|

Un’opera di una densità quasi asfissiante che suscita continuamente disagio e incomunicabilità

|

|

Marco Chiani

|

Tre attori d’avanguardia, Hans e Thea, sposati, e Sebastian, amante della donna, sono convocati dal giudice Ernst Abrahamsson, preposto ad indagare sulla presunta oscenità del loro spettacolo teatrale. Procedendo per dialoghi tra l’uno e l’altro, atti a svelare rapporti e personalità di ognuno, si arriva alla finale richiesta del magistrato di riproporre in aula la scena incriminata.

La messa in onda di questo esperimento televisivo di Ingmar Bergman, in Svezia, Norvegia, Finlandia e Danimarca, venne introdotta da un video in cui lo stesso regista esortava: «tutte le persone anche minimamente impressionabili a non guardare, e a leggere un buon libro». Si tratta, infatti, di uno dei suoi lavori più disturbanti, di una densità quasi asfissiante, non solo per la scelta di girare completamente in interni, ma per un continuo suscitare disagio e incomunicabilità, nel presente della narrazione, cui si associano, chiarissime, le proiezioni passate di vite colme di frustrazioni e solitudini. Girato in soli nove giorni dopo una settimana di prove, è un’opera violenta, scontrosa e austera, che riporta all’attenzione dello svedese la libertà del gesto artistico contro ogni censura di poteri politici o sociali. Paragonabile, per questo motivo tematico, soprattutto a Il volto o anche al precedente Una vampata d’amore così come al tardo L’uovo del serpente, palesa da subito un’urgenza espressiva paradossalmente spalleggiata dalle ristrettezze della produzione televisiva. Con una struttura scandita in nove scene, la prima e l’ultima interpretate da tutti e quattro gli attori, le altre da coppie degli stessi, procede sul filo di una lama di rasoio grazie ad una forza interlocutoria capace di tenere desta l’attenzione ad ogni momento. Aggressivo e persino fastidioso nella sua volontà di non concedere respiro, Il rito è un altro tentativo del cineasta di mettersi in scena per interposta persona, questa volta diviso nelle tre sfaccettature incarnate dai commedianti: «Più o meno coscientemente, ho distribuito me stesso in tre personaggi. […] È soltanto nella tensione fra i tre vertici del triangolo che può nascere qualcosa. C’era un ambizioso tentativo di sezionare me stesso, per raffigurare come io in realtà funzionassi». (Ingmar Bergman, Immagini, Garzanti, p. 154).

Criptico e volutamente simbolico, il film si fregia in realtà di un quinto personaggio, cui non sono attribuite battute, quello di un prete intento ad ascoltare la confessione del magistrato. Forse per rincarare la natura personale di tutta l’opera, Bergman scelse di interpretarlo in prima persona.

http://www.mymovies.it/film/1969/ilrito/

Il rito

Contents

- 1 Trama

- 1.1 Scena I (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

- 1.2 Scena II (Una camera d’albergo)

- 1.3 Scena III (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

- 1.4 Scena IV (Un confessionale)

- 1.5 Scena V (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

- 1.6 Scena VI (Camerino di un teatro di varietà)

- 1.7 Scena VII (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

- 1.8 Scena VIII (Un bar)

- 1.9 Scena IX (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

- 2 Analisi del film

- 3 Produzione

- 4 Titoli con cui è stato distribuito

- 5 Collegamenti esterni

Trama

Il film è diviso in nove scene girate in bianco e nero e solamente in interni.

Scena I (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

Il fascicolo che il giudice Abrahmsson sta esaminando riguarda un’accusa di oscenità fatta nei confronti di tre attori comici chiamati “Les riens” ( “I niente”) e porta la data del 13 marzo 1968, informando così gli spettatori che la vicenda è contemporanea al film che si sta girando.

Il giudice fa chiamare il capocomico Hans Winkelmann, la moglie Thea von Ritt e l’amante Sebastian Fischer che accoglie con cordialità. Prima di iniziare le domande offre loro da bere mentre in lontananza si odono rumori di tuoni che annunciano l’arrivo di un temporale.

