La fiammiferaia (Aki Kaurismäki, 1989)

Terzo film della cosiddetta “trilogia dei perdenti” (Ombre in paradiso del 1986 e Ariel del 1988 gli altri due) è anche il più intriso di pessimismo. Anzi, forse il pessimismo è il vero soggetto del film, e per questo certe sequenze ricordano e quasi portano lo sguardo nel melodramma. Ma Kaurismäki non cede al grande respiro del genere, non si lascia trascinare dagli sviluppi di una storia che avrebbe potuto dilatare all’inverosimile il dramma, fino a raggiungere l’espressione del più grande dolore dell’io “torturato” da un mondo crudele. Eppure i contenuti ci sono tutti: donna sola che mantiene, col suo lavoro in una fabbrica di fiammiferi, madre e patrigno, i quali la disprezzano e la ripudiano alla prima occasione; Arne, amante egoista e crudele che la usa per una notte, per poi abbandonarla (dopo aver conosciuto la sua famiglia e averla condotta in un locale, le dice: “Se però pensi che tra noi ci possa essere un rapporto, ti sei sbagliata di grosso. Niente potrebbe interessarmi meno del tuo affetto. E adesso credo che puoi anche sparire”); un bambino, frutto della sua unica notte con Arne, che sta per nascere; la vendetta e il conseguente epilogo. Ingredienti tipici del melodramma che Kaurismäki non lascia decollare. Al contrario, l’aspetto più drammatico e angosciante del film non è il racconto preso di per sé, ma il modo di porsi di immagini e riprese nel costruire una storia tanto sconvolgente quanto impossibile. Innanzitutto Kaurismäki interviene con il suo metodo più caratteristico, ossia una sceneggiatura minimalista passata attraverso una riduzione estrema dei dialoghi (la prima frase viene pronunciata da Iris dopo circa tredici minuti “Mezza birra”; altri sei minuti circa prima che il patrigno, schiaffeggiandola le dica “Puttana!”). Mentre le ellissi delegano allo spettatore il compito di ricostruire i momenti più drammatici o pregnanti (l’incidente di Iris o la notte d’amore tra Iris e Arne) la macchina da presa indugia sugli oggetti, sui comportamenti e le abitudini quotidiane dei pochi personaggi. L’incipit ad esempio mostra minuziosamente la catena di montaggio della fabbrica di fiammiferi attraverso la lavorazione di un tronco fino alla sua trasformazione in prodotto finito. In particolare questa lunga sequenza iniziale (oltre tre minuti), composta da inquadrature di macchinari che lavorano il legno fino a trasformarlo in fiammiferi inscatolati, è come un’istanza estrattiva di un “reale” amorfo, reso “emblema” di uno status quo che non può essere alterato. Questa istanza “astratta” non è contenuto verosimile e/o rappresentazione ma, come direbbe Barthes, una collusione tra referente e significante. Dettagli superflui (bastava una voce off per metterci al corrente sulla professione di Iris), riempitivi che permettono l’espulsione del significato dal segno. Ciò può causare un senso di irrealtà, di inverosimiglianza. Per questo motivo Barthes contrappone il nuovo verosimile (l’effetto di reale) al vecchio verosimile, all’opinabile (l’assoggettato all’opinione del pubblico). Per Barthes l’effetto di reale non sono altro che i dettagli inutili, superflui, che fanno parte della narrazione, di certe situazioni descrittive, apparentemente funzionali alla «storia». In realtà questi dettagli non hanno alcuna funzione significante. Questi riempitivi, queste “catalisi”, effetti di reale, definiscono il sapore della vita quotidiana, restituiscono allo sguardo quegli oggetti, quei gesti ormai automatizzati, ossia , come afferma Šklovskij , “[…] considerati nel loro numero e volume […]” (2), senza essere visti, ma conosciuti “[…] soltanto per i loro primi tratti “. (2). Inoltre Kaurismäki “indebolisce” i cosiddetti “nuclei narrativi” (le sequenze significanti), non solo relegandoli all’interno dell’ellisse e quindi lasciandoli macerare nel regno dell’opinabile, ma anche eclissandoli dentro la stessa visione, abbandonandoli nell’attimo in cui sono prodotti. Quando Iris viene investita da un’auto, sappiamo dell’evento che accade nel fuori campo solo attraverso il rumore acusmatico di una frenata. Per un attimo, nel “mentre” della dissolvenza in nero, non siamo a conoscenza della gravità dell’incidente: Iris potrebbe essere gravemente ferita o addirittura morta, potrebbe aver riportato conseguenze permanenti. Solo la scena seguente ci informa che Iris non è grave, la vediamo nel letto d’ospedale lucida e consapevole. Ma la maestria di Kaurismäki consiste proprio nell’insistere sull’indebolimento dei nuclei narrativi: adesso l’incidente non conta più, infatti la sequenza inizia col patrigno di Iris che sale le scale dell’Ospedale, entra nella stanza comunicando alla figliastra che sua madre non la vuole più vedere. In questa scena si vede solo il busto del patrigno, testa e braccia sono tagliate fuori dal quadro: non interessa mostrare l’espressione dura o ipocritamente compassionevole di un uomo che non è mai stato capace di amare la sua figliastra, interessa solo allontanare “il reale” dal mondo di Iris, mostrare l’isolamento interiore della donna, riducendo e sezionando l’esterno. Le parti anatomiche degli altri personaggi sono trattate e mostrate meno degli oggetti. Durante la sequenza del ballo, quando Iris è seduta accanto ad altre ragazze in attesa di essere invitata, vediamo solo alcune “parti” di figure maschili che si presentano alle donne per invitarle a ballare. Iris, sempre inquadrata, rimane sola sulla panca: questa semplice immagine trasferisce nel fuori l’angoscia e la sofferenza del dentro, coinvolgendo lo sguardo e trascinandolo in un abisso. Tutto questo reso attraverso catalisi, riempitivi, ossia oggetti, pezzi di figure, fuori campo, silenzio. Al contrario forse gli oggetti acquistano una sorta di superiorità sui personaggi. In fondo il film ha un solo vero, unico personaggio. Lo spazio si chiude sempre su di lei, lasciando ai margini e quasi abbandonando gli altri in un magma evanescente quasi de-realizzato. Gli oggetti della vita quotidiana invece sono mostrati con minuziosa attenzione, seguiti nel loro rapporto con le abitudini

