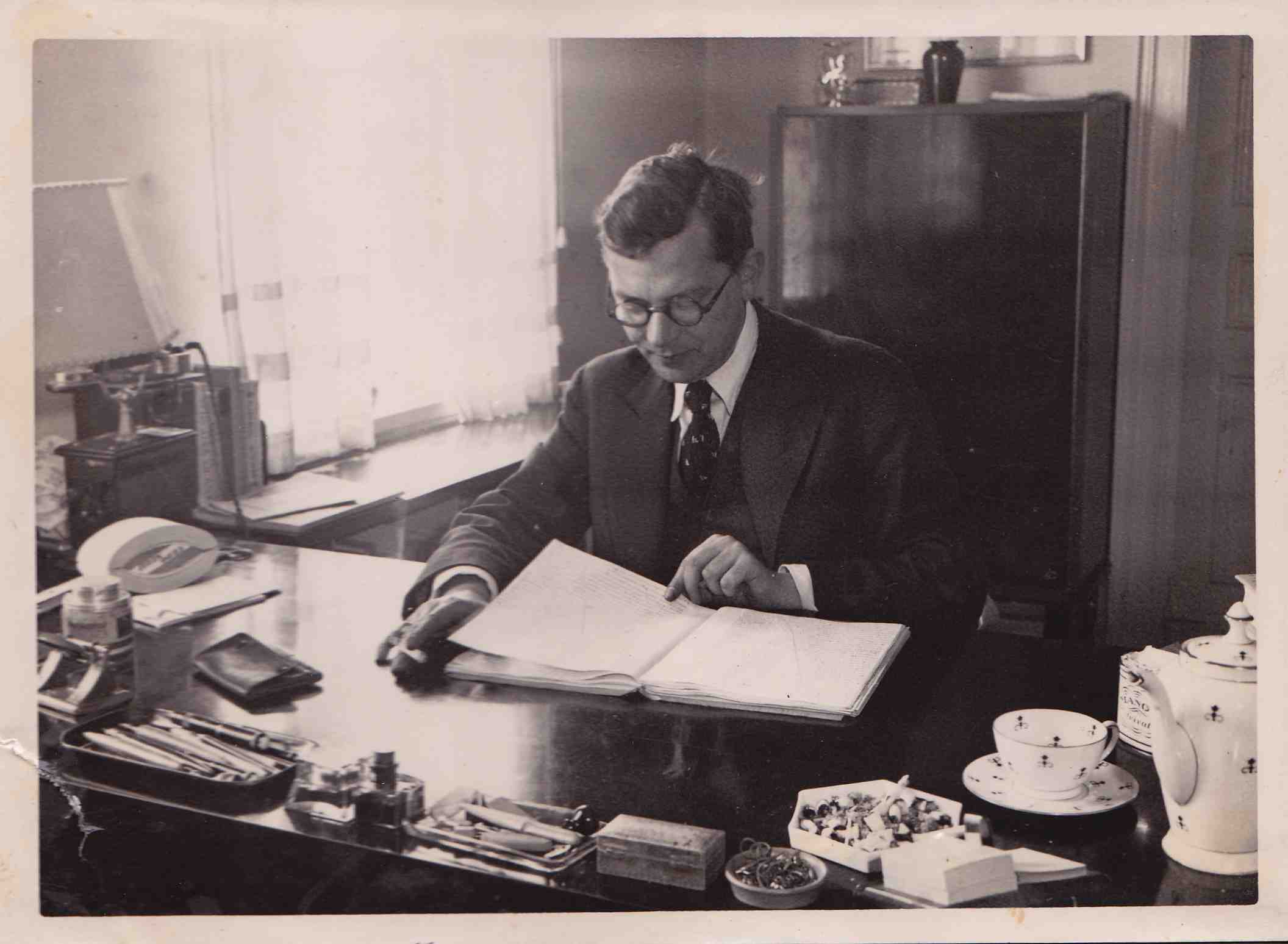

Hans Fallada

Seul dans Berlin, « l’un des plus beaux livres sur la résistance allemande antinazie » selon Primo Levi est le dernier roman d’Hans Fallada. Celui-ci, considéré comme l’un des plus grands écrivains allemands du XXe siècle, laisse une trentaine d’ouvrages derrière lui dont plusieurs sont traduits en français. Rudolf Ditzen dit Hans Fallada (ce pseudonyme fait référence à deux des personnages des contes des frères Grimm) est né en 1893 en Poméranie dans une famille aisée. En conflit avec son père dans son enfance, il est arrêté et interné dans une clinique psychiatrique à 18 ans après avoir tué son ami Hans Dietrich von Necker lors d’un duel. Il abandonne ses études et travaille successivement dans l’agriculture, l’édition et le journalisme tout en continuant d’écrire. Il mène une vie mouvementée et rencontre plusieurs problèmes. En effet ses succès littéraires vont être ponctués de cures de désintoxication et de séjours en prison.

Son premier succès a lieu en 1931 avec son roman Paysans, gros bonnets et bombes (Bauern, Bonzen und Bomben), puis l’année suivante Et puis après (Kleiner Mann, was nun ?) étend sa notoriété au-delà des frontières allemandes. L’auteur fait là une critique de la société allemande de l’entre-deux-guerres. Avec l’arrivée au pouvoir d’Hitler, Hans Fallada augmente sa production mais se consacre à une littérature plus distrayante que critique afin de bénéficier de la tolérance du régime nazi. Il écrit en 1944 Le buveur (Der Trinker), un roman qui rappelle le parcours de l’auteur dans lequel il évoque son parcours d’alcoolique et de morphinomane depuis sa jeunesse.

Hans Fallada dresse des romans fidèles de la société allemande de l’entre-deux-guerres en mettant en scène la vie des petites gens. C’est ce qui fait de Seul dans Berlin une œuvre de fiction romanesque assez plausible pour prendre aussi une valeur de témoignage.

Un roman

Ce roman, dont le titre original est « Chacun meurt seul », est fondé sur l’histoire réelle d’Otto et Elise Hampel, exécutés pour actes de résistance et dont le dossier de la Gestapo a été transmis à Hans Fallada après la guerre.