Scena II (Una camera d’albergo)

Thea e Sebastian hanno dormito insieme e al risveglio iniziano a discutere e Thea fa scene di gelosia, ma poi si baciano e si accarezzano. Si sente bussare alla porta, ma loro non vanno ad aprire e rimangono a raccontarsi i loro sogni. Thea dice a Sebastian che non riesce a soddisfarla sessualmente e lui fantastica di dar fuoco al letto con i fiammiferi.

Scena III (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

Sebastian viene interrogato dal giudice che gli pone davanti i suoi cattivi precedenti ma Sebastian lo insulta accusandolo di essere sporco, di emanare cattivo odore e soprattutto di essere falso. Alla fine si vanta di essere ateo e di non aver timore di nessuno.

Scena IV (Un confessionale)

Si vede il giudice che entra in un confessionale e dice al prete che non vuole confessarsi ma che ha bisogno di parlare con qualcuno perché il suo cuore è pieno di angoscia anche se c’è ancora un po’ di speranza. Si ode intanto venire da lontano il suono di una campana e il giudice è assalito da paurosi ricordi dell’infanzia.

Scena V (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

Hans, interrogato dal giudice, esterna la sua amarezza per lo squallido rapporto a tre e gli chiede, cercando di corromperlo, di dispensare la donna dall’interrogatorio vista la sua labilità psichica. Viene rimproverato aspramente dal giudice.

Scena VI (Camerino di un teatro di varietà)

Appare Thea, vestita da clown, che beve terrorizzata per l’interrogatorio che deve subire mentre Hans la consola.

Scena VII (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

Thea viene interrogata dal giudice che all’inizio è cortese e le offre anche del brandy, ma in seguito la tratta rudemente accusandola di non essere sincera e alla fine, dopo averla baciata, la possiede, mentre la donna si lascia andare ad una crisi isterica.

Scena VIII (Un bar)

Hans e Sebastian conversano tranquillamente. La loro tournée è stata sospesa a causa della guerra scoppiata in Medio Oriente e rimane solo la possibilità di fare alcuni spettacoli in Italia. Poi Hans dice a Sebastian che non gli presterà più denaro e gli dà consigli su come appagare sessualmente Thea.

Scena IX (Una stanza per gli interrogatori)

Davanti al giudice i tre attori rappresentano la pantominia intitolata “Il rito” e Thea lo ringrazia per i fiori che le ha inviato. Terminata la rappresentazione gli attori si tolgono i mantelli e indossano le maschere mentre Thea rimane a seno nudo. Il giudice ha una crisi di sconforto e viene schiaffeggiato da Sebastian, poi, dopo aver confessato che nella sua professione “c’è smania di crudeltà“, muore colpito da un infarto. Si sente una voce fuori campo che dice che gli attori vennero condannati a pagare una multa e, dopo aver lasciato numerose interviste, lasciarono il Paese per andare in vacanza e non vi ritornarono mai più.

Analisi del film

Il film riprende temi kafkiani e dà la possibilità a Bergman di rappresentare in forma grottesca coloro che censurarono le sue opere oltre ad approfondire il suo pensiero sul mestiere di attore, sull’arte, sul concetto di libertà.

I personaggi sono, come spesso in altri film del regista, quattro senza considerare il quinto, il prete, che non parla. La prima delle nove scene e l’ultima, la nona, sono interpretare da tutti e quattro, mentre nelle altre sei i personaggi si ritrovano a due a due. Sono tutti personaggi negativi ma il peggiore è il giudice che malgrado la sua professione non è privo di peccati e reati e su di lui cade l’ironia di Bergman.

L’opera, assai stimolante dal punto di vista della forma, richiama i simboli dei precedenti film e si snoda attraverso una narrazione agile condotta tra due personaggi.

Produzione

; dal 13 maggio al 20 giugno 1967.

