Ustanak u Jasku

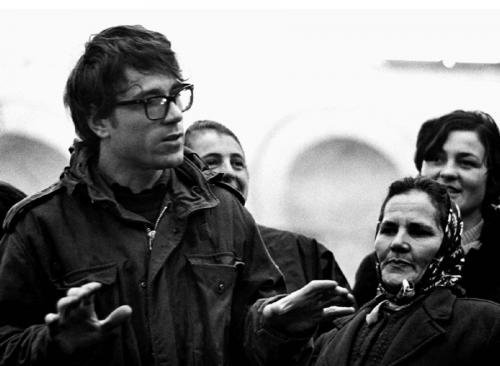

Creative Provocation: Retrospective Želimir Žilnik

Želimir Žilnik (*1942) is a resident of Novi Sad in Serbia and has been working as a director of shorts, documentaries, features, essay films, and television productions since the end of the 60s. Always radically independent, he has created an oeuvre that reflects in precise, critical terms upon the various societies and their political, cultural, and economic conditions that form the setting of his films – Socialist Yugoslavia, West Germany in the 70s, the movements toward the break-up of Yugoslavia following Tito’s death, the wars of the 90s, the transformation processes that paved the way to a market economy, and the new borders now being drawn in Europe. We are very happy to welcome Želimir Žilnik to Arsenal from January 11-13 and will be showing 20 of his films until the end of the month.

Žilnik’s first short films from the end of the 60s are an audacious blend of agitation and documentary elements that criticize the dominant system in self-reflexive fashion. Together with Dušan Makavejev, Lazar Stojanović, Karpo Godina and others, he belonged to a generation of filmmakers that challenged ossified political structures with a sense of creative provocation. The concept of the “Black Wave” thought up by cultural functionaries to defame this group was ironically taken up by Žilnik in 1971’s BLACK FILM. Žilnik won both international recognition and the Berlinale Golden Bear with his first feature RANI RADOVI in 1969, which also caused him problems back home however. He was unable to complete his next feature “Freedom or Cartoons” (1972) and was given a de facto ban on working. In 1973, Žilnik left Yugoslavia and came to West Germany like many of his countrymen. There he made 7 short documentaries, usually shot with “guest workers”, and one feature. Yet democracy too set him on a similar collision course with the authorities, his cinematic explorations of terrorism and its exploitation by the mass media (ÖFFENTLICHE HINRICHTUNG and PARADIES) leading to the police searching his house and his being swiftly deported from Germany after his tourist visa allegedly ran out. Back in Yugoslavia, television offered him new working opportunities, enabling him to shoot cheaply and simply produced films about people’s everyday lives. It was here that he developed the directorial technique of the “docu-drama”, a blend of fiction and documentary that takes real events as its starting point before receiving a certain degree of fictional padding in the form of staged scenes and dialogues. The non-professional actors play themselves, draw on their own experiences, and are granted a space to express and present themselves and their own “dramas”. This raw, minimalist aesthetic heightens the impression of the real and the unadorned. Over the last few years, Želimir Žilnik has turned his attention more and more to the political and social upheaval in the states of southeastern Europe and the people caught up in it, as well as to migrational movements and the European Union’s increasing use of deportation.

TITO PO DRUGI PUT MEDJU SRBIMA (Tito’s Second Time Among the Serbs, Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1994, 11.1., screening attended by Želimir Žilnik, & 31.1.) Despite having died in 1980, Tito turns up on the streets of Belgrade in 1994 resplendent in his best army uniform and eager to speak to his people, with animated discussions with passers-by thus ensuing. The people are suffering under hyperinflation and the war and have grown weary of both Tito’s veneration while he was still alive and his subsequent condemnation in the period that followed.

ŽURNAL O OMLADINI NA SELU, ZIMI (Yugoslavia 1967, 11. & 31.1.) Žilnik’s debut film already shows signs of his characteristic documentary fiction or arranged documentary style. He observes young people at play in Vojvodina as they hang out in bars and dance, somewhere between a sense of emptiness and an overflowing vitality for life.

CRNI FILM (Black Film, Yugoslavia 1971, 11. & 31.1.) Žilnik picks up 10 homeless people (who do not exist according to official speeches) from the streets of Novi Sad one night and takes them home with him. While they stay in the two-room flat where he lives in with his wife and little daughter, Žilnik asks passers-by on the street how the problem can be solved. “It is a film about the class structure of Yugoslavian society but also about the abuse of the déclassé for film purposes; it shows how the filmmaker exploits social hardship.” (Ž. Ž.) The final intertitle pithily expresses the dilemma: “FILM – WEAPON OR SHIT”.

USTANAK U JASZKU (Yugoslavia 1973, 11. & 31.1.) The elderly inhabitants of a village remember the war and the partisan battles. The film also relates how collective memories and myths enter into individual consciousness.