L’œuvre se divise en quatre parties. Dans la première, Hans Fallada semble construire assez lentement son roman avec une présentation bien ficelée des personnages et du contexte. Seul dans Berlin raconte la vie de gens ordinaires d’un immeuble dans Berlin, rue Jablonski au moment où les nazis fêtent leur victoire en France. Du sous-sol au troisième étage, et à travers les histoires des habitants de cet immeuble, Hans Fallada nous raconte comment tous ces personnages parviennent à vivre ou survivre sous le régime d’Hitler. On fait alors au fil des pages la rencontre avec Frau Rosenthal, une veuve juive, la famille Persicke, tous nazis convaincus, l’ancien magistrat Fromm, Emil Borkhausen, profiteur et voleur ainsi que le couple d’ouvriers Otto et Anna Quangel. C’est sur ce couple, plus précisément, que l’auteur se concentre. Mais d’autres personnages interviennent dans le roman tels que le commissaire Escherich de la Gestapo ou Eva Kluge, postière et membre du Parti qui va apporter la triste nouvelle de la mort de leur fils unique aux Quangel. C’est à partir de là que débute la dynamique romanesque car les Quangel, désespérés par la mort de leur fils vont décider de se lancer dans une lutte contre le nazisme et le Führer en écrivant des cartes postales de contre-propagande qu’ils vont abandonner dans les cages d’escalier des immeubles de Berlin. « En les voyant passer personne ne les soupçonnerait de disséminer régulièrement des cartes postales appelant les Allemands à la résistance dans des cages d’escaliers choisies au hasard… »

La seconde partie s’apparente à une enquête policière durant laquelle le commissaire Escherich est chargé de retrouver celui qui ose disséminer dans Berlin des messages qui insultent le IIIe Reich. Par ce biais nous découvrons les méthodes de la Gestapo : corruption, chantage violence… dans un cadre parfaitement hiérarchisé. L’enquête fonctionne selon l’effet papillon en ouvrant de multiples pistes au commissaire. Toutes s’avèrent fausses jusqu’au jour où les Quangel commettent une faute qui resserrera l’étau autour d’eux d’un seul coup. Fallada dépeint alors cette société dans laquelle priment l’égoïsme pour sauver sa peau, la folie normalisée où chacun a sa place et la peur. La peur de dire, de lâcher un mot, un nom de trop lors d’un banal interrogatoire de routine.

Enfin les troisième et quatrième parties érigent progressivement le couple en héros de la résistance antinazie bien qu’en réalité les cartes postales aient quasiment toutes atterri à la Gestapo sans avoir été lues par ceux qui les ont ramassées tant la peur de la répression était forte. Quangel et sa femme sont évidemment condamnés, lui à la peine capitale et elle à la prison. Les fréquentations des Quangel sont aussi arrêtées et certaines exécutées. Mais cet acte de résistance finalement inutile mettra toutefois en valeur d’autres types de résistances à travers par exemple le conseiller Fromm qui héberge des juifs ou Eva Kluge qui adopte le fils abandonné de Borkmann. C’est ici l’héroïsme que Fallada a voulu mettre en valeur, de personnes qui en temps normal seraient des individus ordinaires et qui en temps de troubles ont choisi de résister.

« – … Vous avez résisté au mal, vous et tous ceux qui sont dans cette prison. Et les autres détenus, et les dizaines de milliers des camps de concentration… Tous résistent aujourd’hui et ils résisteront demain.

– Oui et ensuite, on nous fera disparaître ! Et à quoi aura servi notre résistance ?

– A nous, elle aura beaucoup servi, car nous pourrons nous sentir purs jusqu’à la mort. Et plus encore au peuple, qui sera sauvé à cause de quelques justes, comme il est écrit dans la Bible. Voyez-vous Quangel, il aurait naturellement été cent fois préférable que nous ayons eu quelqu’un pour nous dire : ” Voilà comment vous devez agir. Voilà quel est notre plan. ” Mais s’il avait existé en Allemagne un homme capable de dire cela, nous n’aurions pas eu 1933. Il a donc fallu que nous agissions isolément. Mais cela ne signifie pas que nous sommes seuls et nous finirons par vaincre. Rien n’est inutile en ce monde. »

Un témoignage

Ce roman permet de se représenter la réalité de la vie à Berlin pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Le style est littéraire et les descriptions précises, notamment dans l’évocation du fonctionnement de la police de l’époque. Fallada écrit avec réalisme et parvient à suggérer l’inquiétude et l’angoisse, à créer une atmosphère qui rend la fiction suffisamment plausible pour qu’elle puisse prendre une valeur de témoignage. En effet, ce roman social dépeint des péripéties dramatiques qui incitent à se laisser captiver, des moments plus drôles lorsque Borkhausen se prend lui-même à ses propres entourloupes, ainsi qu’un certain suspense pour savoir si oui ou non la Gestapo va finir par arrêter les Quangel. Le climat et les mentalités sont habilement rendus. Mais Fallada essaye de rendre également compte des délations, des menaces, des chantages et des pressions qui ont fait le quotidien des habitants berlinois sous le IIIe Reich.

Ce roman donne à comprendre de l’intérieur comment a fonctionné le régime nazi et l’immeuble de la rue Jablonski devient à lui seul un échantillon représentatif de tous les comportements qui ont pu exister durant cette période. Il n’y a aucun héros ni coup d’éclat dans cette histoire, puisque même les Quangel entrent en résistance en tant que simples gens plutôt pour se venger de la mort de leur fils que par réelle idéologie. L’auteur est témoin de l’intérieur et décrit l’engrenage des comportements face à la peur d’où découlent plusieurs attitudes possibles : la résistance, la lâcheté, la collaboration, la passivité, la délation, la paranoïa… Chacun s’observe, se jauge, à la limite du défi. Quel comportement adopter lorsque la terreur nous ronge en permanence ? Cet aspect moral met à nu l’âme humaine. La plupart du temps c’est l’égoïsme qui gagne et Fallada n’essaye pas de la cacher. Cependant il a voulu mettre en avant l’héroïsme de quelques-uns qui à travers leurs petits actes ont participé à leur façon à la chute de l’Empire d’Hitler.

En filigrane, Fallada se pose la question de savoir pourquoi la résistance ne s’est pas organisée en Allemagne sur une échelle comparable à celle des autres pays. En France, quand on luttait contre les nazis, on était un résistant à l’ennemi. En Allemagne, quand on faisait la même chose, on était un traître à la nation. L’auteur met cela sur le compte tout d’abord du lien puissant qui lie l’Allemand de l’époque au pouvoir et de la discipline germanique, puis sur celui de la lâcheté qui a affligé Borkhausen notamment, le désir de vivre même si cela doit en coûter aux autres.

Élisa Langdorf, 1ère année édition/librairie

http://littexpress.over-blog.net/article-hans-fallada-seul-dans-berlin-76498211.html

Karl Radek parle de Hans Fallada (1934)

Congrès des écrivains soviétiques – 1934

Karl Radek :

La littérature mondiale contemporaine

et les tâches de l’art prolétarien

[extraits]

Discours:prononcé en août 1934.