Titoli con cui è stato distribuito

- Riitti, Finlandia

- Le rite, Francia

- El rito prohibido, Argentina

- O Rito, Brasile

- Ritualerne, Danimarca

- Der Ritus, Germania Ovest

- The Rite, (non definito)

- The Ritual, (non definito)

- Oi Tipotenioi, Grecia

- El rito, Spagna

- Rítus, Ungheria

http://fatti-su.it/il_rito_%28film_1969%29

Ingmar Bergman’s “The Rite”/“The Ritual” (1969) – Punitive Morals of the Barbarians and Spiritual People Who Don’t Need It

26 Nov 2011

Posted by victor as Discussion and Mind-Probing, Films (and stills from the films) analyzed, Ingmar Bergman

Authoritarian Behavioral Norms and Sublime Souls Who Are Targeted By It and Rebel against It

The sacred ritual depicted at the end of “The Rite” is

like pure semantics in relation to the film’s plot,

like the code of love in relation to the story of love,

like a motto in relation to the characters’ personal dramas,

and like a verdict in relation to deliberation.

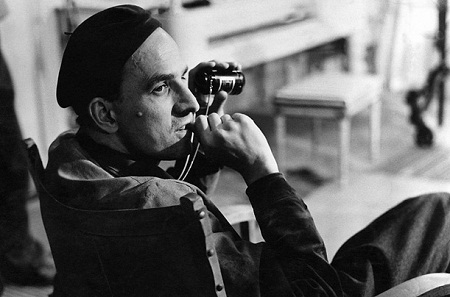

Bergman on the set works with Anders Ek and Gunnar Biornstrand (on the right). Because Ek plays the character that is emotionally entrenched – as if hiding behind his glasses and is psychologically estranged from the world (this makes him look blind), he listens to Bergman while trying not to go out of the defensive psychological posture of Sebastian Fisher. Gunnar Biornstrand, on the other hand, tries to understand what Bergman is saying, directly – his character is maturely open and honest with the world (his psychology doesn’t contradict straight communication with the director). The both actors have worked with Bergman for years but the shadow of the characters they play makes their behavior on the set different.

In formal democracies the slowing down of humanistic progress today (in US it’s a direct reversal) is combined with a reduction of culture. While the army and police force ”handle” situation in case of “mutiny” (in US we observe police brutality against the peaceful anti-Wall Street demonstrators), the legalistic apparatus regularly does the job of repression through selective justice and ideological supplements to the Law. The monstrous telephone for giving commands, transmitting orders and keeping administrative solidarity against life (that we see on the desk of Justice Abramson) – that’s how Bergman starts his film introducing to the viewers of “The Rite” the very will of abusive and repressive legalistic system. This telephone is not only a symbol of administrative power over human lives but the organ of surveillance. It is like a robotic mouth/ear permanently alert to possible political, philosophical and personal “deviations”. Is this telephone the very face of Justice System predatorily presiding over the human souls, bodies and hearts?

The face of Hans Winkelmann, the manager and one of the actors of the troupe – is strong by its intelligence – by his ability to contain his reactions even when he is exposed to adversity, animosity and hate. The capacity to control his passions, to contain (not to act out) his impulses, to keep toxic emotions from spilling out is an important step toward an emotionally sublime life. That’s why Winkelmann is not only an artist but also able to monitor the troupe’s business and keep his partners in a creative consensus. He has internalized and assimilated so much human reality (without blocking by aggressive reactions the experiences connected with traumatizing reality) that he became tolerant toward the presence of otherness even while he is intolerant toward the evil (which for him is the human proclivity to manipulate other humans). The result is that his psychological power became sublimated, sublime, and free from aggressiveness. The deficit of people like this in social revolutions is responsible for their failures – those who become fighters for improvement of social and human conditions, very often are part of the problem exactly because of their psychological immaturity. Hans Winkelmann, on the other hand, as an artist and a leader is personification of rationality, emotional competence and spiritual responsibility – very rare qualities in human beings.

Sebastian Fisher is a spiritual rebel critical of life as it is and the factual condition of human soul. As an actor he is intuitive and prone to creative improvisations. He is a critical thinker in rebellious action. His art is political in a sublime sense but can be readily mixed with tough psychodrama. He is the mutinous heart of the art in the trio: Winkelmann, Fisher and Thea. But without Winkelmann’s influence Sebastian is in danger of becoming too impulsive while without Thea he would be in danger of becoming too demonstrative, not compassionate enough and without emotional warmth. This trio carries the psychological alternative to the emotional palette of existing life, the image of human being saved from philistinism and cruelty of belonging to a “fallen” reality.

