Elia Kazan, figlio di un venditore di tappeti greco emigrato in America, è il regista che chiese a un certo Brando di fare a pugni a sangue al porto di New York e poi salire in soffitta a occuparsi degli uccellini dell’adolescente Eva Marie Saint. Era il 1947. Su Fronte del porto piovverò sette Oscar e un Leone d’oro. Inventando, con lo sceneggiatore Budd Schuiberg, un selvaggio gentile e coraggioso destinato alla sconfitta degli eroi maledetti, Kazan lanciò Marion Brando al cinema, il giovanotto scontroso e irrequieto a cui aveva affidato la parte dello stupratore in cannottiera nella versione teatrale di Un tram che si chiama desiderio, diretto al cinema quattro anni dopo. Cineasta di denuncia sociale dei cinema americano dei dopoguerra, straordinario ottimizzatore dei genere noir in chiave di critica sociale, tra Dassin e Dmytryck: ma così, oggi, la sua opera finisce per sembrare un po’ morta. E invece, nella esperienza di Kazan c’è un pezzo di storia dell’arte cinematografica americana. Storia dell’arte perché nell’idea un artigianato (invenzione, cura, ricerca e fabbricazione) è incominciata l’avventura di Kazan nello spettacolo ed è continuata sui grandi palcoscenici di Broadway come nell’industria hollywoodiana, con successi internazionali di critica e di pubblico a volte impressionante. Della ventina dì film diretti in trent’anni, tra il 1945 e il 1976, dall’esordio con Un albero cresce a Brooklyn (un melò familìare) a Gli ultimi fuochi (ispirato al tycoon Irvin Thalberg, dal romanzo incompiuto di Fitzgerald), sette hanno conquistato, nelle diverse categorie, 20 premi Oscar. Kazan ne ha vinti tre, due per la regia di Barriera invisibile e Fronte dei porto e uno alla carriera, nel 1999.

Elia Kazan, figlio di un venditore di tappeti greco emigrato in America, è il regista che chiese a un certo Brando di fare a pugni a sangue al porto di New York e poi salire in soffitta a occuparsi degli uccellini dell’adolescente Eva Marie Saint. Era il 1947. Su Fronte del porto piovverò sette Oscar e un Leone d’oro. Inventando, con lo sceneggiatore Budd Schuiberg, un selvaggio gentile e coraggioso destinato alla sconfitta degli eroi maledetti, Kazan lanciò Marion Brando al cinema, il giovanotto scontroso e irrequieto a cui aveva affidato la parte dello stupratore in cannottiera nella versione teatrale di Un tram che si chiama desiderio, diretto al cinema quattro anni dopo. Cineasta di denuncia sociale dei cinema americano dei dopoguerra, straordinario ottimizzatore dei genere noir in chiave di critica sociale, tra Dassin e Dmytryck: ma così, oggi, la sua opera finisce per sembrare un po’ morta. E invece, nella esperienza di Kazan c’è un pezzo di storia dell’arte cinematografica americana. Storia dell’arte perché nell’idea un artigianato (invenzione, cura, ricerca e fabbricazione) è incominciata l’avventura di Kazan nello spettacolo ed è continuata sui grandi palcoscenici di Broadway come nell’industria hollywoodiana, con successi internazionali di critica e di pubblico a volte impressionante. Della ventina dì film diretti in trent’anni, tra il 1945 e il 1976, dall’esordio con Un albero cresce a Brooklyn (un melò familìare) a Gli ultimi fuochi (ispirato al tycoon Irvin Thalberg, dal romanzo incompiuto di Fitzgerald), sette hanno conquistato, nelle diverse categorie, 20 premi Oscar. Kazan ne ha vinti tre, due per la regia di Barriera invisibile e Fronte dei porto e uno alla carriera, nel 1999.