Source:Gorky, Radek, Bukharin, Zhdanov and others, Soviet Writers’ Congress 1934, pp.73-182, Lawrence & Wishart, 1977;

Online Version:Marxists Internet Archive (marxists.org) 2004;

Transcrit par :Andy Blunden pour les Marxists Internet Archive.

Traduction : Alain C. (septembre 2011)

[….]

5. Fascisme et littérature

Nous, le Congrès des écrivains soviétiques, tendons une main fraternelle à tous les écrivains qui cheminent vers nous, aussi loin de nous soient-ils pour le moment, si nous voyons seulement en eux la volonté et le désir de venir en aide à la classe ouvrière dans sa lutte, de venir en aide à l’Union Soviétique.

Nous leur disons : le meilleur service que vous puissiez nous rendre est de vous tenir épaule contre épaule avec la classe ouvrière dans vos propres pays, avec sa minorité révolutionnaire, prêt à lutter contre tous ces dangers qui ont banni le sommeil de vos nuits, qui ont dissipé votre calme esthétique. Les écrivains qui ne saisissent pas ce fait finiront inévitablement par atterrir dans le camp du fascisme, et il est donc d’une importance suprême que, nous et vous, puissions considérer ensemble la question : que signifie le fascisme pour la littérature ? Nos écrivains révolutionnaires ont une grande tâche devant eux – celle d’étudier, complètement et en détail, le destin de la littérature sous le règne du fascisme. Occupé comme nous le sommes par la lutte politique, d’abord et avant tout, nous n’avons pas consacré assez de temps et d’attention à cette tâche ; néanmoins l’histoire du destin de la littérature sous le sceptre fasciste constitue l’avertissement gravissime, un « dernier avertissement » pour tous les écrivains.

Les écrivains devraient s’interroger eux-mêmes – et devraient répondre à la question – que signifie le fascisme pour la culture, la littérature ? Je ne vais pas ici refaire le récit de l’histoire de l’attitude prise par le fascisme italien ou allemand face aux problèmes fondamentaux de la science, ou démontrer l’aspect mystique et irrationnel, l’aspect médiéval du fascisme. Je ne vais traiter ici que de la question de cette attitude envers la littérature – vous vous souviendrez quel hurlement fut celui de toute la littérature mondiale lorsqu’elle appris quelle vision de la littérature avaient les Marxistes, les bolchéviques, qui affirmaient que la littérature est une arme sociale, qu’elle est l’expression de la lutte des classes. Pour les esthètes, pour les représentants de la littérature internationale, ceci ressembla à une monstrueuse invention des Bolchéviques. Notre conception d’écrivains qui doivent servir la cause des classes opprimées dans leur lutte apparu à ces esthètes comme un rabaissement blasphématoire de la littérature, depuis les hauteurs intellectuelles de l’art vers le rôle de servante de l’histoire. Les fascistes, représentés par leurs théoriciens et leaders de l’art, disent : « Il ne peut y avoir de littérature qui se tienne à l’écart de la lutte. Vous êtes ou bien avec nous ou bien contre nous. Si vous vous rangez à nos côtés, alors écrivez selon le point de vue de notre philosophie; et si vous n’êtes pas de notre côté, alors votre place est en camp de concentration. » Goebbels a dit cela des centaines de fois. Rosenberg a proclamé cela des centaines de fois.

Il est un écrivain allemand, Hans Fallada, fort talentueux, dont le livre, Kleiner Mann – Was Nun ?, est bien connu dans notre pays. Hans Fallada dépeint merveilleusement les souffrances des masses au sein de la société bourgeoise, montre comment elles sont dupées par les représentants du capitalisme, par les représentants de la démocratie bourgeoise. Il a décrit les Sociaux-démocrates, les fascistes… Mais beaucoup ont eu des difficultés à déterminer s’il était pour les fascistes ou contre eux. La figure principale de son livre est un petit employé de bureau honnête que la crise a jeté à la rue, un homme qui peut à peine rester entier – corps et âme – et n’a plus assez de forces pour combattre.

Hans Fallada a maintenant écrit un nouveau roman, Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst. Le héros de ce roman est un petit-bourgeois « déchu » qui a atterri en prison et y purge une peine de cinq ans. Il essaye de se racheter, de vivre comme un honnête citoyen, mais la machine bureaucratique bourgeoise du capitalisme le ramène tout droit en prison. Et quand son héros atterri une fois de plus en prison, il a comme le sentiment d’être retourné auprès de sa propre mère. Maintenant il a devant lui une condamnation pour quinze ans, mais il n’éprouve plus le besoin de lutter…

C’est un livre fort talentueux, mais désespéré. Il a paru alors qu’Hitler était déjà au pouvoir. Dans son avant-propos, Hans Fallada écrit que l’image qu’il a dessiné se réfère au passé, que les fascistes vont créer de nouvelles conditions. Il décida, de cette façon, de sauvegarder le livre et lui-même, prétendant qu’il ne parlait que du passé.

Mais comment les fascistes ont-ils répondu à cela ? Le Börsenzeitung de Berlin a publié un article fulminant au contenu suivanti :

« Nous savons que Hans Fallada n’a pas écrit ce livre contre nous. Qu’il essaye seulement ! Mais de qui a-t-il pris la défense dans ce livre ? Il a écrit en défense des ratés, de ceux que l’histoire a réduit en poussière. Il a éveillé de la pitié pour ceux qui devraient disparaître pour faire place aux troupes d’assauts avec leurs muscles et leurs revolvers en main. »

Le fascisme, qui trahit les intérêts de la petite bourgeoisie, sait que lorsque les gens liront ce livre, montrant comme il le fait de quelle façon le capitalisme a réduit en poussière la petite bourgeoisie sous le système démocratique, ils diront : « Sous les fascistes ce n’est pas mieux mais pire. » Et les fascistes demandent à l’écrivain : « Dessinez-nous une vision montrant comment, sous le fascisme, les gens progressent, se développent et prospèrent. Ne vous avisez pas d’éveiller la pitié pour ceux que le capitalisme a réduit en poussière. »

Nous ne savons pas ce que le petit homme, Hans Fallada, dira, que sera son destin maintenant, où il ira se réfugier. Le fascisme lui dit : « Il n’y a pas de zones neutres. Ecrivez comme on vous le demande ou vous serez détruit. » Les passages cités ci-dessus de deux pièces de Bernard Shaw ne font pas exception. Ils représentent seulement une expression plus frappante du fait que la critique de la civilisation capitaliste, la critique de la civilisation bourgeoise, en un seul et même temps, la première étape dans l’évolution de l’artiste vers le socialisme révolutionnaire et aussi la première étape de son évolution vers le fascisme. Il suffit de mentionner de productions littéraires comme Union der festen Hand de Reger, les romans de von Salomon – pour prendre des exemples dans la littérature allemande – ou de mentionner ces œuvres de la littérature française qui traitent de la corruption parlementaire, pour voir que le point qui pose problème est le dilemme de l’écrivain face à la solution socialiste-révolutionnaire à la crise du capitalisme et la pseudo-solution fasciste à cette crise. Il suffit de mentionner que les livres de Fallada ont donné lieu a une discussion assidue pour savoir s’ils sont révolutionnaires ou fascistes.