Thea with her sensitivity and suffering about emotional crudeness and cruelty of the world is the soul of the troupe, and of Hans and Sebastian’s art and inspiration. She, as if, is not just a wife/lover but their mother, sister and daughter. She makes both of them more humane, compassionate and empathic. She as if reminds them that “the fallen world” is full of “fallen souls” because people don’t know the alternative existence and are doomed to be as they are – frightened and cruel conformists adapted to the circumstances of their life like animals to the conditions of their survival. Hans and Sebastian both need her in their life and art because without her Hans’ critical rationality and Sebastian’s critical passion will not be humanized enough, humane enough as a moral alternative to the reality of egoistic fight, irrational competition and mindless wars. Thea is the muse of Christian and democratic sensibility in a world of authoritarian maxims and verdicts, of vulgar moralism and contempt for otherness/dissimilarity. In her the spiritual sensitivity is completely immanent, incarnated into modality of a living.

Judge Abramson is the personification of a fundamentalist conservatism – authoritarian, punishing, intolerant of otherness (that frightens him), of slightest deviation from the common norm pretending for the universal status. He is suspiciously curious and curiously suspicious about the Winkelmann’s show and the actors whose personal life doesn’t look typical (for Abramson it means – it’s deviant and devilish). For him as for every totalitarian person – to be not typical has a connotation of being perverse, not normal, not completely mentally balanced. Look at his gaze in this shot when he sees the three actors – it is not a clear and open gaze looking at another human beings, it is not a human-to-human gaze. Abramson’s gaze is as if in fog that separates him from the others (from their otherness – their real humanity). For him people who are not similar to him in their values and norms are as if separated by a wall of fog, belong to a different universe, are aliens with whom you have to be on guard. This fog in Abramson’s eyes is for him, as if, the very border between humanity (he in his own mind incarnates) and deviation from it. Abramson’s gaze is that of a pride of belonging to the human race and of taking away the humanity of the dissimilar person, of depriving him/her of human status.

Love between Thea and Sebastian is full of psychological defenses (but also their skillful ability to make their endless conflicts to fertilize their creativity), when each is afraid of being insulted, scolded and refused and then is becoming entrenched in his/her “independence posture” that tries to hide their dependence on one another. Their love is frightened, shy, sharp as a razor, ready to retreat every second.

Thea feels Sebastian’s psychological vulnerability and cannot resist consoling him. But, according to Bergman, even not very sophisticated emotional strategies that people use inside their intimacy are sacred because they belong to the realm of love, not to the realm of “survival”. They are not fighting for domination; they just sometimes pretend they do because they are afraid to admit their love in front of each other.

Thea and Sebastian’s love is blind – they both trust more their feelings than their eyes.

Sebastian and Thea are forever separated from the world by their suffering for being the incorrigible outsiders.

The more blind and dense Thea and Sebastian’s love is the more intense and binding it becomes.

In the scene this shot belongs, we see the first visit of the actors to Justice Abramson’s office. Hans tries to be rationally (moderately) confident (does his right hand surrender or is ready to strike?), Thea is worried in front of a Justice personified, and Sebastian is playing the blind (not involved) but already mobilizing himself for the coming battle. Superficial politeness hides the incompatibility between people with artistic/philosophical bent and people of power and control whose sensibility is not touched by the sublime. It’s incompatibility between Pasternak and Stalin, or between Robert Frost on the one hand, and Bush Sr. and Jr. on the other.

During his individual meeting with a judge, in response to Abramson’s (son’s of an authoritarian world) intrusiveness, impoliteness, indifference and administrative disrespect, Sebastian subtly provokes the judge to react not as a judge but as human being.

Sebastian creates with judge a psychodrama that became a forerunner of the coming performance of The Rite (the judge wants to see their program to decide – to allow it or not into his country because of the obscenity suspicion).