Per non rischiare di sottovalutare l’impatto di Kazan sulla formazione di alcuni modelli culturali dei cinema americani, si deve sfogliare la sua filmografia pensando agli attori che ha lanciato, sfruttando nel cinema l’enorme lavoro pedagogico dei laboratorio (l’Actors Studio) fondato con John Strasberg a metà degli anni Trenta (quando incominciarono a spostare sul piano psicologico e psicanalitico il lavoro sul personaggio dei russo Stanilslavskij). Nel 1955 Kazan affida all’esordiente James Dean la parte di Cal, il giovane ribelle di La valle dell’Eden, straordinaria zattera dei dannati della famiglia americana in cinema-scope. Nel 1956 esplode la venticinquenne Carrol Baker in uno dei film più erotici dei cinema americano, Baby Doll. Nei 1961 lancia l’esordiente Warren Beatty in una delle più strazianti storie d’amore giovanile, Splendore nell’erba (Sophia Loren soffiò l’Oscar a Nathalie Wood con La ciociara). Nel 1947 Kazan aveva dato la possibilità di un ruolo socialmente impegnato, come giornalista che sfida l’antisemitismo al giovane Gregory Peck, in Barriera invisibile. Nel ‘1957 la scoperta di Lee Remick uscì dal successo di Un uomo nella folla, grottesco film di denuncia della deformata industria culturale americana. Se balziamo al 1976, a Kazan il giovanissimo De Niro deve la parte di protagonista di Gli ultimi fuochi. Tra i grandi film (e non vanno trascurati Pinky la negra bianca, Fango sulle stelle o il riuscito L’uomo dell’Anatolia) Brando deve a Kazan Viva Zapata! (‘1952) e il già citato Un tram che si chiama desiderio, dei quale Morandini scrisse negli anni 50: “Kazan si affida alla violenza della parola per suggerire le pulsioni di morte che dominano il testo”.

http://www.mymovies.it/critica/persone/critica.asp?id=36855&r=571

«Che genere di persona deve imparare a essere un regista? Un cacciatore bianco, che guida un safari in territori pericolosi e sconosciuti. Uno psicanalista, che tiene in piedi un paziente, malgrado intollerabili tensioni. Un ipnotizzatore, che lavora con l’inconscio per raggiungere i propri scopi. Deve avere la scaltrezza del commerciante di un bazar di Bagdad. La fermezza di un addestratore di animali. La dolcezza di una madre che tutto perdona. La severità di suo marito che non perdona niente. L’abilità di un ladro di gioielli, le chiacchiere suadenti di un pierre. Una pelle dura, un’anima sensibile. Contemporaneamente.» (Elia Kazan, “On what makes a director”)

E’ stato definito il più grande director di attori che abbia attraversato il cinema americano: sapeva riversare nei suoi film, talvolta esasperandole con punte di vero sadismo, le ostilità del set tra attori, trasformandole in memorabili momenti di tensione drammatica tra personaggi.

E’ stato definito il più grande director di attori che abbia attraversato il cinema americano: sapeva riversare nei suoi film, talvolta esasperandole con punte di vero sadismo, le ostilità del set tra attori, trasformandole in memorabili momenti di tensione drammatica tra personaggi.

Sua è la paternità cinematografica di due icone assolute del ventesimo secolo di celluloide come Marlon Brando e James Dean. Ha collaborato con alcune delle figure più influenti della letteratura mondiale del dopoguerra: Tennessee Williams, John Steinbeck e Harold Pinter. E’ l’oggetto di devota adorazione di Martin Scorsese, che gli ha dedicato il vibrante A Letter to Elia.

Kazan incarna una presenza ineludibile nella storia del cinema. Il suo percorso creativo, iniziato nel Group Theatre, la “comune” di attori che avrebbe rivoluzionato la drammaturgia americana dalle fondamenta, e poi traslato sul grande schermo, ha prodotto pellicole straordinarie, di assoluto valore. A Letter to Elia, presentato nel corso dell’ultima Mostra del Cinema di Venezia e da qualche giorno disponibile in DVD grazie ad una ottima edizione curata dalla Cineteca di Bologna corredata da un prezioso volume di “Appunti di regia”, è una commossa dichiarazione d’amore del regista newyorkese nei confronti del cinema di Kazan, influenza giovanile determinante nel condurre Scorsese oltre lo schermo, dietro la macchina da presa, sulle tracce di una idealizzata figura paterna che gli parlava attraverso i suoi film.

Dirompente, vigoroso, arrabbiato: il linguaggio cinematografico di Kazan rifugge tutte le pacificazioni, collocando la tensione interna ai rapporti umani dentro contesti di apparente appagamento esistenziale, tutto americano. Prima di molti altri Kazan ha svelato il prezzo, elevatissimo, in termini di perdita e rinuncia insito nel miraggio inseguito, e nonostante tutto vitale, di una società libera e giusta.