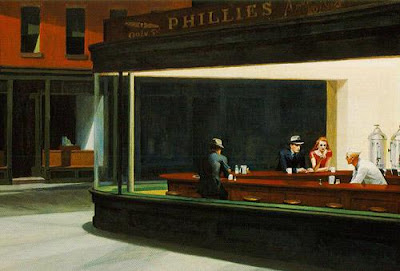

e i gesti della giovane donna. Il vestito nuovo, acquistato per essere indossato dalla donna allo scopo di essere più attraente e permetterle di essere portata sulla pista, diventa l’oggetto fondamentale del film, causa e conseguenza di tutti gli eventi che capiteranno. Il vestito rende Iris più attraente e invoglia Arne ad invitarla a ballare; per pagare il vestito Iris ha dovuto prendere i soldi dalla busta paga e siccome lo stipendio viene consegnato alla madre, l’acquisto non passerà inosservato. Anche la boccetta contenente il veleno per topi acquista una sua valenza ogni volta che viene usata da Iris. La sua vendetta personale non viene mostrata in maniera melodrammatica, ma simbolica, attraverso l’uso banale del veleno contenuto in una boccetta. Ogni volta che Iris travasa il liquido in un bicchiere di scotch o in una bottiglia d’acqua, sappiamo già cosa accadrà, lo sappiamo, lo intuiamo, ma Kaurismäki non ci mostrerà mai le conseguenze di quel semplice travaso si si esclude la sequenza dei due agenti in borghese che arrivano sul luogo di lavoro per prelevare Iris. Nel suo minimalismo spinto ai limiti della totale dissolvenza del film ( è possibile andare oltre, fino ad entrare nell’astrazione totale pur rilasciando “messaggi” realistici?) Kaurismäki concede largo spazio alla musica e alla tv, alle canzoni cantate nella sala come a quelle che fuoriescono da radioline o alla musica extradiegetica, e ai telegiornali ascoltati dalla madre e dal patrigno di Iris, da due mummie impassibili e irrecuperabili, due “oggetti” assenti e surreali. In particolare Kaurismäki intende mostrare il mondo attraverso la tv, confrontare un dramma sociale e “distante” (i fatti memorabili e spaventosi della Piazza Tien An Men a Pechino) con il dramma personale che contiene, come nella piazza cinese, già i germi della sua sconfitta. Questa particolare attenzione agli oggetti, questa “[…] capacità leggera di trasferire nel contesto cinematografico le idee migliori della pittura […]” si esplica nel juke-box e nel biliardo dell’appartamento del fratello di Iris. Dalla “[…] contraddizione tra questi oggetti e dalla stilizzazione a cui vengono sottoposti [..] nasce la tensione fantastica del film. Sono immagini in cui Kaurismäki si dimostra più che mai vicino all’universo di Edward Hopper”. (3)