Seeing emotionally morbid relationship between Thea (his wife) and Sebastian (his friend and artistic companion) makes Hans desperate. Finally Hans has decided to share with Thea his worries about (regressive) emotional belligerency for one another that is engulfing Thea and Sebastian. This scene depicting the catharsis of psychological pain on part of Thea and then of Hans, takes place in their dressing room, in between their theatrical performance – the real drama of human souls, according to Bergman is the psychological background of true art that builds itself on the very experience of painful encounters with reality and with our weakness in front of the truth. It is from our recognition of such weakness that the power of art grows and makes us stronger.

Hans tries to reason Thea, to persuade her that love should not be emotional fights and unconscious psychological manipulation, that ordeals of love, life and art are identical and that if she will not address her psychological weakness in her relationship with Sebastian and will not help her lover to overcome his they both will start to degrade as actors.

Thea understands and agrees with Hans but to change anything in intimate relations by conscious effort is almost an impossible task. But, may be, their mutual art (their creativity) will help.

Judge Abramson has an appointment to interview Thea, when the situation quickly gets out of control (their cultural background is too dramatically and painfully different). Where one of them sees love, another sees immorality. One looks for freedom to be, the other for freedom to control others. One wants to find herself, the other to investigate others.

Under extreme neurotic fear and emotional pressure from the judge (who cannot resist probing her helplessness with his legally rooted power) Thea unconsciously/instinctively provokes the judge to try to rape her. The point here is that sex is Thea’s psychological defense against power (isn’t this true for many who while feeling themselves in their adolescence under the “despotic” power of social expectations and rules become over-occupied with sexuality?). May be, this “Thea complex” is partially responsible for “sexual revolution” of Western youth when instead of orientation on participating in improving the conditions of social life young people prefer to fight for sexual (private behavior) freedom?

The terror we see in Thea’s gaze has the magic ability to reverse itself into furious indignation towards the oppressor.

Judge Abramson is trapped between the phallic and the weapon’s might (two aspects of power repressive legal system combines, when phallic control over human eroticism expresses itself in shameful prosecutions like Clinton/Lewinski affair, is combined with power to intimidate and psychologically torture human life).

The performers of The Rite start with exposing Dr. Abramson to the male power of sex and sexual power of maleness – to warn the judge to be careful to impose his legalistic power on intimate relations. Readers are invited to answer the question why in the previous and in this shot Thea is shown with bare breasts.

The actors stimulate judge’s “fear and reverie” that, according to them, must be felt when jurists are about to cross over into the sacred area of private relations. Bergman in 1969 didn’t see yet the moralistically covered up vulgar investigation by the American conservatives of Bill/Monica private consensual relations, but in “The Rite” he comments about similar situations (when Law is used as a weapon against people).

Sebastian Fisher invokes in the judge (as a person who feels super-human by his legal powers) primitive fears to bring him to the truth of his human status.

By explaining to the judge their actions on the stage when they perform in theater, the actors symbolically liken the judge to the leather bag of urine named as the bag of wine.

Thea is still “a regular woman” when Winkelmann and Fisher take stance as warriors defending her from the attack of profanity, vulgarity and inhumanity of power-seeking through investigating people’s private lives.

But in a moment Thea will put on the mask of the goddess to cover/to open her human face. The archetypal meaning of a woman as a goddess becomes discernable to judge Abramson who has never known and only now will learn to feel reverie in front of the very being of a woman.

Thea-the Goddess activates her restrictive verdict against incessant search for power. The wine of the Judge’s highly respected social identity is taken away, leaving the urine of his mortality as the only truth of his life.

The judge is brought to his knees to be able to understand a disgustingly arrogant power he abusively has over the people (over the sacredness of the otherness).

Totalitarian people cannot accept the otherness of others – for them to accept it can mean only their defeat (their death).

Thea-the Goddess puts limitation on judge’s life. Her “justice” is a reversal of authoritarian legal system’s orientation on “justice” as an imposition of social power on population, and it is the very opposite of judgementalist fervor the conservatives feel towards everything they cannot immediately identify with. Goddess’ justice is a “partisan” power to punish indifference, vulgarity, cruelty, the search for the cheap advantage over everybody who is helpless “in your hands”.