America, America (il suo film preferito) ne è il manifesto, ed il fulcro attorno a cui ruota tutta la sua filmografia: un ampio affresco, cadenzato su toni solenni ed epici, del grande viaggio “di liberazione” e di formazione di un giovane greco dell’Anatolia verso gli Stati Uniti. Un viaggio che si conclude con il distacco, emblematico, dal vecchio nome a favore di uno nuovo, costruito sulla deformazione fonetica del vecchio. America, America prima e dopo tutti gli altri film, partenza e approdo, nòstos “a rebour” alla ricerca di perdute identità di individuo e di popolo, atroce apologo di una reconquista che passa attraverso la spoliazione: l’acquisizione di uno statuto di libertà previa rinuncia al possesso del nome.

I primissimi film alla Fox sono per ammissione dello stesso Kazan teatro filmato. La vera grande svolta arriva nel 1947, con un Oscar per il miglior film e uno per la migliore regia: con Barriera invisibile (Gentleman’s Agreement, 1947) Kazan scandaglia i labili confini che separano ipocrisia perbenista e antisemitismo nella New York appena uscita dal secondo conflitto mondiale. Il risultato è troppo blando per soddisfare Kazan, ma perfetto per garantirgli successo di pubblico e buone recensioni: per i veri capolavori ci sarà tempo.

In Bandiera gialla (Panic in the streets, 1950), sullo sfondo di una notturna New Orleans portuale, umida e allucinata, racconta la serrata vicenda di una caccia all’uomo, immagine evocativa di un’altra caccia che Kazan comincia a vivere sulla sua pelle: un immigrato, portatore di un germe contagioso, da braccare, isolare ed eliminare. Non prima di averlo costretto a fare i nomi dei suoi complici. In Viva Zapata! (1952) tratteggia un profilo chiaroscurale di Emiliano Zapata e della sua rivolta mutilata contro il potere, cucendolo sul volto e sulle spalle di Brando.

Nel 1956 con Baby Doll vira verso uno stralunato detour dentro il Grottesco del Sud, affondando un eccellente terzetto di interpreti (Karl Malden-Carrol Baker-Eli Wallach) nella limacciosa reppresentazione (da Tenessee Williams) di un evaporato e decadente menage a trois non consumato e con minorenne, attirandosi la scomunica per oscenità dal pulpito del cardinale Spellman. Un volto nella folla (A face in the crowd, 1957), profetico come pochi altri film, guado scomodissimo tra quarti e quinti poteri, diagnostica con lucidità clinica l’aberrazione della politica in formato televendita e mette in guardia dai nuovi totalitarismi striscianti dietro i mezzi di comunicazione di massa.

Con lo splendido Fango sulle stelle (Wild River, 1960) dipinge il volto più crudele e contraddittorio dell’America profonda: la Tenessee Valley Authority, le piene del Cherokee River e l’incapacità di conciliare il progresso con il fluire inarrestabile dell’acqua, del sangue, del tempo. In Splendore nell’erba (Splendor in the grass, 1961) fa deflagrare sul grande schermo il dramma di una educazione sentimentale repressiva e autoritaria, che produce scarti di consapevolezze perdute tra i versi di Walt Whitman e tardive ammissioni di colpa.

Il compromesso (The Arrangement, 1969), forse il più “disperso” dei suoi film, delinea ancora linee di sangue e occasioni mancate, abbozzando il tentativo di una sintesi di tutto il suo cinema precedente. Il suo ultimo film, Gli Ultimi Fuochi (The Last Tycoon, 1976) è il commiato crepuscolare e, nuovamente, irrisolto da un intero mondo: lo strapotere degli Studios, i grandi produttori alla Irving Thalberg, gli scioperi degli sceneggiatori, i registi-manovali al soldo delle grandi produzioni. Una scenografia di cartapesta abitata dal fantasma di John Carradine e dalle ombre di un passato che sembra, ormai, lontanissimo e perduto per sempre.