http://cinemante.blogspot.it/2008/07/la-fiammiferaia-aki-kaurismki-1989.html

Un Kaurismäki pessimiste

Kaurismäki, dans toute sa splendeur, pousse ici ses choix artistiques à leurs extrêmes. Une chronique ouvrière déprimante et pourtant teinté de couleur qui se transforme finalement en marathon vengeur (un peu à la manière de la pièce Liberté à Brême de Fassbinder, mais en moins élaboré). Kaurismäki filme cette chronique telle qu’elle pourrait se présenter dans la réalité, il filme un morceau de vie quelconque dans lequel entrent les personnages, puis en ressortent, et cela pour la plupart des plans, ce qui rend le travail de montage très intéressant et très efficace. Son économie des dialogues, si propre à son style, sert parfaitement le propos du film. Iris évolue dans un univers vide, fait de répétitions et de monotonie à l’image de ces machines qu’elle côtoie dans son usine, rêve et tente de s’en extirper mais ne rencontre que des embûches. Mais cette fois-ci, et c’est peu commun chez le cinéaste, le film reste relativement pessimiste quant à l’issue de cette quête désespérée.

Kaurismäki, dans toute sa splendeur, pousse ici ses choix artistiques à leurs extrêmes. Une chronique ouvrière déprimante et pourtant teinté de couleur qui se transforme finalement en marathon vengeur (un peu à la manière de la pièce Liberté à Brême de Fassbinder, mais en moins élaboré). Kaurismäki filme cette chronique telle qu’elle pourrait se présenter dans la réalité, il filme un morceau de vie quelconque dans lequel entrent les personnages, puis en ressortent, et cela pour la plupart des plans, ce qui rend le travail de montage très intéressant et très efficace. Son économie des dialogues, si propre à son style, sert parfaitement le propos du film. Iris évolue dans un univers vide, fait de répétitions et de monotonie à l’image de ces machines qu’elle côtoie dans son usine, rêve et tente de s’en extirper mais ne rencontre que des embûches. Mais cette fois-ci, et c’est peu commun chez le cinéaste, le film reste relativement pessimiste quant à l’issue de cette quête désespérée.

http://www.senscritique.com/film/La_Fille_aux_allumettes/434557

The Match Factory Girl

This poor girl. I wanted to reach out my arms and hug her. That was during the first half of “The Match Factory Girl.” Then my sympathy began to wane. By the end of the film, I think it’s safe to say Iris gives as good as she gets.

This poor girl. I wanted to reach out my arms and hug her. That was during the first half of “The Match Factory Girl.” Then my sympathy began to wane. By the end of the film, I think it’s safe to say Iris gives as good as she gets.

The film begins with a big log. In documentary style, we see what happens to it. It has its bark stripped off. Blades shave thin sheets from it. These sheets are chopped into matchsticks and divided and stacked and dipped and arrayed and portioned into boxes, which are labeled, packed into larger boxes, and labeled again. That’s where Iris comes in. At first we see only her hands, straightening labels, sticking them down, removing duplicates. Then we see her face, which reflects absolutely no emotion.

The Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki fascinates me. I am never sure if he intends us to laugh or cry with his characters–both, I suppose. He often portrays unremarkable lives of unrelenting grimness, sadness, desolation. When his characters are not tragic, he elevates them to such levels as stupidity, cluelessness, self-delusion or mental illness. Iris, the match factory girl, incorporates all of these attributes.

She is played by the actress Kati Outinen, a Kaurismäki favorite who has often starred for him. Whatever it is she does, she is very good at it. His camera stares at her, and she stares back. She is a pale blonde, slender, with a receding chin and eyes set deep in pools of mascara. If she were to laugh, that would be as novel as when Garbo talked for the first time. It would be easy to describe her as “plain,” but you know, she would have a pretty face if she ever animated it with a personality. In “The Match Factory Girl” she is deadpan and passive, a person who is accustomed to misery.

Her job at the match factory is boring and thankless. She is one of the few humans among the machines. She takes the tram home to Factory Lane, where a shabby alley door admits her to the two-room apartment she shares with her mother and stepfather. They sit in a stupor watching the news on TV. Her mother smokes mechanically, so listless long ashes gather on her cigarette. Iris cooks dinner, serves it, and sits down with them. A soup has pieces of meat in it, and her mother reaches out a fork and stabs a bite from Iris’ plate. She is expected to do all the cleaning, sleep on the sofa, and pay rent.