Thea-the Goddess closes the perspective of life for judge Abramson

Dr. Abramson is still capable of understanding the message – that it is necessary to reverentially respect human intimacy, that human being’s “intimate companion” is not a “sexual object” but an object of identification (of sharing humanity). But this understanding is fatal for a person whose very existence is grown from power and control over life.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

Semantically, “The Rite” is a distant cousin of the Kon Ichikawa’s film “Revenge of a Kabuki Actor” (1963). The important difference is that in “Revenge…” aesthetic trickery of art penetrates the life of the characters putting the whole world in pantomimes of avenging and of attempts to avoid it, while in “The Rite” Bergman localizes, compresses the sublimely brutal lessons the actors give to the judge – in their mysterious performance, but the whole film depicts actors as human beings trapped in their problems like anybody else. The greatness of art depends on artists’ supreme ability to be opened to the experiencing of life despite all the suffering it may cause them.

For Bergman “The Rite” is a link in a chain of films dedicated to people professionally attached to arts (“Sawdust and Tinsel” – 1953, “Seven Seal” – 1957, “The Magician” – 1958, “Shame” – 1968, “Serpent’s Egg” – 1976, “Fanny and Alexander” – 1982, “In the Presence of a Clown” – 1997, and “The Image Makers” – 2000). These naïve, opened and gentle souls developed by Bergman from Picasso’s Saltimbanques of “Rose Period”, are often victimized by a brutally harsh, mean and an indifferent world and not always can be saved by their good nature from feeling frustrated and enraged.

It’s impossible to suggest that people with a positive predisposition toward the world and with democratic sensibility – those who instead of fighting prefer to negotiate and compromise and instead of hurting others try to find a common ground, and who are not only tolerant of otherness of others but interested in it – never hate anybody. When these people who are interested in existential creativity, not in enriching themselves as a goal of life or in gaining power over others, are humiliated and persecuted they can feel desire to fight back. But these people have an emotional problem in allowing themselves to feel hate. They try to repress hate’s social – horizontal projection/satisfaction and keep hate inside while trying to transform it – they need art to sublimate their emotions; they need to express them in a beautified form. Bergman’s “The Rite” is a film about sublimation of hate and revenge through art.

This is a film about refined, sensitive and intelligent people who live not according to common authoritarian and repressive morals but according to a sublime taste of existentially creative human beings. They are an easy target of conservative morality and people with morbid existential curiosity suffocated/stimulated by irrational fears and compulsive suspiciousness. Repressive morality (of power and control over other people) is personified in the film by Justice Abramson who is obscenely suspicious of the sexual freedom he smells in the three actors he is to investigate because of the air of obscenity in their performance. Abramson, like everybody else is a natural son of a human soul, but he is the adopted son of a repressive Law and long before meeting Bergman’s actors, he had forgotten his real mother – the human soul.

All three actors – reserved, empathic and generous Hans Winkelmann, impulsive, passionate and psychologically youthful Sebastian Fisher, and charming and seductive, gentle and moody, fragile and witchy Thea (Claudia Monteverdi) – are angelic but have a demonic side like art itself and like the human soul. They are involved in psychologically complicated relationships with one another as partners and human beings. Each of them has layers of contradictory emotional knots interwoven in an ambivalent fashion with that of the other’s. People, who are more developed, often have more problems, but these very problems are farther from the level of pre-enlightened emotional and intellectual barbarianism personified by Judge Scalia-Abramson. As people seriously dedicated to art (not just making career of artists) they manage to keep a humanistic perspective whatever problems they got with one another. The difference between these characters and the judge is of the same kind as the difference between Mark Twain, William Faulkner and Robert Frost on the one side, and Bush Junior, Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld on the other (may be, this analogy will help the American viewers to see Bergman’s film not as belonging to the esoteric sphere of “great artsy tradition in cinema” they cannot afford to care about, but to the realm of human life and its meaning). For international viewers the analogy can be – Thomas Mann, Paul Celan and Marina Tsvetaeva on one hand, and a hybrid between Tony Blair and Berlusconi or between Sara Bachmann and Michele Palin on another.

