Wuthering Heights (Yoshishige Yoshida, 1988)

The Criterion Collection, a continuing series of important classic and contemporary films presents Wuthering Heights.

Yoshishige Yoshida’s violent and erotic vision of Emily Brontë’s classic novel transposes its story from 19th century Yorkshire to medieval Japan to create a distinctive version of an English masterpiece. Gone are the foggy, north English moors, the titular farmhouse, and Thrushcross Grange – replaced with a steaming, volcanic mountainside and the rival East and West mansions. Onimaru (Yasaku Matsuda) is the orphan boy adopted into the Yamabe family of the East Mansion, responsible to appease the Mountain of Fire’s god. His forbidden love for Kinu (Yuko Tanaka) is frustrated when she marries into the West Mansion, inspiring Onimaru’s vengeance and madness. Yoshida’s brooding and claustrophobic Wuthering Heights celebrates the novel’s uncertainty and Gothic darkness while incorporating Shinto folklore and ritual, transgressive sexuality, and the romantic rebelliousness of the Japanese avant-garde.

Yoshishige Yoshida’s violent and erotic vision of Emily Brontë’s classic novel transposes its story from 19th century Yorkshire to medieval Japan to create a distinctive version of an English masterpiece. Gone are the foggy, north English moors, the titular farmhouse, and Thrushcross Grange – replaced with a steaming, volcanic mountainside and the rival East and West mansions. Onimaru (Yasaku Matsuda) is the orphan boy adopted into the Yamabe family of the East Mansion, responsible to appease the Mountain of Fire’s god. His forbidden love for Kinu (Yuko Tanaka) is frustrated when she marries into the West Mansion, inspiring Onimaru’s vengeance and madness. Yoshida’s brooding and claustrophobic Wuthering Heights celebrates the novel’s uncertainty and Gothic darkness while incorporating Shinto folklore and ritual, transgressive sexuality, and the romantic rebelliousness of the Japanese avant-garde.

Disc Features:

- New 2K digital film restoration, with 2.0 surround DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack on the Blu-ray edition

- Introduction by Yoshishige Yoshida

- New audio commentary by Japanese film scholar David Desser

- Making of documentary

- A new video piece by musician and scholar Philip Brophy on Wuthering Heights, Takemitsu Toru’s score, and the Japanese Gothic

- Theatrical trailer

- PLUS: A booklet of essays by Wuthering Heights scholar Hila Shachar and Japanese film scholar Isolde Standish

Inspired by Georges Bataille’s Literature and Evil and its observations on the work of Emily Brontë, Japanese intellectual and New Wave filmmaker Yoshishige Yoshida long desired to produce his vision of the classic novel Wuthering Heights. Transposing Brontë’s book to 16th century feudal Japan, Yoshida recasts the story as one of transgressive love, consummated in this case, upsetting the social order until contained and destroyed by the restoring generation that follows. Here, Lord Takamaru Yamabe returns from the capital with a brooding, willful boy, names him Onimaru for his demon-like air, and adopts him into his family. The Yamabe occupy 2 mansions on the sides of a volcanic mountain and Takamaru, head of the House of the East, protects the sacred mountain and is responsible for the annual ritual designed to appease the mountain’s god and protect the lower-lying village. Onimaru’s presence results in Takamaru’s son Hidemaru leaving the East House and Onimaru becomes its heir. Takamaru is killed by passing soldiers and his daughter Kinu avoids becoming a priestess in the capital by marrying into the rival House of the West, thereby maintaining some proximity to Onimaru despite never seeing him again. On the eve of her departure, she and Onimaru give into their desire for one another within a forbidden chamber of the East House designed to punish unruly members of the household. When Kinu leaves and Hidemaru returns with his wife and son to reclaim the House of the East, Onimaru rides off to find his fortune elsewhere.