In the evenings she goes out seeking companionship, and is ignored. At a club, nobody asks her to dance. In a bar, she locks eyes with a bearded man. His gaze is aggressive, not affectionate. They sleep with one another. He never calls her again. She goes to his flat to indicate she cares for him. He tells her, “Nothing could touch me less than your affection.” That’s all he ever says to her. Her stepfather says less. “Whore,” he calls her, after she spends some of her paycheck on a pretty red frock.

I watched hypnotically. Few films are ever this unremittingly unyielding. I found myself as tightly gripped as with a good thriller. I could hardly believe the litany of horrors. What made it more mesmerizing is that it’s all on the same tonal level: Iris passively endures a series of humiliations, cruelties and dismissals. This cannot be tragedy because she lacks the stature to be a heroine. It cannot be comedy because she doesn’t get the joke. What can it be?

Kaurismäki has made many films with hapless characters. When I say that when I see each one it makes me eager for the next. I suppose my description makes this one sound depressing, but although it is about a depressed woman it is always challenging us, nudging, teasing our incredulity. When Kaurismäki has an entry in a film festival, I will make it my business to see it.

I’ve reviewed four of his other films: “Ariel” (“the character’s lack of physical and social finesse is a positive quality”) ; “Lights in the Dusk” (“his characters are dour, speak little, expect the worst, smoke too much, are ill-treated by life, are passive in the face of tragedy.”) ; “Drifting Clouds” (“he wants his characters to always seem a little too large for their rooms and furniture”) ; and “The Man Without a Past” (“He finds a community of people who live in shipping containers. There is a kind of landlord, who agrees to rent him one”).

Not all of these films are as dour as “The Match Factory Girl.” Some of his characters are more resilient. I never get the idea he hates them; in fact, I think he loves them, and feels they deserve to be seen in his movies, because they are invisible to other directors. In making them, he seems to be consciously resisting all the patterns and expectations we have learned from other movies. He makes no conventional attempt to “entertain.” That’s why he’s so entertaining. He wants only to hold our interest. He wants us to decide why he chooses such misfits, loners and outsiders, and to ask how they endure their lives. Even those who are not victims have a passive acceptance bordering on masochism. Life has dealt them a losing hand, and that’s how it is.

Kaurismäki’s camera work is meticulous. He composes without any eagerness to put elements in or leave elements out; his camera simply votes “present,” and gazes with the same dispassionate eyes that Iris has. An image is there before us. We see it. There you have it. We can draw our own conclusions. He doesn’t go in for reaction shots, or perhaps it would be more fair to say that every shot is a reaction shot. Asked at a film festival why he moves his camera so little, he explained: “That’s a nuisance when you have a hangover.”

He is often compared to Robert Bresson, who also made films about isolated, lonely characters (“Mouchette,” about a village outcast; “Diary of a Country Priest” about a disliked and unsuccessful young priest; “Au Hasard Balthazar” about a mistreated donkey). Both directors use an objective gaze. Both move deliberately. (Told he must have been influenced by Bresson, Kaurismäki said, “I want to make him seem like a director of epic action pictures.”) Actually few directors are more different. Bresson’s films are deeply empathetic, spiritual, transcendental. Kaurismäki seems detached from his characters. Most of his films could open with the title card, “Here’s another sad sack.”

But there’s something concealed beneath the attitude of detachment. He invites us to peer closely at these people he pins so precisely to the screen. What does it say that there can be such lives? How do people endure it? How do some of his characters even prevail? In “Drifting Clouds” again starring Kati Outinen as a luckless waitress with a jinxed husband, there is actually dark humor in the way the clouds are always dark and rainy. As sad as her life is, the film is immensely amusing in its over the top bad luck. When her luck changes at the end, it’s thanks to the Helsinki Workers’ Wrestlers Association.

Growing up in Finland Kaurismäki would certainly have heard Hans Christian Andersen’s story “The Little Match Girl.” It told the story of a waif in the cold on Christmas Eve, trying to sell matches so her father will not punish her. To keep warm she lights one match after another, and they summon visions which give her comfort. She finally finds happiness of a heartbreaking sort.

In the early scenes of this film Iris doesn’t smoke at all. When she finally lights a cigarette–with a match from her factory–it summons visions for her; ideas of revenge. We watch as she acts on these notions. Does she find happiness? That would be asking too much. But she finds… satisfaction.

“The Match Factory Girl” is the third film in Kaurismaki’s Proletariat Trilogy. It follows “Shadows in Paradise,” about a aimless garbage collector and “Ariel” (1988), about a coal miner who escapes his subterranean work by turning to crime. The three films have been packaged together and released by Criterion.

http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-the-match-factory-girl-1990