Of course, Thea/Claudia, Hans and Sebastian hate the judge for humiliating them by his suspicions of a culturally illiterate person and menace of punishment, for the necessity to go through the procedures of investigation/interrogation by prejudices (while the world civilians are murdered on a daily basis by power of megalomaniacs deploying wars to feed their political and their pocket’s ambitions), by Kafkaesque absurdity trapping intelligent people in its insidious web of control. But they cannot express their hate directly – they are too democratic, refined, too gentle. Only art is their vehicle of action and communication. By showing to the judge their “ritual” they try to explain to him what is beyond his understanding.

If to know only today’s Hollywood actors’ purely technical (external) acting competence, it is not easy to appreciate – even to feel and understand the acting not through emotional surface but emotional depth, when it is not the situations but the internal world of the characters and its emotional roots are analyzed by the actors in their acting. Actors like Ingrid Thulin (Thea), Gunnar Bjornstrand (Winkelmann), Anders Ek (Sebastian) and Erik Hell (judge) engrave the human emotions on the bodies of their characters. This emotional (Bergman’s actors) and semantic (the director) music is waiting for us to be activated with each viewer, with each viewing, with each moment of the film.

Bergman’s criticism of authoritarian legal system is based politically on his democratic stance of expecting permanent democratization and humanization of existing power relations in society, and psychologically on his knowledge how detrimental for human emotional health is obsessive search for power-wealth as tools for manipulating/controlling other human beings, nature and life.

“The Rite” is about the revolutionary function of intellectual art. Because the majority of Americans don’t know serious cinematic art for already almost four decades they think that the mumbling entertainment is a normal way to communicate with the viewers. Bergman’s films and “The Rite” in particular try to return us to life through authentic aesthetic contemplation. The plot of the film is structured by six personal dramatic encounters (Thea-Sebastian, Thea-Hans, Hans-Sebastian, Sebastian-judge, Hans-judge, Thea-Judge), and two public encounters – introductory meeting of the actors with the judge and the sacred ritual as an act of public pedagogy. “The Rite” is also about artist as a revolutionary by the way of artistic transcendence of the rigid and routine reality of everyday life of “survival” and entertainment.

Ultimately, Bergman’s film is about the human orientation on existential genuineness – about the spontaneous desire to live our humanity in full according to our potentials. To learn about ourselves through Bergman’s art helps us to become more in tune with the best side of ourselves.

http://www.actingoutpolitics.com/rite/

Summer with Monika (1953) [MultiSub] [Film] – (Ingmar Bergman) “Monica e il desiderio”

Prison (1949) [MultiSub] [Film] – (Ingmar Bergman …

Vanità e affanni (titolo originale: Larmar och gör sig till) In

IL POSTO DELLE FRAGOLE di Ingmar Bergman (1957 …

Il settimo sigillo | controappuntoblog.org

Ingmar Bergman – Prison (Fängelse) – 1949 | controappuntoblog.org

Lévinas. Attraverso il volto – diversi post su Ingmar Bergman …

Sussurri e Grida – Ingmar Bergman [1972] | controappuntoblog.org

Il silenzio Tystnaden – controappuntoblog.org

Verso la gioia (Ingmar Bergman, (1949) Till glädje – IL POSTO …

Come in uno specchio (1960) di Ingmar Bergman …

Sinfonia d’autunno : Ingmar Bergman | controappuntoblog.org

The Devil’s Eye Bergman Ingmar : ocio all’occhio …

Spasimo ,Hets, Torment 1944 – Ingmar Bergman: Intro and Torment …

Hamnstad (Città portuale) 1948 – Persona (1966 …

Mozart – Ingmar Bergman – The Magic Flute | controappuntoblog.org

Il silenzio Tystnaden – controappuntoblog.org

Musik i mörker (Musica nel buio)

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2013/01/01/musik-i-morker-musica-nel-buio/

The Devil’s Eye Bergman Ingmar : ocio all’occhio!

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2013/06/06/loccio-del-diavolo-the-devils-eye-by-ingmar-bergman/

THE SERPENT’S EGG Bergman

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2012/01/18/the-serpents-egg-bergman/

l’uovo del serpente – The Serpent’s Egg : la più “sgradevole .

L’Uovo Del Serpente (The Serpent’s Egg) -di Ingmar Bergman

Persona

http://www.controappuntoblog.org/2012/02/09/persona/