I suoi tre film più celebri, Un tram che si chiama desiderio (A Streetcar named desire, 1951), Fronte del porto (On The Waterfront, 1954) e La valle dell’Eden (East of Eden, 1955), hanno esplorato le dinamiche del conflitto (generazionale, sessuale e sociale) con estrema acutezza di sguardo, e con intensità ineguagliata. Nel cinema di Kazan lo stridente innesto di pulsioni esplosive nel decoro (formale e morale) di un rigoroso schema di rappresentazione genera sempre una frizione decisiva: tra un contesto statico, gelido, ingessato e l’azione di alcuni straordinari rebels with a good cause, impulsivi, violenti, mossi da passioni febbrili e istinti impetuosi.

La deviazione innescata, sabotaggio impercettibile ma significativo della norma, si protende verso il punto di fuga inafferrabile di un corridoio buio, si trasferisce nell’improvviso scatto di un movimento di macchina, o si manifesta nella necessità di una inquadratura obliqua. A significare l’adozione di un punto di vista che non può non dichiararsi, al culmine di ogni contrasto, alterato, dismorfico, deformato. Sradicato e piantato in un altrove di vecchie promesse e di nuove minacce. Quello di un uomo che definiva se stesso «a Greek by blood, a Turk by birth, and an American because my uncle made a journey».

http://www.paperstreet.it/cs/leggi/1074-A_Letter_to_Elia_.html

On the Waterfront

On the Waterfront

(United States, 1954, 108 minutes, b&w, 35mm)

Directed by Elia Kazan

Based on a screenplay by Budd Schulberg

Starring:

Marlon Brando . . . . . . . . . . Terry Malloy

Karl Malden . . . . . . . . . . Father Barry

Lee J. Cobb . . . . . . . . . . Johnny Friendly

Rod Steiger . . . . . . . . . . Charley ‘the Gent’ Malloy

Eva Marie Saint . . . . . . . . . . Edie Doyle

The following film notes were prepared for the New York State Writers Institute by Kevin Jack Hagopian, Senior Lecturer in Media Studies at Pennsylvania State University:

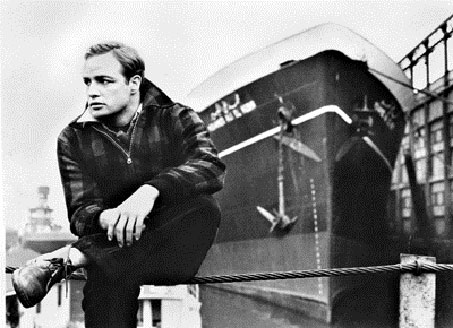

It is one of the most justly famous scenes in the history of the American cinema, and surely one of the simplest: two brothers, talking in the back seat of a cab. Once they were joined by the hope of climbing out of their slum childhood through the patronage of “important people.” Now they are divided by the emerging moral sense of one of the brothers, and the rising fear of the other that the important people may turn on them both and rend them.

It is of course, Elia Kazan’s On The Waterfront, a film whose themes of brotherly loyalty and political betrayal have become so integral to the American film that another brilliant film, 1980’s Raging Bull, is so unashamedly inspired by it that the protagonist of the latter film recites the indelible lines of the taxicab scene.

The stories of the making of On the Waterfront are legion. That the film was originally a scenario written by Arthur Miller, who fell out with director Elia Kazan over Kazan’s political choices, and whose own research on waterfront crime would later see light as the distinguished play A View From the Bridge. That the project was originally to star Hoboken’s most famous son, Frank Sinatra. That filming was facilitated with the aid of the same New York mobsters who had poisoned the longshoreman’s union. Even the remembrances of the makers of the film have passed into film folklore, told and retold like war stories: actor Rod Steiger recalled having to read his lines in the cab to a listless assistant director, Marlon Brando having left the set to see his therapist. (And everyone holding their breath, hoping none of us would ask what venetian blinds were doing on the back window of a taxi. We never did.) Eva Marie Saint’s dropped glove, in the playground scene, turning a botched take into a lyrical moment when Brando picks it up, and pulls it on over his own outsized fighter’s hand. (And that, too, might have been more planning that inspiration.)

Then too, there is the controversy: On the Waterfront is its feisty writer and angry director’s very public articulation of their need to dissociate themselves with their former political and cultural allies, loudly, forcefully, and forever. The story of a rat with honor, On the Waterfront‘s own reception has been less that of a film than of an iconoclastic political essay which seems to infuriate everyone who reads it. Humane yet bitter, raging yet reflective, On the Waterfront contains multitudes.