Onimaru returns to the mountain years later a successful warrior and having been appointed by the shogun as governor of the territory, including the village, the sacred mountain, and the 2 Houses. All is not well on the sacred mountain however. Hidemaru has fallen into poverty and desperation following the rape and murder of his wife by bandits, Kinu dies from illness, and her husband, Mitsuhiko, is killed by marauders. These developments do not assist Onimaru’s already temperamental nature. Mitsuhiko’s sister, Tae, is sent to marry Onimaru but is instead treated as a servant and then raped after taunting him, causing her to hang herself from the East House’s front gate. Onimaru becomes obsessed with the deceased Kinu, twice exhuming her body from the Houses’ shared cemetary, the Valley of the Dead. Onimaru’s descent into madness and depravity is ultimately brought to a kind of end when Kinu’s daughter and Hidemaru’s son, now young adults, fatally injure him. Wuthering Heights concludes with Onimaru, improbably alive, once again possessing Kinu’s remains and dragging them farther up the sacred mountain.

Few would consider a film other than Ran (Akira Kurosawa, 1985) when naming the pinnacle of Japanese adaptations of English literature, but a strong case could be made that Wuthering Heights deserves that acclaim. In fairness, Wuthering Heights is probably not even the starting point for most interested in its maker, Yoshishige Yoshida. A prominent figure in the Japanese New Wave, Yoshida is best known for his work in the 1960s and films like Eros Plus Massacre (1969), Woman of the Lake (1966), and A Story Written on Water (1965). Wuthering Heights is a legitimate masterpiece in its own right. Yoshida’s adaptation takes the class prejudices and brooding passions of Brontë’s source novel and strains them beyond their breaking points. English propriety barely compares to the heavily ritualized world of feudal Japan, loaded with honor codes and the metaphysical religious power of Shinto. Against these constraints, Yoshida’s characters do not merely consummate their love, but delve into darker transgressions like rape, incest, and necrophilia (both metaphorical and literal). Even the shift from the Yorkshire moors to the barren and steaming slope of a volcanic mountain adds a crushingly foreboding tension with the animistic power associated with the Fire God/Serpent contained therein influencing the tragic fates of the film’s characters. Wuthering Heights is both highly claustrophobic and agoraphobic and it makes sense, given the film’s oscillation between interior and exterior spaces. In either case (claustrophobic/agoraphobic or interior/exterior), characters appear small, isolated and trapped by social and spiritual powers they are able to resist only temporarily. Full of brooding obsessions and profane acts, of romantic rebellion and madness, Wuthering Heights is late classic of Japan’s intellectual left in desperate need of a North American release and a much wider audience.

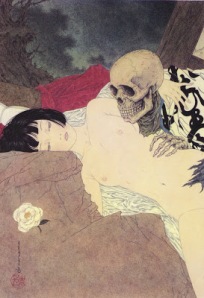

There is a fetid, mouldering quality to Yoshida’s version of Wuthering Heights. From the worm-ridden body of Kinu and the “sexual ectoplasm” that stains the walls of the forbidden chamber (to use Philip Brophy’s description) to the decaying relationships and social order at large, the film is an extended elaboration on the return of the repressed and its eventual containment. Thinking about the film’s transgressions, its dalliances with psycho-sexual body horror, and its traditional Japanese setting, it is difficult to image an artist better suited to create a cover design than Takato Yamamoto. His fascination with love, death, and metamorphosis and his expression of these themes with a calm and serene perspective perfectly suits Wuthering Heights‘ excessive formality and its black romanticism.

There is a fetid, mouldering quality to Yoshida’s version of Wuthering Heights. From the worm-ridden body of Kinu and the “sexual ectoplasm” that stains the walls of the forbidden chamber (to use Philip Brophy’s description) to the decaying relationships and social order at large, the film is an extended elaboration on the return of the repressed and its eventual containment. Thinking about the film’s transgressions, its dalliances with psycho-sexual body horror, and its traditional Japanese setting, it is difficult to image an artist better suited to create a cover design than Takato Yamamoto. His fascination with love, death, and metamorphosis and his expression of these themes with a calm and serene perspective perfectly suits Wuthering Heights‘ excessive formality and its black romanticism.