STARA ŠKOLA KAPITALIZMA (The Old School of Capitalism, Serbia 2009, 12.1., followed by a discussion with Želimir Žilnik and Boris Buden & 26.1.) The end of state socialism also entails Serbia entering the world of global capitalism. Before the real-life backdrop of a series of factory strikes, a group of workers storms the factory only to realize that the bosses have got their hands on everything already. Young anarchists then kidnap the factory owner in an act of solidarity, with the visit of a Russian grand industrialist and American vice-president Biden only serving to complicate the situation further.

NEZAPOSLENI LJUDI (Yugoslavia 1968, 12. & 23.1.) Žilnik confronts various unemployed people with a series of questions that are edited together to create a universal portrait of unemployment where no trace of socialist optimism is to be felt.

KENEDI SE VRAĆA KUĆI (Kenedi Goes Back Home, Serbia and Montenegro 2003, 13.1., screening attended by Želimir Žilnik & 28.1.) is the first part of a trilogy about young Roma Kenedi Hasani who plays the leading role himself. Having fled from the Yugoslavian wars to Germany in the 90s, he was deported to Serbia in 2002. At Belgrade airport, he meets other people thrown out of Germany who are living in transit just like him, all in search of friends and family, accommodation and orientation. Based on the experiences and accounts of the actors, the new borders being set out in the united Europe and the mechanisms for exclusion it is establishing are soon made tangible.

GDE JE BIO KENEDI 2 GODINE (Kenedi, Lost and Found, Serbia und Montenegro 2005, 13.1., screening attended by Želimir Žilnik & 28.1.) Two years after KENEDI GOES BACK HOME, Žilnik finds Kenedi Hasani again in Vienna during a screening of the very same film. He was arrested by the border police trying to illegally cross the border from Hungary to Austria and spent several months in a refugee camp. From there, he fled to Germany and Holland via Austria. He now takes a film team with him to Novi Sad where he decides to build a house for his family.

KENEDI SE ŽENI (Kenedi Is Getting Married, Serbia 2007, 18. & 29.1.) The third part of the KENEDI trilogy: After building the house in Novi Sad, Kenedi is now in debt and is looking for any work he can find. As Serbia doesn’t offer many opportunities, he decides to try his luck in the sex business. Might getting married to a EU citizen solve his problem? Just like in the other two films, Kenedi is not merely the object of the camera but is rather actively occupied with shaping the scenes from his life being reconstructed by it.

RANI RADOVI (Early Works, Yugoslavia 1969, 16. & 27.1.) Žilnik’s feature debut, named after the early works of Karl Marx (“additional dialogue: Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels”) attempts to come to terms with student hopes in Belgrade in 1968. Four young people, three men and woman, set out in a clapped-out old car to the country where they call upon the population to emancipate themselves and develop political awareness and attempt to implement revolutionary theories in practice. Frustrated by the resistance they meet and their lack of success, they turn to self-destruction. The film starts with the word “Comedy” and ends with a quotation by French revolutionary Saint Just: “Whoever only carries out half a revolution is digging his own grave!” This by turns angry and boisterous film won the Berlinale Golden Bear in 1969.

LIPANJSKA GIBANJA (Yugoslavia 1969, 16. & 27.1.) was shot during the student protests in Belgrade in spring 1968, with “Down with the Socialist Fat Cats” the slogan being shouted. Žilnik works here with interviews edited together in dynamic fashion in the style of cinéma vérité and has an actor quote Robespierre from Büchner’s “Danton’s Death”.

PIONIRI MALENI, MI SMO VOJSKA PRAVA, SVAKOG DANA NIĆEMO, KO ZELENA TRAVA (Yugoslavia 1968, 16.1.) Children and young people whom society has left to their own devices speak freely of their experiences before the camera, relating tales of life on the street, of theft, abuse and violence. One of them is little Pirika, who we meet again 45 years later in PIRIKA NA FILMU. The title is taken from a pioneer song of the time.

PIRIKA NA FILMU (Pirika on Film, Serbia 2013, 16.1.) is the portrait of a woman as well as an analysis of the post-communist status quo in the countries of the former Yugoslavia. 45 years after taking part in two films by Želimir Žilnik, RANI RADOVI and PIONIRI MALENI, the film is a hommage to the colorful life of Piroška Čapko, who is in Berlin to look for the daughter with whom she hasn’t spoken in years. Žilnik freely combines documentary elements, staged episodes (in which Arsenal also plays a role) and conversations between the different people that Pirika meets.