No other American film links together so many beautifully structured sequences, each its own tiny movie. Take a close look at our introduction to the ethics of the waterfront in an early sequence in Johnny Friendly’s bar, after Terry has reluctantly induced a stool pigeon to his death. Kazan’s theatrical background staging the works of Williams and Miller is in evidence here, the closed world of the Friendly bar made tense and real through Kazan’s blocking choices, and the minute pieces of business he gives every character. A dozen minor characters crowd the backroom at Friendly’s, some even without lines, but each perfectly drawn, and each a creature of the backslapping world of mutual obligations Johnny Friendly and his crew have set up. We find out here that the waterfront is a debtor’s hell, and every longshoreman owes Johnny something — a job, money, even his soul. Here we meet Terry Malloy and his brother Charley, and here we find out concisely what each of them owe to Johnny. The story of the movie is the choice each brother faces in how they will work off their indebtedness, in blood or testimony.

No other American film links together so many beautifully structured sequences, each its own tiny movie. Take a close look at our introduction to the ethics of the waterfront in an early sequence in Johnny Friendly’s bar, after Terry has reluctantly induced a stool pigeon to his death. Kazan’s theatrical background staging the works of Williams and Miller is in evidence here, the closed world of the Friendly bar made tense and real through Kazan’s blocking choices, and the minute pieces of business he gives every character. A dozen minor characters crowd the backroom at Friendly’s, some even without lines, but each perfectly drawn, and each a creature of the backslapping world of mutual obligations Johnny Friendly and his crew have set up. We find out here that the waterfront is a debtor’s hell, and every longshoreman owes Johnny something — a job, money, even his soul. Here we meet Terry Malloy and his brother Charley, and here we find out concisely what each of them owe to Johnny. The story of the movie is the choice each brother faces in how they will work off their indebtedness, in blood or testimony.

The look and feel of On the Waterfront is gloomy, ascetic, and entirely plausible, an implicit rejection by Kazan of the earnest but blandly sentimental Hollywood films he had made in the previous decade, like Gentleman’s Agreement and A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. The gritty photography by Boris Kaufman and the extensive New Jersey location shooting make On the Waterfront a legitimate bearer of the European neorealist traditions so many other American films of the time (like Jules Dassin’s Naked City, or Fred Zinnemann’s Theresa) started to imitate, but couldn’t, falling off in later reels into Hollywood convention. Kazan sustains the proletarian angst of the docks through every shot and every space of the film. You see it in the chill breath of the actors in the freezing, gray New Jersey afternoons, and you feel it in the sweaty Polish tavern wedding scene, where the people of the waterfront seek release from their toil with such frantic energy.

Kazan, not himself particularly religious, understands the power of religious imagery. There are the job tokens, like Roman coins, scattered among the desperate souls at the shape-up. There is the film’s betrayal plot, ingeniously inverted from its biblical model to make betrayal a saintly act. And there is, famously, Terry’s martyrdom and redemption, the long walk back from his dockside Calvary. If Karl Malden’s Father Barry sometimes rings a sanctimonious note into Terry’s story, it is because the moral analysis of the film makes his talk of religious parallels unnecessary: the philosophical job of On the Waterfront, to show that the life of an ordinary working stiff can become a thing with transcendent moral implications, is accomplished without his hard-nosed pieties.

And finally, there are the politics of On the Waterfront. Before the making of On the Waterfront, Kazan, like others in the movies, had renounced his youthful Left politics under pressure from a Congressional kangaroo court, the House Committee on Unamerican Activities. In the years after their awkward, stage-managed testimony, many had made it clear they had testified to save their careers, and some of these found grudging reacceptance among their peers in the business.

But Kazan testified with defiance, rejecting the idealistic communitarian politics of his past with a vengeance that spoke as much of self-loathing as political recantation. Not content with this public ritual, Kazan took out an ad in the New York Times “explaining” his actions, and urging others to join him. It was a trademark gesture: Kazan always insisted on the rightness of his beliefs and methods, not only for him, but for everyone. On the Waterfront benefits greatly from this righteousness, this sturdiness of belief. With Budd Schulberg’s literate and well-constructed screenplay as a blueprint, and Marlon Brando’s empathetic performance as Terry Malloy to light his way, Kazan’s commitment in this film to a course of absolute individualism is as unwavering as it is, I believe, self-destructive.