Ceci est arrivé à une époque où le fascisme était déjà au pouvoir en Italie depuis près de dix ans, à une époque où les gouvernements fascistes ou semi-fascistes dans plusieurs pays avaient déjà révélé le vrai visage du fascisme à tous ceux qui avaient souhaité le voir. Et dans tous ces romans, le pont menant au fascisme empêcha d’évaluer le rôle du prolétariat, ne permis pas d’observer le début de son combat révolutionnaire. La critique des résultats de la culture capitaliste a servi par le passé et, dans le cas de nombreux écrivains petits bourgeois, sert encore aujourd’hui de tremplin au fascisme. Ceci peut se produire de deux façons : ou bien l’écrivain nourrit l’illusion que le fascisme va effectuer la purification de la civilisation moderne, qu’il représente une médecine cruelle mais cependant une médecine ; ou bien il soutient qu’il n’y a aucune puissance qui puisse empêcher la victoire du fascisme. Hautement caractéristique à ce sujet est la réponse donnée par le célèbre écrivain français, Céline, auteur du très discuté roman, Voyage au bout de la nuit.

Céline a peint un tableau effrayant, nos seulement de la France d’aujourd’hui, mais de tout le monde contemporain. Il a vu les abysses de la guerre. Il a plongé dans le cloaque de la politique coloniale. Il a tourné son regard vers la « prospérité » américaine. Il a décrit une description sombre de la petite bourgeoisie française.

Dans le monde entier le seul personnage humain qu’il ai pu trouver était une prostituée. Et après tout cela, en réponse à un questionnaire d’un magasine au sujet du danger du fascisme, il dit :

« Dictature ? Pourquoi pas ! Il ferait beau voir qu’on n’en est pas capable aussi ! Défense contre le fascisme ? Vous voulez rigoler, vous n’avez pas été à la guerre, Mademoiselle, ça se sent vous voyez à des questions pareilles. Quand le militaire prend le commandement, Mademoiselle, il n’y a plus de résistances, on ne résiste pas au Dionosaure [sic]. Il crève de lui-même – et nous avec – dans son ventre, Mademoiselle, dans son ventre. » (1)

Pour celui qui entretient une telle opinion sur la force du fascisme et l’inéluctabilité de sa victoire, la lutte contre le fascisme est impossible, la soumission inévitable. Aussi la question de savoir si l’écrivain, dans le ventre du fascisme victorieux va gagner son pain en cirant les bottes, ou s’il va s’y adapter et commencer à chercher une justification à l’inévitable, c’est-à-dire à le servir, est une question d’importance secondaire.

[…]

(1) Nous citons d’après le texte publié dans Cahiers Céline 7. Céline et l’actualité 1933-1961. Gallimard, Paris 1986. (p. 18)

http://etpuisapres.hautetfort.com/archive/2011/09/10/karl-radek-parle-de-hans-fallada-1934.html

5. Fascism and Literature

We, the Congress of Soviet Writers, stretch out the hand of brotherhood to all writers who are on the Way to us, however far from us they may be as yet, if only we see in them the will and the desire to help the working class in its struggle, to help the Soviet Union. We tell them: The best help you can render us is to stand shoulder to shoulder with the working class in your own countries, with its revolutionary minority, ready to struggle against all those dangers which have banished the sleep from your eyes, which have dispelled your aesthetic quiet. Writers who do not grasp this fact will inevitably land up in the camp of fascism, and it is therefore of supreme importance that we and you should jointly consider the question: What does fascism mean for literature? Our revolutionary writers have a great task before them – that of studying, fully and specifically, the fate of literature under the rule of fascism. Occupied as we are with the political struggle first and foremost, we have not devoted enough time and attention to this task; nevertheless, the history of the fate of literature under the fascist sceptre constitutes the very gravest warning, the “writing on the wall” for all writers.

Writers should ask themselves – and should answer the question – what does fascism mean for culture, for literature? I will not here recount the history of the attitude taken by Italian and German fascism to the fundamental problems of science, or demonstrate the, mystical and irrational aspect, the medieval aspect of fascism. I will deal only with the question of its attitude to literature – You will remember how all world literature set up a howl when it learned of the views on literature held by the Marxists, by the Bolsheviks, who assert that literature is a social weapon, that it expresses the struggle of classes. To the aesthetes, to the representatives of world literature, this seemed a monstrous invention of the Bolsheviks. Our conception of writers who ought to serve the cause of the oppressed classes in their struggle seemed to these aesthetes to he a blasphemous abasement of literature from the intellectual heights of art to the post of handmaiden of history. The fascists, as represented by their theoreticians and leaders of art, say: “There can be no literature standing aloof from the struggle. Either you go with us or against us. If you side with us, then write from the viewpoint of our philosophy; and if you do not side with us, then your place is in the concentration camp.” Göbbels has said this hundreds of times. Rosenherg has proclaimed this hundreds of times.

There is a very talented German writer, Hans Fallada, whose book, Little Man, What Now?, is well-known in our country. Hans Fallada splendidly portrays the sufferings of the masses in bourgeois society, shows how they are duped by the representatives of capitalism, by the representatives of bourgeois democracy. He has depicted the Social-Democrats, the fascists. But many have found it difficult to determine whether he is for the fascists or against them. The chief figure in his book is an honest little office worker whom the crisis has thrown out on the street, a man who can only just keep body – and soul – together and has no strength left to fight.

Hans Fallada has now written a new novel, Wer einmal aus dem Blechnapf frisst. The hero of this novel is a “fallen” petty bourgeois who has landed in jail and served a sentence of five years. He tries to get on his feet again, to live like an honest citizen, but the bureaucratic bourgeois machine of capitalism drags him back to prison. And when this hero finally lands up once again in jail, he feels as though he had returned to his own mother. Now he has a sentence of fifteen years before him, but there is no more need for him to struggle …

This is a very talented book, but a hopeless one. It appeared when Hitler had already come to power. In his foreword Hans Fallada writes that the picture he has drawn refers to the past, that the fascists will create new conditions. He decided in this way to save both the book and himself, pretending that he was speaking only of the past.