DUPE OD MRAMORA (Marble Ass, Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1994, 14. & 25.1.) examines the aftereffects of the wars of the 90s on people living on the margins of society. Prostitute Merlin attempts to establish peace using her own particular method, trying to counteract the atmosphere of violence by sleeping with numerous young men and thus channeling energies that would otherwise quickly turn to aggression. Johnny has just returned from the front and seeks to use yet more violence to solve his conflicts. An apocalyptic vision of a Serbian society dominated by mentally damaged people, the myth of masculinity and the war mentality. MARBLE ASS won the Teddy Award at the 2005 Berlinale.

DO JAJA (Throwing Off the Yolks of Bondage, Federal Republic of Yugoslavia 1997, 14. & 25.1.) documents the mass protests in Belgrade against the Milošević regime in Serbia in November 1997. Disillusioned by their political leaders, the demonstrators throw eggs at state institutions.

ÖFFENTLICHE HINRICHTUNG (West Germany 1974, 20. & 24.1.) is based on German television reports about police actions against the RAF, which appear to Žilnik to have been staged for TV audiences.

ICH WEISS NICHT WAS SOLL ES BEDEUTEN (West Germany 1975, 20. & 24.1.) An amusing parody of German Romanticism and how it is transformed into kitsch that draws on different versions of Heinrich Heine’s “Lorelei”.

PARADIES. EINE IMPERIALISTISCHE TRAGIKOMÖDIE (West Germany 1976, 20. & 24.1.) An unscrupulous bankrupt industrialist stages her own kidnapping in order to restore her company to profitability. She hires a group of young anarchists as kidnappers so that she can turn up again after a few days of “captivity” with renewed vigor. Directly influenced by the kidnapping of Berlin CDU Chairman Peter Lorenz by the July 2nd Movement, Žilnik creates a pastiche of the Baader Meinhof hysteria circulating at that time in West Germany. Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Hanna Schygulla were originally intended to play the leading roles, which didn’t come to fruition however. PARADIES was apparently Fassbinder’s inspiration for his own film The Third Generation.

The half-documentary TVRÐJAVA EVROPA (Fortress Europe, Slovenia 2000, 21.1.) was shot in the border regions of Italy, Slovenia, Croatia and Hungary. The southeastern border of the EU is under heavy observation in the aftermath of Schengen Treaty and is serving to strengthen the nationalist tendencies and police organs of the eastern European states. Using true stories as his starting point, Žilnik reconstructs the stories of several people trying to cross these borders: the Russian man who wants to bring his daughter to his ex-wife in Italy before getting stranded in Hungary, where he meets refugees from Serbia, or the young woman from Romania, who is apprehended by police on the Slovenian-Italian border and sent back as a result.

INVENTUR METZSTRASSE (West Germany 1975, 21.1.) shows the inhabitants of an old apartment block – primarily “guest workers” – who introduce themselves and their living situations. Playing themselves in a rigorous structuralist setting, it is they themselves who determine what and how much of themselves they reveal. (al)

With the friendly support of the Serbian Embassy Berlin. Thanks to Miloš Stipić and Želimir Žilnik

http://www.arsenal-berlin.de/en/arsenal-cinema/current-program/single/article/4566/3006.html

Figures of Dissent: Želimir Žilnik

27 November 2014 20:30, KASKcinema, Gent. A KASK lecture in collaboration with Courtisane.

27 November 2014 20:30, KASKcinema, Gent. A KASK lecture in collaboration with Courtisane.

In the presence of Želimir Žilnik

Black Film (YU, 1971, 16mm, video, b&w, 14′)

Seven Hungarian Ballads (YU, 1978, 16mm, video, colour, 30′)

Inventory (Inventur – Metzstrasse 11) (YU, 1975, 16mm, video, colour, 9′)

Tito Among the Serbs for the Second Time (YU, 1994, video, colour, 43′)

“I do not hide my camera. I do not hide the fact from people I am shooting that I am making a film. On the contrary. I help them to recognise their own situation and to express their position to it as efficiently as they can. The hidden camera is a scam. It is all right to use in films on timid animals, but it has no place in films with people. “