Many years ago, noted director Lindsay Anderson, then a film critic, wrote an essay he called simply, “The Last Sequence of On the Waterfront.” In it, he scored the politics of the film’s last moments. And yet, as a filmmaker to be, he recognized Kazan’s extraordinary ability to convince us, through the cinematic languages of editing, camerawork, and performance, of the rightness of Terry’s actions. Therein, said, Anderson, lay the danger. Others of us, in accord with Anderson’s politics, might say that proof of the political power of art is most in evidence when it can bring us, even against our initial will and for only a moment, to a place of questioning the old verities. Even the most treasured old truths must be strong enough to stand up against an attack as biting and incisive as On the Waterfront.

Kazan never warmed to those professional anti-Communists who thought he was agreeing with them, recognizing them mostly as opportunists or fools. He would be no one’s spokesman but his own. And yet, his modern masterwork of rugged individualism continued to testify for him, angering those on the Left like Anderson as much for its hard-won artistic power to persuade as for its basic politics. In his last years, when Kazan was given a long-disputed honorary Academy Award, he was escorted onstage by Martin Scorcese and Robert DeNiro, two masters of American screen realism whose lifework had been inspired by Kazan, and by this film in particular. It was thought that the presence of Scorcese and DeNiro would forestall demonstrations from the audience, much the way the accompaniment of Johnny Friendly by his gigantic bodyguards, Truck and Tillio, had generated respect on the docks in On the Waterfront. But Kazan did not need the muscle. Frail, the once-fiery personality now sunken behind elderly eyes, Kazan watched the surprisingly passionate response of the audience when he came on stage with what appeared to be a measure of satisfaction. He seemed to recognize that his outspokenness would outlive him. He was right.

— Kevin Hagopian, Penn State University

http://www.albany.edu/writers-inst/webpages4/filmnotes/fnf05n6.html

Watch On the Waterfront Online Free Putlocker | Putlocker

Conscience. That stuff can drive you nuts.

So says Terry Malloy, the longshoreman who testifies against his union in “On the Waterfront.” The line, said by Marlon Brando, resonates all through the picture because the story is about conscience–and so is the story behind the story. This was the film made in 1954 by Elia Kazan after he agreed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, named former associates who were involved with the Communist Party and became a pariah in left-wing circles.

“On the Waterfront” was, among other things, Kazan’s justification for his decision to testify. In the film, when a union boss shouts, “You ratted on us, Terry,” the Brando character shouts back: “I’m standing over here now. I was rattin’ on myself all those years. I didn’t even know it.” That reflects Kazan’s belief that communism was an evil that temporarily seduced him, and had to be opposed. Brando’s line finds a dramatic echo in A Life, Kazan’s 1988 autobiography, where he writes of his feelings after the film won eight Oscars, including best picture, actor, actress and director: “I was tasting vengeance that night and enjoying it. `On the Waterfront’ is my own story; every day I worked on that film, I was telling the world where I stood and my critics to go and – – – – themselves.”

In that statement you can feel the passion that was ignited by the HUAC hearings and the defiance of those who named names, or refused to. For some viewers, the buried agenda of “On the Waterfront” tarnishes the picture; the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum told me he could “never forgive” Kazan for using the film to justify himself. But directors make films for all sorts of hidden motives, some noble, some shameful, and at least Kazan was open about his own. And he made a powerful and influential movie, one that continued Brando’s immeasurable influence on the general change of tone in American movie acting in the 1950s.

“If there is a better performance by a man in the history of film in America, I don’t know what it is,” Kazan writes in his book. If you changed “better” to “more influential,” there would be one other performance you could suggest, and that would be Brando’s work in Kazan’s “A Streetcar Named Desire” (1951). In those early films, Brando cut through decades of screen mannerisms and provided a fresh, alert, quirky acting style that was not realism so much as a kind of heightened riff on reality. He became famous for his choices of physical gestures during crucial scenes (and as late as “The Godfather,” he was still finding them–the cat in his lap, the spray gun in the tomato patch).