But how did the fascists answer this? The Berlin Börsenzeitung published a fulminating article of the following content:

“We know that Hans Fallada did not write this book against us. Let him just try! But whom did he defend in this book? He wrote it in defence of failures, of those whom history has ground to powder. He awakens pity for those who must be removed from life in order to leave room for Storm Troopers with muscles and revolvers in their hands.”

Fascism, which betrays the interests of the petty bourgeoisie, knows that when people read this book, showing as it does how capitalism has. ground the petty bourgeoisie to powder under the democratic system, they will say: “Under the fascists it’s not better but worse.” And the fascists. demand of the writer: “You draw us a picture showing how under fascism everybody is advancing, developing and prospering. Don’t you dare to awaken pity for those whom capitalism grinds to powder.”

We do not know what the little man, Hans Fallada, will say, what his fate will be now, where he will hide. Fascism tells him: “There are no neutral zones. Write as we demand, or you will be destroyed.” The passages quoted above from Bernard Shaw’s two plays are no exception. They represent only. a more striking expression of the fact that criticism of capitalist civilization, criticism of bourgeois democracy, may become at one and the same time the first step in the artist’s evolution towards revolutionary socialism and also the first step in his evolution towards fascism. It is sufficient to mention such literary productions as Reger’s Union der festen Hand, the novels of von Salomon – to choose some examples from German literature – or to mention those works of French literature which expose parliamentary corruption, in order to see that the point at issue is the dilemma of the writer between the revolutionary solution of the crisis of capitalism and the fascist pseudo-solution of this crisis. It is sufficient to mention that Fallada’s books have given rise to a regular discussion as to whether they are revolutionary or fascist.

This happened at a time when fascism had already been ruling in Italy for nearly ten years, at a time when the fascist and semi-fascist governments in several countries had already disclosed the true face of fascism for all who wished to see it. And in all these novels the bridge leading to fascism was failure to appraise the role of the proletariat, reluctance to observe the beginning of its revolutionary struggle. Criticism of the results of capitalist culture has served in the past and, in the case of many petty-bourgeois writers, is still serving today as the springboard to fascism. This may happen in two ways: either the writer cherishes the illusion that fascism will effect the purification of modern civilization, that it represents a cruel medicine but still a medicine; or he may hold that there is no power which can stop the victory of fascism. Highly characteristic in this respect is the answer given by the well-known French writer, Céline, author of the much discussed novel, Journey to the End of the Night.

Céline has painted a frightful picture, not only of present-day France, but of the whole contemporary world. He looked into the abyss of war. He looked into the cesspool of colonial politics. He turned his gaze upon American “prosperity.” He penned a dismal description of the French petty bourgeoisie.

In the whole world the only human character whom he could find was a prostitute. And after all this, in answer to a questionnaire from a magazine regarding the danger of fascism, he said:

“Dictatorship? Why not! It would be good to have a look at … Defence against fascism? You are jesting, mademoiselle! You were not in the war – this can be felt, you know, from such questions … When a military man takes command, mademoiselle, resistance is impossible. One does not resist a dinosaur, mademoiselle. It croaks of itself, and we together with it, in its belly, mademoiselle, in its belly.”

To one who entertains such an opinion of the strength of fascism and the inevitability of its victory, struggle against it is impossible, submission unavoidable. Then the question of whether the writer, in the belly of victorious fascism, will earn his bread by blacking boots, or whether he will adapt himself to it and begin to seek. a justification for the inevitable, i.e., to serve it, is a question of secondary importance.

January 30, 1933 – the date when the German fascists came to power – and the March days of 1933, when German and world literature was consigned to the bonfire on the square before the University of Berlin – this was the last test which the world set bourgeois literature, this was the last challenge issued to it by history.

The World War descended upon the head of humanity like a rain of fire. Bourgeois literature continued to serve the bourgeoisie. October 1917 saw how the earth was opening, and the capitalist world began to quake beneath. the feet of world literature, but it, “the salt of the earth,” not only failed to point the way to mankind, but could not even grasp what was taking place. It needed the putrefaction of post-war capitalism, it needed the harsh lessons of the world crisis, before a part of present-day literature began to use its brains and to conceive that something had finally collapsed into the past, that something new had arisen.

The great majority of writers remained essentially on the side of the bourgeoisie, screening themselves behind empty phrases to the effect that “politics did not concern them.” Fascism, as represented by the German Nazis with their bonfires of books, has now planted its foot upon the breast of literature. Hundreds, if not thousands, of writers have been obliged to flee from Germany as from an earthquake, leaving their books for the hangman to destroy. They. are pursued by the frenzied cries of the high priests of German fascism:

“Back to earth and blood! Away from the culture of man kind! It does not exist at all, just as world history does not exist – there is only the history of separate nations. Its contents are the struggle of man against man, of god against god, of character against character.” (From a speech by Rosenherg.)

“The personality of the artist.” Rosenherg has declared, “should develop freely, without restraint. One thing, however, we demand – acknowledgment of our creed. Only he who accepts this is worthy to enter the struggle. No idylls! Firmness and iron staunchness! … Artists and writers are those whom we recognize as such, they are those whom we call upon for this purpose.”

The charge which Göbbels has levelled at art is that “it did not see the people, did not see the community, did not feel any bond with it; it has lived alongside of the epoch and behind the people; it could not therefore reflect the spiritual experiences of this epoch and the problems that agitate, it, and only expressed surprise when time passed it by without paying attention to literary researches and experiments. When complaints were raised – that the people was not connected with art, this was said by those same persons who had severed the connection between art and the people.” And, declaring that “the revolution is not stopping anywhere, it is winning over the people and society, it is setting its stamp upon economy, politics and private life – whereby he christened fascist counter-revolution with the name of revolution – Göbbels uttered the following threat to literature: “It would be naive to suppose that the revolution will spare art, that the latter will be able to lead its form of existence as a sleeping beauty somewhere alongside of the epoch or in its backyards. In this condition of sleep, art proclaims: ‘Art stands above parties, it is international; the tasks of art are higher than those of politics. We artists are outside politics, politics are detrimental to the character.”

Göbbels declares that this might have been permissible in the past, when politics reduced themselves to parliamentary squabbles, but when fascism came to power, – at that moment when politics become a national drama in which whole worlds tumbled to the ground, the artist cannot say: “This does not concern me.” It concerns him very much indeed. And if he lets slip the moment at which his art should take a definite stand in regard to the new principles, then he should not be surprised if life goes roaring past him.” Göbbels proclaims that “art should hold to definite standards in regard to morals, politics and views of life – standards which are set up once and for all.”