Among the many anecdotes for which Želimir Žilnik is well known, there is one involving a discussion he had, sometime in the beginning of the 1970’s, with Ivo Vejvoda, then one of the leading Yugoslav diplomats and communist intellectuals. Vejvoda told Žilnik that it was unfortunate that his films focused so much on the “lumpenproleteriat”, which he called “a regressive force without class consciousness”. This remark was typical for the criticism accusing Žilnik of painting a “black” picture of the Yugoslav society which was ostensibly flourishing in the wake of the political and economic reforms of the 1960’s, an accusation to which he bluntly responded by making a film which he literally titled Black Film (1971). Žilnik picked up six homeless people from the street and brought them into his home, not only to share the warmth of his middleclass apartment, but also to actively participate in making a film about their situation. Black Film stands as the quintessential example of Žilnik’s work, which tends to focus on the lives of vagabonds, swindlers, tinkers, beggars and bohemians, those who were in the Marxist tradition dismissively referred to as the ‘lumpenproletariat’, generally depicted as an inert mass of marginal and reactionary vulgars, an unredeemed and unregenerate underclass which didn’t play any structural role in the construction of socialism. This blackness then, which was so characteristic of the “black wave” cinema of the time, can be associated with the indication of this uneasy contradiction between those who were considered as true proletarians and their degenerate close cousins, all of which were allegedly unable to grasp the political reality of their own situation. It can also be related to the unveiling of the notorious gap between the utopian promise of knowledge and salvation on one hand and the reality of poverty and inequality on the other. But the blackness can just as well be implicated on cinema itself, this art form which used to claim to have the power to change social reality, but in the end has to agree that it can offer nothing but a surface of percepts and affects for us to engage with. “They left us our freedom”, Žilnik wrote in a text accompanying a screening of the film, “we were liberated, but ineffective”. In spite of this self-reflexive critique, Žilnik stubbornly persevered in making films, even up to this day. The political landscape might have changed, but not the filmmaker’s attitude, which remains loyal to the uncovering of the difficult legacy of socialism and the predicaments of those who were once called lumpen, who are today said to be included but hardly belonging.

On 26 November, Želimir Žilnik will also present some of his work at Cinema Nova, Brussels.

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

http://www.diagonalthoughts.com/?p=2139

Rani radovi / Early Works _ Želimir Žilnik

Stara škola kapitalizma

[Video clip] Seven Hungarian Ballads | Želimir Žilnik

Early life

Želimir was born in the Nazi-run Crveni Krst concentration camp in September 1942 where his Serbian communist activist mother Milica “Maša” Šuvaković was imprisoned by Germans since early 1942. On 2 December 1942 there was a prison break in the camp as a group of prisoners managed to escape, and as a response – the Germans executed a number of remaining prisoners including Maša Šuvaković. Days before his mother was executed, 3-month-old Želimir was taken out of the prison and given to her parents. Young Želimir was thus raised by his maternal grandparents.

His father was a Slovene communist activist and Partisan fighter Konrad “Slobodan” Žilnik who got severely wounded and taken prisoner in March 1944 during a battle against Chetniks. Chetniks tortured him and eventually executed him couple of days later. Posthumously, he was awarded the People’s Hero gallantry medal.

Career

He won his first awards, a Golden Berlin Bear and a Youth Film Award at the 19th Berlin International Film Festival in 1969 for his feature film Rani radovi[1] (Early Works) which depicted the aftermath of the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia.

During the early 1970s he was criticized and his works were quite often banned due their[2] portrayal of student demonstrations and their advocacy of freedom of media and speech. Between 1973 and 1976 he found work for several independent German production companies. In conjunction with these companies he directed two documentaries dealing with anarcho–terrorism; Öffentliche Hinrichtung[3] and Paradies.[4] In Yugoslavia he found work in theatre production but returned to his previous work with documentaries.

In the 1980s his works began to garner more attention and were successfully presented on several television networks and at local and international festivals. In 1985 he made Pretty Women Walking Through the City which predicted that nationalistic tensions will cause the disintegration of Yugoslavia. His 1988 his black comedy Tako se kalio čelik[5] (The Way Steel Was Tempered) was nominated for the Golden St. George award at the 16th Moscow International Film Festival in the Soviet Union.[6]

In 1994 he wrote and directed Tito’s Second Time Among the Serbs, and helped initiate one of Serbia‘s independent media outlets, b92 in Belgrade. His 1995 feature film Marble Ass was a look at the myth built around the masculinity of the male as a warrior and leader. It was entered into the 19th Moscow International Film Festival.[7]

Recently he has directed several documentaries dealing with the commonality of the Central and Eastern Europe and the problems with immigration to and from Europe[8] with the same style and narrative that had gained him recognition for many years.

Selected filmography

- Jedna žena, jedan vek (2011)

- Stara škola kapitalizma (The Old School of Capitalism) (2009)

- Kenedi se ženi (Kenedi is Getting Married) (2007)

- Gde je bio Kenedi 2 godine (Kenedi, Lost and Found) (2005)

- Kenedi se vraca kuci (Kenedi Goes Back Home) (2003)

- Tvrdjava Evropa (Fortress Europe) (2001)

- Kud plovi ovaj brod (Wanderlust) (1999)

- Marble Ass (Marble Ass) (1995)

- Tito po drugi put medju Srbima (Tito Among the Serbs for the Second Time) (1993)

- Tako se kalio čelik (The way Steel was Tempered) (1988)

- Abschied (Farewell) (1976)

- Paradies (Paradise) (1976)

- Rani radovi (Early Works) (1969)