Credits: I highly recommend John Collick’s “Dismembering Devils: The Demonology of Arashi ga oka (1988) and Wuthering Heights (1939)” in Peter Reynolds’ Novel Images: Literature in Performance. In the essay, Collick reviews the Japanese history of Brontë’s novel and William Wyler’s 1939 MGM adaptation, as well as Yoshida’s resistance to Hollywood romanticism, the metaphorical reading of the Yamabe as representative of Japanese isolationism and its siege mentality, and relationship of Japanese political radicalism to the Shinto archetype of a god descending to a sacred place and possessing a human. I also strongly recommend Philip Brophy’s essay on Takemitsu Toru’s score, “Acoustic atmospherics in Yoshida Yoshishige’s Onimaru“, in Jay McRoy’s Japanese Horror Cinema and appearing on Brophy’s website as “Arashi ga oka: The Sound of the World Turned Inside Out”. There, Brophy introduces the idea of the Japanese Gothic, discusses Takemitsu’s composition (or decomposition), and examines the interplay of sonic and musical textures, of Western orchestration and Japanese signifying instrumentation, and of interior human spaces and exterior animistic landscapes. A video piece by Brophy on these ideas would be highly beneficial, taking a half-step out of the narrative to focus on some of the near subliminal aspects of Wuthering Heights that elaborate on its themes and significantly contribute the film’s effectiveness. David Desser is a regular commentary contributor for the Criterion Collection and the author of Eros Plus Massacre: An Introduction to the Japanese New Wave, making him a natural to discuss the film and its maker. The Yoshida introduction and the Making of documentary are both features from the Carlotta Films Region 2 DVD. Hila Shachar is the author of Cultural Afterlives and Screen Adaptations of Classic Literature: Wuthering Heights and Company and Isolde Standish wrote Politics, Porn and Protest: Japanese Avant-Garde Cinema in the 1960s and 1970s. Their inclusion as essay contributors would ensure a valuable feminine perspective on the film, while Shachar in particular would ensure that the relationship of Yoshida’s film to Brontë’s founding text is not missed in a Criterion edition.

https://makeminecriterion.wordpress.com/2013/05/10/wuthering-heights-yoshishige-yoshida-1988/

Wuthering Heights ; Cime Tempestose : o lo odi o lo ami …

Jane Eyre cinematic obsessions | controappuntoblog.org

Heroic Purgatory (Yoshishige Yoshida,(as Kiju Yoshida) 1970)

Funeral.parade.of.roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969 …

Fiori D’equinozio – Yasujirō Ozu – Film Completo Sub Ita

The saddest job in the world: Japan’s :” Lonely Death Squads”, qualche film giaponese

Late Spring(1949)-Yasujirō Ozu – Tarda primavera .

Era uma vez um pai / Chichi Ariki (pt, br, en, esp, fr ) Yasujiro …

Late Spring(1949)-Yasujirō Ozu – Tarda primavera …

Era uma vez um pai / Chichi Ariki (pt, br, en, esp, fr ) Yasujiro …

Il maestro burattinaio (1993) The Puppetmaster – Hsimeng .

cattivi dormono in pace , The Bad Sleep Well (1960) Akira

No Regrets for Our Youth (1946) – Non rimpiango la mia ..

Claire DENIS ei suoi films ultimo : LES SALAUDS – Macerie ..

Il cinema di Bong Joon-ho : Mother – Snowpiercer – Tokyo …

Hiroshi Teshigahara : – The Face of Another (1966) [MultiSub] – Woman in the Dunes 1964 – “Otoshiana” (“Pitfall”)

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/wp-admin/post.php?post=57595&action=edit&message=1

Cane randagio (野良犬 Nora inu) – L’idiota …

Wakamatsu Kōji – 海援ホテルブルー, Petrel Hotel Blue …

Nakagami, Kenji Mille anni di piacere – The Millennial

Tan Dun – Hero | controappuntoblog.org

Hero (China/Hong Kong 2002) : analysis e video .

Zhang Yimou’s “Red Sorghum” – Sorgo Rosso; DURA LA …

L’imperatrice Yang-Kwei-Fei : Kenji Mizoguchi – Tamasaburo

Life on a String 边走边唱 (Chen Kaige, 1991) LA VITA .

The Grandmaster – la colonna sonora del biopic con arti …

Chongqing, flash sulla megalopoli

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2013/08/29/chongqing-flash-sulla-megalopoli/

Dance Dance Dance : Murakami Haruki

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2012/10/05/dance-dance-dance-murakami-haruki/