When the proletarian revolution reminded artists of the elementary truth that they are members of society, that their work is therefore rooted in society and, consciously or unconsciously, expresses the aspirations of some class or other, when the proletarian revolution called upon artists to side consciously with the proletariat, the overwhelming majority of them answered: “Leave us alone in peace.” They answered by referring to the non-political character of the artist, and regarded the proletarian revolution as a horde of vandals, breaking into the temple of art in order to destroy it. Now it is counter-revolution which, taking its cue from revolution, turns to art and says: “This is a fight to the death, and In the battle there can be no neutrals – either for us or against us.” Burning books on the squares of Berlin, fascism says to world literature: “Make your choice.”

And we see how throughout the whole world, the fixing of boundaries is beginning. We see how even in England, America, France, fascist tendencies are springing up in literature, how artists are rehearsing for the role of conscious instruments of the dictatorship of monopoly capital. The fact that the English literary magazine, The Criterion, has begun to speak in fascist tones, the fascist declarations of the English poet T.S. Eliot, the fact that fascist tendencies in American literature are beginning to crystallize, the statement of a well-known American critic to the effect that “if we are to speak of parties, then fascism, of course, can offer more than communism,” and that “of all the many forms of emotional and intellectual influence, patriotism is the sole means capable of restoring to the artist and critic their contact with the reading public and with their environment,” the rise of a number of fascist organs among the French literary youth – all these things are “signs of the time.” Even in those countries where fascism has not conquered, that No-Man’s-Land upon which the allegedly non-political writer can maintain himself is growing more contracted. The literary ‘world is forced to. choose between the revolution of the proletariat and the preventive counter-revolution of monopoly capital.

It need hardly he said that before making this choice one should first be clear as to what end fascism is serving and whom the artist wishes to serve. Fascism is the power of the magnates of iron, of coal, of the exchange, who subject the proletariat to their rule with fire and sword, who are preparing for a new world war and who rely for support upon the duped masses of the petty bourgeoisie. However much fascism may seek to camouflage itself with “Left” tendencies, with social demagogy, it is none the less the rule of the bandits of monopoly capitalism.

Nay, more: even if a dictatorial bourgeois government were formed with the aim of preventing the triumph of fascism – and the semi-fascist – wing of the French radicals is playing with this idea, as are also the representatives of the “brain trust” in America – this represents nothing but deception and self-deceit. Dictatorial power cannot exist if it is not based on a powerful class force. If it hinds the working class hand and foot, it thereby unbinds the hands of the monopoly bourgeoisie. And the revolutionary French writer, Jean-Richard Bloch, is a hundred times right when he says in his answer to a newspaper questionnaire:

“In democratic countries the way is opened for fascism by the ‘law granting plenary powers.’ The passing of such laws is best secured by Left governments, which find them necessary. When, however, the usual swing of the see-saw of parliamentary politics brings a party of social reaction into power, these laws are there, ready for such a party to make use of them.”

There are no middle positions, there is no “Left” fascism, having the alleged aim of defending democracy and the masses. There is either proletarian revolution or fascism. In making his choice, the writer will he deciding not only the question of his place in the coming struggle, but also that of the fate of literature, the fate of art.

Meanwhile German fascism is busily destroying that art upon which Germany used to plume herself before the entire world. It advances, in the capacity of its writers, individuals devoid of talent, who can only utter cries of “land, blood, the nation” – persons of the type of Johst and Beumelburg. It might perhaps plead in its defence that it has only been in power for a year and a half. But it is sufficient to examine the development of Italian literature during the ten years of fascism’s existence in order to see that fascism mean’s death to literature and art. The older Italian writers who have lived on under fascism, such as D’Annunzio, Pirandello, Papini, are almost silent, or else publish only weak productions, which show that the authors have outlived their day. There is nothing to be surprised at in this. What coherence can there be in Pirandello, the meaning of whose work the Italian critic Adriano Tilgher has correctly defined as “The tragedy of impotence and longing for initiative life.” All Pirandello’s work has frankly reflected the downfall of the bourgeoisie., his masks and marionettes, by which he tries to break up reality into a number of mutually mocking ‘contradictions, are obliged to be silent when confronted with fascism, which claims to hold. in its hands the solution to all world problems.

An artist like Corrado Alvaro, who still possesses some significance from the point of view of art, stands aloof from the realities of Italian life. The proscenium of the Italian literary stage is occupied by the producers of light reading matter, such as D’Ambra, Brocchi, Varaldo, or by dealers in pornography, like Verona, Pitigrilli, Mura – such is the opinion of Rank, the German historian of post-war Italian literature.

This fact is admitted by the fascists themselves, Ercole Rivalta writes as follows in the Giornale d’Italia:

“Literature depicts Italian youth as abandoned to vicious instincts, devoid of the least gleam of spirituality, a slave to animal lusts. And this represents, not literary fantasy, but profound reality, embodied in people who, having been born in the first decade of the century and not having been through all the horrors of war, have not accomplished great deeds, have not fought for the fascist revolution, but are the incarnation of chaotic triviality. We must stop the mouths of these homunculi without more ado.”

Just imagine us telling one of our YCLers that he is not accomplishing great deeds, that he is a worthless “homunculus” because, having been born too late, he did not take part in the October Revolution.

We know that our YCLers are the pride of our country, that all the great construction works are YCL works. Anyone who has been on our great construction jobs will have seen that YCLers are working everywhere – from workers at the bench to engineers. Our YCL is accomplishing great deeds. But of the fascist youth who have grown up after the fascists came to power, the Giornale d’Italia writes that they are homunculi who have not accomplished great deeds.

Gherardo Casini, editor of Lavoro Fascista, writes as follows in Critica Fascista:

“The, main historical and political question is: How in a fervid, triumphant period of revolution, can a literature exist which obstinately tries to shut itself up within the most limited bounds, repudiating all renovation? We must breathe into literature a stream of new life, make it take part in, the building of new history.”

Telesio Interlandi, editor of Tevere, wails:

“We need a writer who will see our villages gay, our peasants joyful, our workers calm, trustful and reconciled to the fatherland, who will see how our roads, radiating out from Rome, stretch to all corners of the world, who will hear the metallic voice of Mussolini filling the squares.”

And the unfortunate fascist writers battle with the task assigned them: they depict Italy as she is not.

In his Fascist Stories, Dario Lischi describes a brave fascist officer who – though somewhat reminiscent of Falstaff – is none the less a doer of good deeds, while the villain of the piece, a Bolshevik, is portrayed as a criminal.

Orsini Ratto tells in his Love Fourfold how the hero, having tried a number of women, ultimately finds satisfaction in fascism, acquires wealth, travels around the world, is ruined only to get rich again and founds a philanthropical institute in the fascist province of Tripoli.

The hero of a third fascist novelist, Donato, had already fallen into complete despair and would most probably have perished to no purpose, had not the spectacle of a fascist demonstration reawakened his love of life.