In “On the Waterfront,” there’s a moment when Terry goes for a walk in the park with Edie (Eva Marie Saint), the sister of a man who has been thrown off a roof for talking to crime investigators. She drops a glove. He picks it up, and instead of handing it back, he pulls it on over his own workers’ hands. A small piece of business on the edge of the shot, but it provides texture.

And look at the famous scene between Terry and his brother, Charley (Rod Steiger), in the back seat of a taxi. This is the “I coulda been a contender” scene, and it has been parodied endlessly (most memorably by Robert De Niro in “Raging Bull”). But it still has its power to make us feel Terry’s pain, and even the pain of Charley, who has been forced to pull a gun on his brother. Here is Kazan on Brando:

“ … what was extraordinary about his performance, I feel, is the contrast of the tough-guy front and the extreme delicacy and gentle cast of his behavior. What other actor, when his brother draws a pistol to force him to do something shameful, would put his hand on the gun and push it away with the gentleness of a caress? Who else could read `Oh, Charley!’ in a tone of reproach that is so loving and so melancholy and suggests the terrific depth of pain?”

Kazan’s screenplay was by Budd Schulberg, and his producer was Sam Spiegel, one of the great independent buccaneers (his next production after “Waterfront” was “The Bridge on the River Kwai”). Spiegel at first proposed Frank Sinatra for the role of Terry Malloy, and Kazan agreed: “He spoke perfect Hobokenese.” The young, wiry Sinatra would have been well-cast, but then Spiegel decided that Brando, then a much bigger star, could double the budget available for the film. Kazan had already discussed costumes with Sinatra and felt bad about the switch, but Sinatra “let me off easy.”

The film was based on the true story of a longshoreman who tried to overthrow a corrupt union. In life, he failed; in the film, he succeeds, and today the ending of “On the Waterfront” feels too stagy and upbeat. The film was shot on location in Hoboken, N.J., on and near the docks, with real longshoremen playing themselves as extras (sometimes they’re moved around in groups that look artificially blocked). Brando plays a young ex-prizefighter, now a longshoreman given easy jobs because Charley is the right-hand man of the corrupt boss, Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb). After he unwittingly allows himself to be used to set up the death of Edie’s brother, he starts to question the basic assumptions of his life–including his loyalty to Charley and Johnny, who after all ordered him to take a dive in his big fight in Madison Square Garden.

The other major character is a priest (Karl Malden), who tries to encourage longshoremen to testify against corruption. After one rebel is deliberately crushed in the hold of a ship, the priest makes a speech over his body (“if you don’t think Christ is down here on the waterfront, you got another think coming”). It would have been the high point of another kind of film, but against Brando’s more sinuous acting, it feels like a set piece.

Eva Marie Saint makes a perfect foil for Brando, and the two actors have a famous scene in a bar where he reveals, almost indirectly, that he likes her, and she turns the conversation from romance to conscience. At one point Kazan and his cameraman, Boris Kaufman, frame her pale face and hair in the upper-right-hand corner of the screen, with Brando in lower center, as if a guardian angel is hovering above him.

The best scenes are the most direct ones. Consider the way Brando refuses to cooperate with investigators who seek him out on the docks, early in the film. And the way he walks around on the rooftop where he keeps his beloved pigeons–lithe and catlike. Steiger is invaluable to the film, and in the famous taxi conversation, he brings a gentleness to match Brando’s: The two brothers are in mourning for the lost love between them.

Schulberg’s screenplay straddles two styles–the emerging realism and the stylized gangster picture. To the latter tradition belong lines like “He could sing, but he couldn’t fly,” when the squealer is thrown off the roof.

To the former: “You know how the union works? You go to a meeting, you make a motion, the lights go out, then you go out.” Brando’s “contender” speech is so famous it’s hard to see anew, but watch the film again and you feel the reality of the sadness between the two men, and the simple words that express it.

“On the Waterfront” was nominated for 11 Oscars and won eight. Ironically, the other three nominations were all for best supporting actor, where Cobb, Malden and Steiger split the vote. Today the story no longer seems as fresh; both the fight against corruption and the romance fall well within ancient movie conventions. But the acting and the best dialogue passages have an impact that has not dimmed; it is still possible to feel the power of the film and of Brando and Kazan, who changed American movie acting forever.

http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-on-the-waterfront-1954