Albatrelli in his book Conquistadors describes how a peasant movement was broken up by a number of devout fascists.

Finally, Mario Carli, in the novel An Italian of the Times of Mussolini – a book which was awarded the Labia Prize and which was published under the auspices of Mussolini himself – has tried to give a picture of the realization of the fascist program. And what is the gist of it? An old aristocrat, representing the old Italy, does not want to develop agriculture by modern methods. The son – a fascist, close to Mussolini – tries to persuade his father, and secures the aid of an old uncle, who has returned to Italy after acquiring a fortune in America. But it is all to no purpose; and when the wicked old aristocrat refuses, even with the financial aid of his American brother, to develop Italian agriculture and thus free Italy from dependence upon foreign agriculture, Mussolini decrees that the parasitic aristocrat be deprived of his estates and that they be placed under state control, and hands over the administration of the estates to the land-owner’s son – the fascist.

For, as Carli writes, “rights of property exist and will be preserved so long as the owner does not violate those obligations which are inalienable from them; but when he forgets the obligations, his rights will vanish” – and be transferred to his son, we might add.

This image may prove inspiring to the fascist sons of prodigal fathers. But why should it inspire the reader and the writer? The reader and the writer are evidently intended to feel satisfaction at what the hero of the novel tells his uncle after the latter’s arrival from America: “Naples, you see, used to be dirty, but now it’s clean, and the beggars have been removed from the streets.”

However, if all this proves insufficiently inspiring to the reader, the following piece of rant on the subject of war may fairly be expected to strike home:

“War represents a really valuable phenomenon, for it compels all people to make the choice between courage and cowardice, between self-sacrifice and egoism, between inner experience and pure materialism. It is, of course, a rude phenomenon – man against man, character against character, nerves against nerves; but this phenomenon divides the hysterical folk, the worms, the whiners, the spoilt children from the courageous, wise idealists, from the mystics of dangers, from the heroes of blood.”

The fascist heroes of blood are persons who sacrifice the blood of others with supreme facility, and it may he that rant has an inspiring effect upon them. Among the masses of the people, who will have to shed their blood on behalf of Italian fascism, this rant will probably arouse nothing but a feeling of disgust. The fascist writers are aware of this, which is why this rant sounds so unconvincing and why their art is so lifeless, so febrile.

Let us take a glance at Polish literature. For one hundred and fifty years Poland was torn asunder by three conquerors. In bondage, she created one of the most brilliant literatures in the world. One might have expected that national unification would usher in a golden age of Polish literature. And she does possess some very talented writers even now. But the greatest Polish writer of our day, Zeromski, Went to the grave with the question on his lips – the question which forms the core of his Early Spring: Was it for this Poland that we fought? The most outstanding writer of the fascist tendency now ruling in Poland, the staunch adherent of Pilsudski, Kaden-Bandrowski, is attempting to give a picture of contemporary Poland in a series of novels.

In the first part of his trilogy he depicts the decline of Polish capitalism, the treachery of the parties of the Second International. He endeavoured to represent communism as a movement of helpless though honest workers, but he did not dare to show the Polish fascists in the setting of Poland’s main coal area. In the second part of his trilogy he has portrayed the corruption and decay of the young Polish parliamentary system – the party of the Polish kulaks, the party of the Polish aristocrats, the party of the Polish socialists, who. have betrayed the workers. But although he brings down his story almost to the moment of Pilsudski’s final advent – to power, he has not portrayed the followers of Pilsudski, the representatives of the Polish form of fascism. He did not portray them, because he was afraid to do so, because the face of Polish fascism is too unattractive for a great artist to dare to show it and to convince the reader that fascism is a blessing. Kaden’s talent comes into conflict with his political convictions.

We must answer the question – and this represents the basic question from the point of view of literature – why literature is dying out under fascism. This does not mean that a talented fascist writer cannot make his appearance. But there has not been and will not be a fascist literature capable of convincing the millions.

Fascism means the end of great literature; by the logic of its own inner laws it means the decay of literature. Why? The reason for this is perfectly clear. It is connected with the very roots of literature and art. In the period when slave-owning society was flourishing, when the culture of the ancient world was arising on its basis, Aeschylus, Sophocles, Aristotle. and the rest did not perceive any cracks in the foundations of this slave-owning society. They believed it to be the only possible and rational form of society, and were therefore able to create their works without feeling any twinges of doubt. Men feudalism represented the only possible organization of society, it was possible for great feudal poets to exist.

But when, in the days when serfdom was already declining, Gogol defended it in his Letters To Friends, Belinsky spat in the face of the great poet, and everything which made for the creation of great Russian literature was on’ Belinsky’s side. Serfdom could not find advocacy in great works of art because it was already dying, because it was corroded with the worms of capitalist development, because abroad there already existed a society freed from serfdom, and the intelligence, the conscience of an artist could not any longer defend a perishing system, doomed by history.

In the period when capitalism was flourishing, when it was the bearer of progress, it could have its bards, and these bards, in creating their works, knew and believed that they would find an echo among hundreds of thousands and millions of people who regarded capitalism as a good thing.

We should ask ourselves the following question: Why was there a Shakespeare in the sixteenth century, and why is the bourgeoisie today unable to produce a Shakespeare? Why were there great writers in the eighteenth century and in the beginning of the nineteenth? Why are there no such great. writers today as Goethe, Schiller, Byron, Heine, or even Victor Hugo? The literature of the bourgeois period has always been bourgeois literature; it has always served the aims of the bourgeoisie. But in the days when the bourgeoisie was fighting against feudalism, when it was liberating the mind, albeit its own mind, from all the burden of medieval thought, when it was setting free the productive forces, it produced writers who depicted these mighty battles.

It is enough to read Coriolanus or Richard III in order to see what titanic passion, what strain and stress the artist is portraying. It is enough to read Hamlet in order to see that the artist was confronted with the great problems of which way the world was going. The artist beat his wings against these problems. He cried: Alas that it should fall to my lot to set right a world that is out of joint. But these great problems were nevertheless the food on which he lived.

When Germany in the eighteenth century emerged from the period of her utter exhaustion, when she asked herself: “Where is the way out?” – and the way out lay in unification – she gave birth to Goethe and to Schiller.

Men the writer is able to take an affirmative attitude to reality, he can portray this reality truthfully.

Dickens painted an ugly picture of the genesis of English industrial capitalism , but Dickens was convinced that industry was a good thing, that industrial capital would raise England to a higher level, and for this reason Dickens was able to tell the approximate truth about this reality. He toned it down with his sentiment, but in David Copperfield and other works he has painted such a picture that even today the reader can see how modern England came into being.

Dickens, Balzac were able to paint harsh pictures of the contradictions of capitalism. They did so in a spirit of free creation, without fear of shaking the foundations, unashamed, for they believed in the future of the capitalist system.

There can be very talented writers. who will express in imagery the dream of the fascist cut-throats, who will describe how the blonde beast lashes the faces of the masses, and their writings will perhaps constitute great works of art.

We had such a writer in Russia – Gumilev, who gave vent to the spirit of the conquistador, of the imperialist, of the colonizer in the Russian bourgeoisie. He was an outstanding writer, and from the artistic point of view he could and did produce great things. But take this Gumilev’s books and give them, without any commentary, to our workers or our peasants. They will tell you: “He’s a scoundrel to mock at mankind like that.”

Again, there may exist outstanding fascist writers who will express the fascist dream of rule by the sword in major works of art, but these will he works which convince only the fascists themselves; they cannot become a weapon of fascist influence over the masses of the people.

We know that there are people in the Soviet Union who grumble, who are discontented. After reading works like those of Sholokhov, they come to understand, through him, what they did not understand before, when they looked at some small section of life, when they regarded only what was as yet hard for them to contemplate. Through works like Sholokhov’s they came to understand the necessity of those severe, firm, drastic measures which had to be taken in order to build socialism. I have heard with my own ears from intellectuals, from persons who were permeated with humanitarian ideas and who had not grasped what was happening during the period of the First. Five-Year Plan, during the period of collectivization when the kulak class was being liquidated, how they declared after reading Sholokhov’s book: “He has convinced me that it had to be that way.”

But show me an opponent of fascism or a neutral person whom their novels convince or will convince of the rightness of fascism, even if the novel in question, thanks to the author’s talents, attains a high artistic level.

Where will you find an artist who will be able to convince the millions of workers and peasants that a world imperialist war is a blessing? Men they were driven to the battlefields, when they were duped by the story that they were fighting for the fatherland, for themselves, they believed for a moment, but now they can see the ruins, all the consequences of war. And there is no artist who could write a true war book capable of agitating the millions in favour of imperialist war.

Try to find a major contemporary artist who will give us a truthful book about the Italian countryside – a book which would convince the peasants and us that fascism has brought liberation to the Italian countryside. Incidentally, there does exist one truthful book about Italian village life – a book by Silone, a man who has committed great political errors in his life, but who has given a truthful picture in this case, since he is an enemy of fascism. The truth about the Italian countryside can only be this: that Italian fascism has not destroyed the power of the landlord, has not done away with capitalism’s exploitation of the peasantry, has not destroyed, but has strengthened, the oppression of bureaucracy in the fascist countryside.

And if a writer possessing even such talent as Shakespeare, Michaelangelo, or Leonardo da Vinci were born today, if such a writer were confronted with the task of portraying fascist reality in a picture convincing to the masses of the people, then the picture which he produced would speak against fascism, against capitalism; he would not he able to draw one which would speak in their favour.

This is the reason why fascist literature is decaying. This is the reason why fascism will never create a great literature, a great convincing literature, convincing to the broad masses.

An art which proclaims the greatness of capitalism in the face of forty million unemployed is impossible, for, as Bernard Shaw quite rightly stated in his speech, The Madhouse in America, delivered in New York on April 11, 1933.

“Your proletariat is unemployed. That means the breakdown of your capitalist system, because, as any political scientist will tell you, the whole justification of the system of privately appropriated capital and land on which you have been working, is its guarantee, elaborately reasoned out on paper by the capitalist economists, that although one result of it must he the creation of a small but enormously rich propertied class which in also an idle class, living at the expense of the propertyless masses who are getting only a hare living, nevertheless that hare living is always secured for them. There must always be employment available; and they will always he able to obtain a subsistence wage for their labour.

“When that promise is broken (and never for one moment has it been kept right up to the hilt), when your unemployed are not only the old negligible 5 per cent of this trade, 8 per cent of that trade, 2 per cent of the other trade, but, millions of unemployed, then the capitalist system has broken down.”

What writer who is not devoid of all conscience, of all feeling, of all capacity to speak the truth can defend a system which renders tens of millions of people unemployed, a system which ruins and pauperizes the peasants, giving them no access to urban life, a system under which hundreds of thousands of people who have received an education find no chance to apply their knowledge, a system which trembles at the idea of new inventions, a system which, after the World War with its ten million killed, its tens of millions crippled and mutilated, is now preparing for a fresh war? Fascism wants to perpetuate this system; it wants to defend it from destruction by a policy of blood and iron. That is what fascism is for. Fascism can buy a handful of writers; it can find a handful of persons who will sincerely advocate the power of the blonde beast, of persons who will preach war as a panacea, but out of mercenary souls or knights-errant of historical adventure it will not be able to create a literature which will convince millions. An artist may twist as a man; as a man, he may fawn and cringe. But no one will create a great work of art by portraying what he does not believe in, by advocating a cause which he despises in the depths of his soul, for art great art, is truth and life.

There is no other art And even if there should be a handful of persons who will find romance in putrefying capitalism, – they will not be able to create works which will he convincing to the masses of the people, and they will fade away, for the creative artist needs hearts where his notes will find an echo.

The decay of capitalism, its downfall, which finds its expression in fascism, means the decay and downfall of all literature which cannot tear from its neck the fatal noose of capitalism, which cannot tear the shirt of Nessus, from its body. This does not mean that such literature cannot produce works of great craftsmanship in regard to form. The ancient world perished and rotted away, but the craftsmanship created by the artists of antiquity in the heyday of its youth lived on in the monasteries. Just as the decay of capitalism does not preclude the development of productive forces in some domain or other, in some country or other, so the decay of capitalist literature does not mean the complete disappearance of art, even in the camp of the bourgeoisie; but it does mean that no more great works will he accomplished by that art which is created in order to serve moribund capitalism. It cannot create images which will find an echo among the millions of people who aspire to a new and better life.

At best, it cannot be more than the art of minstrels who entertain revellers in a time of plague, and the artist of today who does not want to be a bard of exploitation, a bard of the burning of books, a bard of the public execution of the best sons of the people, the artist who does not want to be the bard of a new imperialist war, of a senseless and all-destroying war, must put out from that tainted coast and head for new shores, where new life is flourishing.

And those who want world literature to develop again, those who want literature of real value, those who want this great lever in the development of mankind – which has given mankind supreme enjoyment, which. fills the lives of many people, which represents a source of great creative work – to live and develop, must put off from that coast, seek their way to us, join the proletariat in the struggle against capitalism, in the struggle against fascism, for only in this struggle will a literature that is truly great arise, develop and grow strong.

https://www.marxists.org/archive/radek/1934/sovietwritercongress.htm

Hans Fallada, Kleiner Mann – was nun? pdf- estratto ita, video